Jessica Valenti, founder of Feministing website, explores parenthood in newest book

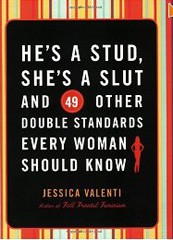

Feminist author Jessica Valenti does not have dull book titles: He’s a Stud, She’s a Slut...and 49 Other Double Standards Every Woman Should Know and Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World Without Rape are just two.

Her new book, due out this fall, is no exception: Why Have Kids?

Valenti, who made The Guardian’s 2011 list of Top 100 Most Inspiring Women, doesn’t have an answer.

“It’s not a yes or no question,’’ says Valenti, who received her master's degree in women and gender studies from Rutgers in 2002. “It’s a cultural critique of the way parenthood is idealized and not supported in any way and how that affects people and their happiness. You’re taught that you’re just going to have children and it will make you happy and fulfilled. After I got married, I decided to have a kid, but I always resented the idea that it was something I was supposed to do.’’’

Valenti, 33, is the mother of a 2-year-old, Layla, who was born two months prematurely after Valenti’s bout with preeclampsia.

After her own violent illness and the nearly two-month experience of trying to bond with her daughter in the NICU, Valenti suffered post-traumatic stress disorder, which can be common for women who go through a painful and difficult birth process, she says.

Her daughter is now healthy and Valenti has regained her equilibrium. But the birth and its aftermath left her with an understanding of just how grueling and unpredictable parenthood can be. “It’s definitely harder than you’re led to believe,’’ she says.”But I learned that you can’t have the expectation of perfect parenthood or a perfect child -- and that this is okay.’’

Valenti, who lives in Boston, is best known for founding the blog Feministing, which prompted a new wave of feminists to take their activism online.

“I was a 25-year-old who found it profoundly unfair that an elite few in the feminist movement had their voices listened to, and that the work of so many younger women went misrepresented or ignored altogether,’’ Valenti wrote in her goodbye column on the site last year.

Valenti, who started the blog in 2004, stepped down last year to make room for younger feminists, who she hopes will use the site “to build their career and platforms’’ -- as she has done. She also wanted to focus on writing and caring for her daughter.

Although Valenti leads a vital movement of young activists, she says many girls and young women are still disparaging of the word “feminist.’’

“A lot of people identify with feminist values but don’t like the label,’’ she says. “Conservatives have done a pretty good job of demonizing the term.’’

When she asks young women what they think when they hear the word “feminist,’’ the same stereotypes emerge: “They’ll mention bra burning, which didn’t even happen, by the way -- that’s a myth -- and man hating, very outdated but persistent images that are still being reinforced by the media.’’

When Valenti began writing about feminism, much of the cultural dialogue on women’s rights involved sexuality, she says. “There was a lot happening that was related to abstinence education. There were purity balls. So that’s really way I decided to focus on that in my books. ‘’

Her 2009 book, The Purity Myth, explores how the idealization of female virginity can be just as oppressive to women as images that focus on their sexual availability. “They’re two sides of the same coin,’’ she says. “Hypersexuality and the purity culture both say that women are only important because of what they do with their sexuality. Purity is really only applied to women. It’s very much tied up in ownership, women pledging purity to their fathers, who are trying to protect it.’’

In her book Yes Means Yes! Valenti argues that encouraging women to enjoy their sexuality without shame or condemnation could help reduce sex crimes.

Valenti’s high profile as a feminist spokeswoman -- she frequently appears on the news and talk shows --has resulted in a lot of hate mail.

“But that comes with the territory,’’ she says offhandedly.

Valenti honed her career as a writer and activist at Rutgers, where she also taught a class in gender and pop culture in 2009. “Rutgers was a huge part of how I got into the work I did,’’ says Valenti, who grew up in Queens, New York. “The Women and Gender Studies program was amazing and the teachers incredible.’’

Mary Hawkesworth, a professor of women and gender studies in the School of Arts and Sciences and a member of the graduate faculty in political science, says Valenti was an inspiring figure as both student and instructor. “She was keenly interested in engaging a new generation. When we invited her back to teach, the students were thrilled,’’ says Hawkesworth. “She has demonstrated why feminist commitments are essential for all those concerned with social justice. She has helped young women to realize that gender equality remains elusive in the contemporary United States.”

When Valenti speaks to students, including younger girls, she is careful not to lecture. She wants them to find their own answers.

“I’ll ask them, ‘Are guys called sluts, and why do you think that is? Why is there so much hatred for girls who are considered sluts? Why is there an assumption that if you want to be treated in a more respectful way, you shouldn’t be sexual?’ It’s best to ask a lot of questions,’’ she says. “They’ll get there themselves.’’