Rutgers Botanist Contributes to MoMA Exhibit on Abstract Artist Hilma af Klint

Botanist Lena Struwe’s research revealed af Klint was not only an abstract painter, but also a skilled scientific illustrator

Rutgers botanist Lena Struwe grew up only 30 miles from where the renowned Swedish artist Hilma af Klint had lived and worked.

“When I was a child, our family used to sail in the summers around the islands where af Klint had lived,” said Struwe, director of the Chrysler Herbarium and a professor at the Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences. “But, despite that it was more than 100 years after her birth in 1862, she was then still unknown as a groundbreaking artist.”

Af Klint, who died in 1944 at age 81, is considered to be one of the earliest pioneers of abstract art, but her oversized abstract paintings were not seen for decades after her death, following her wishes.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York recently acquired a portfolio of drawings by af Klint, titled Nature Studies, and asked Struwe to participate in a research project in preparation for an exhibition.

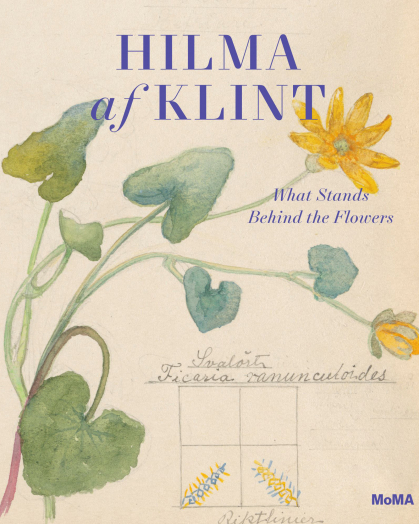

The portfolio of 46 drawings, featuring wildflowers, weeds and edible plants, is on display through Sept. 27 in Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers. Af Klint painted them during the spring and summer of 1919 and 1920 at her studio outside Stockholm, Sweden.

“When I saw these drawings for the first time, I was astonished,” said Struwe, who identified, updated and categorized the plants af Klint had painted. “These are traditional botanical drawings of common plants but with an unknown and unique dimension.”

After being asked by MoMA, Struwe researched af Klint’s early education, botanical literature and which teachers she had in natural sciences. She also contributed to the interpretation of the abstract diagrams that are associated with each species.

The museum reached out to Struwe at the recommendation of the New York Botanical Garden, where she worked before coming to Rutgers. Her research would soon reveal unexpected and previously unknown aspects of af Klint’s scientific knowledge and the ways her early botanical experiences might have shaped some of her art.

“I know by heart all these plant species that Hilma painted; they are part of our Swedish culture and folklore,” Struwe said. “I’m so familiar with the landscapes Hilma lived in and the lives and features of these plants, from the first signs-of-spring bright yellow coltsfoot flowers to the unassuming sedges in the meadows.”

Many of the plants af Klint painted are present in the northeastern United States as weeds, like dandelions, which happen to be one of Struwe’s current research subjects.

As part of this project, Struwe reached out to Johannes Lundberg, curator in the Botany Department of the Swedish Museum of Natural History, and asked him to look in that museum’s collection of fungi and plants for specimens collected by af Klint. Lundberg found seven scientific drawings of mushrooms made by af Klint in their archives. These were rediscovered after being forgotten for many decades.

It is now clear that af Klint was not only an abstract and traditional painter, but also a skilled scientific illustrator, hired to make botanical drawings of fungi for a book that never was published.

“People have mostly focused on Hilma af Klint’s fantastic abstract art, but from our research we now know that she was a holistic artist, and her paintings had deep meaning,” Struwe said. “We’ve discovered that, from an early age, she was educated in natural history, especially plants, and was taught by some of the foremost field botanists of the 1870s.”

Through these botanical watercolor paintings, af Klint sought to reveal, in her words, “what stands behind the flowers,” reflecting her belief that studying nature uncovers truths about humanity.

Each botanical illustration of a species is paired with a diagram, all different and depicting the properties she perceived they had. Some examples are concentric circles, a pinwheel of primary colors, checkerboards of dots and bright arrows, or crosses sunken in the ground.

“This exhibition and the research leading up to it have expanded our understanding of Hilma af Klint’s practice,” said Jodi Hauptman, the Richard Roth Senior Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints, MoMA, and the curator of the exhibition. “This is an artist with a deep interest in the natural world. We have learned that her plant knowledge and formal and informal botanical experience has shaped her artistic vision.”

Struwe details her discoveries in an essay titled, The Botanical World of Hilma af Klint in the printed, well-illustrated exhibition catalog edited by Hauptman, Hilma af Klint: What Stands Behind the Flowers that accompanies the exhibition; the publication includes additional essays and selections of af Klint’s writings.

Struwe explained, “There is still so much left to discover in her work, this is just a first scratch on the surface of her understanding and interpretation of the world around her, seen and unseen, scientific and spiritual.”

Struwe consults with MoMA for their Drop-In Drawing sessions featuring nature journaling that will be held as part of open house events for the public on Fridays in July and August this summer. Also, she and Hauptman are giving a talk later this month about Hilma af Klint and her botanical world at an international conference about historical female naturalists in Dijon, France.

Struwe is both thrilled and a bit bemused that she has now become the go-to expert on Hilma af Klint’s botanical world.

“I never expected my memories of wildflower meadows, well-used field guide floras, and long summer vacations would help me in future scientific and art history endeavors in the United States. I want to continue to create bridges of shared knowledge and excitement between art and science.”