Sandra Day O’Connor’s Former Law Clerk Reflects on Her Legacy

Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court and who wielded great power as a moderate and pivotal swing vote, died today at the age of 93.

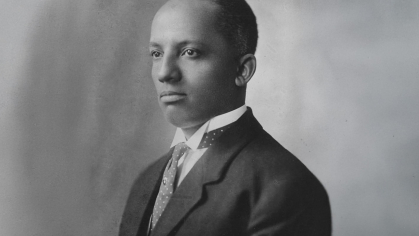

Gary Francione, a Rutgers Board of Governors Distinguished Professor of Law, clerked for O’Connor during the 1982 term, shortly after she was appointed to the Supreme Court.

Francione shares his reflections on his time working with the powerful justice.

What do you most remember and admire about her from your time working as her law clerk?

Justice O'Connor, or SO'C (pronounced "sock", which is what we actually use to call her) was conservative but she was not an ideologue. She always listened. She loved to discuss the fine points of precedent, but also really enjoyed talking about the jurisprudential and philosophical ideas that were involved in an opinion. Clerks in some of the other chambers had very little actual contact with their justices. We had a great deal of contact. Her door was always open to us, and she welcomed us in to talk to her whenever we wanted. Every afternoon, at 4 p.m., she got together with us, and we snacked on popcorn (we had a popper in our chambers) and discussed the day. We often had dinner at her house. (I was responsible for doing the popcorn popping, by the way, as the popper was in my office.)

Justice O'Connor visited Rutgers in the early 1990s. She gave a lecture at the Newark Law School. She spent a day with our faculty and students, and we had a lovely dinner where alums and others could meet her. It was a lovely visit.

What did her appointment do for women’s rights, women in the workplace and women in the legal field?

I think it had a great deal of impact as far as the law is concerned. The legal profession became less of a male-dominated enterprise as a result of her appointment. That said, the legal profession—and every institution—needs to go further to address the sexism and misogyny that is the legacy of patriarchy and is what Justice O’Connor faced when she started in the legal profession.

What was it like working for the first woman on the Supreme Court? Do you think it shaped her approach to her legal opinions?

It was wonderful. I had a great relationship with her. We all did. I had a sense that the clerks in our chambers had the best experience in terms of contact with our justice. She was very informal. I remember the first time she called me on the internal phone and asked me to come in to talk with her. She started, "Gary, it's Sandra..." I never called her "Sandra," but I am quite sure she would have been fine with it if I did.

If you are asking whether I think her being a woman shaped her approach to opinions, yes, of course it did. I do not think it would be possible not to have one's approach to opinions be affected by being a woman, just as it would not be possible to not have one's status as a person of color affect one's approach. I am certain that Justice Thurgood Marshall's being Black affected his approach as well. (Marshall was a wonderful person by the way.)

What do you consider her greatest legacy?

She was a great coalition builder. She had great skill in that regard. She produced a majority better than anyone else did when I was there. As far as substance is concerned, I believe that her building a coalition in the1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision that kept abortion as a fundamental right (until the recent crew came along) was monumental. In my view, women must have the right to choose if there is ever to be equality. By the way, the "undue burden" test that became the law of the land in Casey was first articulated in my year in her dissent in City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health, which also upheld reproductive rights.