In China, Finland and New Jersey, students experiment with microbes, chemicals and culture

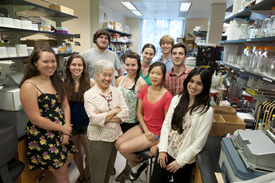

This summer, nine undergraduates stationed at different corners of the globe collected soil and sediment from the bottoms of creeks and rivers, spiked the samples with toxic organic compounds and observed the results.

The students, including two from Rutgers, spent 10 weeks working in China, Finland and New Jersey. Their mission: to compare the ability of different microorganisms found in the environment to degrade harmful chemicals, such as PCBs and BFRs (brominated flame retardants), an important class of emerging global contaminants.

The program, administered by the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences (SEBS) and funded by a three-year, $375-000 grant from National Science Foundation, is called Biotransformation in the Tropics, Temperate and Sub-arctic Environments (BITTSE) – one of a number of projects the NSF funds at various location for undergraduate students.

The scientific question BITTSE students were trying to answer is this: If you take sediment out of river and creek bottoms in the sub-Arctic (Finland), the temperate zone (NJ) and the tropics (China), and add chlorinated or brominated organic compounds known to be environmentally dangerous, what happens? Do different microbes in these different places degrade the compounds differently?

The question is scientifically interesting but also socially important, according to Lily Young, the dean of international programs and research at SEBS who brought the NSF-REU (Research Experience for Undergraduates) project to Rutgers.

“Rivers don’t stop at borders,” said Young, who is also a professor of environmental biology at SEBS. “Air pollution doesn’t stop at political boundaries. So, if we’re to understand how the environment works, how it’s damaged and what to do about it, we have to work internationally.”

The NSF-REU scholars, who receive a $5,000 stipend, travel expenses and academic credit, met at Rutgers at the start of the program to formulate their approach and participated in videoconferences throughout the summer. During the first week of August, they reconvened at SEBS for a weeklong symposium to discuss their experiences, compare results and develop a set of conclusions regarding the role of biogeography in metabolizing new organic pollutants.

Young said the program not only gives students hands-on research experience in solving an important environmental problem it also teaches them collaborative investigative and communications skills – and Rutgers benefits as well.

“This extends the Rutgers brand overseas,” Young said. “In particular, it strengthens our ties with the University of Helsinki and the South China University of Technology, our partners. It also raises Rutgers' profile among top undergraduates in this country, since it’s highly competitive. And, finally, it serves as a recruiting tool for strong applicants to our graduate programs.”

In addition to scientific investigation, students also had the opportunity to answer this question: Is this what I want to do with my life?

For Rutgers’ Finerty Hu, a Bergen County native who spent the summer analyzing sediment samples from the Raritan and Hackensack Rivers, collected from boat docks, the experience nudged her in another direction. The rising junior, a biotech major, found that she may not have the patience to be an academic scientist. “I’d like to go to graduate school,” she said, “but I’m thinking of studying genetics and looking into careers in industry.”

Hu wasn’t alone in finding out that what sounded so simple – collect samples, store them, spike them, watch the results – wasn’t simple in practice. In Finland, students got their samples by using a grab sampler – a big metal jaw attached to block and tackle – off the stern of a research vessel. In New Jersey, they used a smaller, but similar device attached to the end of a long pole and manipulated by hand. In China, they used shovels.

The results didn’t always come quickly, and they weren’t always what the students expected. That, Young

reminded them when they came home, is part of the scientific process.

“Sometimes students think because they didn’t get the results they were expecting, that they didn’t get results,” Young said. “But they did get results. They reported interesting data. They all saw degradation differences (of the organic compounds) between the chlorinated and brominated compounds that reflected their hypotheses developed beforehand. It’s real data, and it gives us something to work with in the future.”

Logan Harper, an NSF-REU scholar from Lewis and Clark College assigned to the Finland project, described working in the lab every week day, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. “Our group spent a good part of our day pipetting (using a calibrated glass tube drawn to transfer and measure liquid) and analyzing results.

“Eventually, we were able to see microbes degrading the pollutants in the sediment – and that was exciting,” he said. “But we failed to get data for four out of six compounds.” Harper enjoyed working side by side with the four Finnish students in the program and though their culture was different he could see how “science is a universal language.”

Rutgers student Josh Roden spent the summer at South China University in Guangzhou. “The experience was as well rounded as it could have been, sometimes fun – I got to climb the Great Wall in Beijing – sometimes frustrating, sometimes rewarding,” said Roden, who will graduate in January 2014 with a double major in microbiology and biotechnology.

What he found most incredible was witnessing the scientific process from another perspective. “We worked with Chinese graduate students who were used to instruments that weren’t as sophisticated as those in the U.S., but it gave them an ingenuity and resourcefulness – a way of looking at things – we may not have thought of."

Roden returned to New Jersey for the lab sessions at Rutgers only to hop on a plane the following week to attend International Science Education, a research program funded by the USDA and Rutgers New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station that focuses on food crop diversification in the United States.

He spent 10 days studying the process of making fuel from sugar cane, flew back to spend a couple of a days at his parents’ home in Old Bridge and then headed for Montreal. “I love to travel. But this time," he says, “I just plan to relax.”