Researcher Who Studies the Sense of Touch Named Rita Allen Foundation Scholar

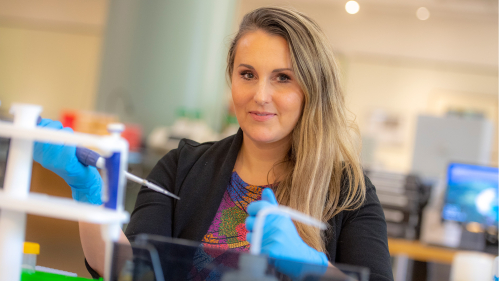

Victoria Abraira’s grandmother had trouble seeing or hearing when she was in her 90s during the final years of her life. But Abraira said the matriarch of her family always knew when she came to visit simply from her touch.

“She could feel that it was me when I touched her,” said Abraira, an assistant professor of cell biology and neuroscience in the School of Arts and Sciences. “She knew right away that I was there.”

Abraira’s research into the sense of touch and how it helps us to move, socialize and feel pain has earned her recognition as a 2023 Rita Allen Foundation Scholar. She is one of only nine scholars to earn this year’s award for early-career leaders in biomedical sciences whose research holds exceptional promise for revealing new pathways to advance human health. Abraira will join a distinguished group of honorees who have made fundamental contributions to their fields and historically have gone on to earn the most prestigious honors including the Nobel prize.

“The first sense we feel when we are born is touch and it is the last sense before we die,” said Abraira, whose laboratory operates within the W.M. Keck Center of Collaborative Neuroscience at Rutgers. “But it is the sense that we cannot understand as easily. While we can shut our eyes and understand what it might feel like if we were blind or plug our ears and understand what it may be like if we couldn’t hear, we can’t do this with touch. That’s why this research into touch is so important.”

Using methods in molecular genetics Abraira and her research team have genetically altered neurons in mice to see how it affects their spinal cords and behavior. Their goal is to gain a better understanding of what happens to the human spinal cord after injury, and whether the chronic pain state can change the nuclear structure of a cell.

She and her team are examining how touch could alleviate chronic pain, looking at the hormone oxytocin, often known as the love hormone, which regulates the body’s response to touch both in mice and humans. It also regulates the response to stress while controlling bodily functions. Gaining a better understanding of touch, she said, could help those suffering with anxiety and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and neurological disorders like autism and attention deficit disorder which often results in sensory overload and makes it hard for someone to cope with their surroundings.

While touch leads to the release of oxytocin in mice brains, the response in humans is not fully understood. Still, researchers believe that the release of oxytocin from the hypothalamus region of the brain and the production and release of cortisol from the amygdala during times of stress and fear is the reason we respond differently depending on who is doing the touching, a friend or loved-one or a stranger.

Neuroscientists like Abraira believe that a combination of a non-opioid analgesic like synthetic oxytocin, used to start or continue labor or to control bleeding after delivery, might be a successful therapy along with deep tissue massage for those living with chronic pain.

“For a really long time the studies in pain looked at touch as detrimental,” said Abraira. “But now we are exploring how touch, like vibration or deep tissue massage can alleviate pain and be used with a non-opioid, non-addictive therapeutic like oxytocin to provide relief for so many.”