Remembering the Women Who Made History 100 Years After New Jersey Ratified the 19th Amendment

Ann D. Gordon, a research professor emerita, shares insight into the lives of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony

This week marked 100 years since New Jersey became the 29th state to ratify the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote. Within six months, 19 states followed and the constitutional amendment became law.

The action capped off a decades-long fight by a determined group of women including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who tirelessly traveled the country to convince the American populace that women were no less deserving of the vote than men.

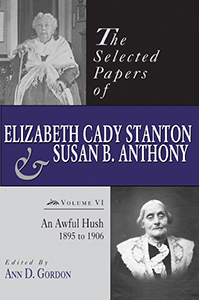

Their lives and work are documented in the six volumes that make up The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, edited by Ann D. Gordon, a research professor emerita in the Department of History at the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

The collection, published by Rutgers University Press, represents the culmination of an extraordinary effort to gather and catalog all the writings of Stanton and Anthony. The project took nine years to complete. By the end, the researchers had amassed some 14,000 documents collected from more than 200 libraries.

In 1992, with the help of Rutgers historians, graduate assistants and undergraduates, Gordon began the challenging process of transforming the Stanton and Anthony letters into a book. The initial volume appeared five years later; the last would be published in 2012. “I came to this not knowing a great deal about the history of women’s suffrage,” she notes. Working on the project and the book made her an authority.

To get a sense of Stanton's and Anthony’s historical importance, Rutgers Today sat down with Gordon, who shared her insights into two very different women who were fiercely united by a single goal.

Rutgers Today: Given that both women died more than a decade before the ratification of the 19th Amendment, how important were they, from a historical standpoint, to the struggle?

Ann Gordon: I think they’re very important if we think about this as a social movement that took many years to get attention; it also took time for women to gain the courage to speak out about it. After the Civil War, Anthony and Stanton were willing to travel, city to city, around the United States talking about women’s rights and suffrage, and they were largely responsible for making this a national conversation.

RT: The 1848 women’s convention in Seneca Falls, New York, is widely regarded as having launched the movement for women’s suffrage. What role did either of the women have in the convention?

AG: Stanton was one of the women who convened it, and it was Stanton who got the organizers to sit down before the convention and draw up a Declaration of Sentiments that proclaimed “all men and women are created equal”; she also rewrote the Declaration of Sentiments' list of grievances. It’s said that Stanton pushed hard for women’s disenfranchisement to be among those grievances.

RT: When did the struggle for women’s suffrage become a true national movement?

AG: Before the Civil War, nobody doubted that the states had the right to set voting qualifications, and so those in the movement were working toward change in the states. After the war, the focus changed. The passage of the 15th Amendment granting all men the right to vote offered a new possibility: Congress could grant women those same rights. So, the struggle became a national movement, in that sense. This was also the time when Anthony and Stanton became hugely popular as speakers – they packed the houses.

RT: Would you characterize Anthony’s attempt to vote in the 1872 federal election – an attempt that led to her arrest – a radical act? Women were not allowed to vote at the time.

AG: It came as part of the movement in many parts of the country. The idea was you’d try to register to vote, be blocked from registering and then you’d sue, based on the idea that the 14th and 15th Amendments didn’t just give black men the right to vote; it gave all citizens those rights. Women in California; Washington, D.C.; Connecticut; Michigan; and elsewhere had done this before Anthony, and that’s what Anthony thought she was going to do. But she and 15 other women who tried to vote in that election were actually allowed to register and vote; that was a decision made by the men supervising the election. Anthony and the women, however, were subsequently arrested. She was the only one to stand trial. One of the historical mysteries is why the authorities came down on Anthony’s action as heavily as they did. Clearly, they thought it would have a deterrent effect, given her celebrity.

RT: Did you emerge with a favorite between the two women?

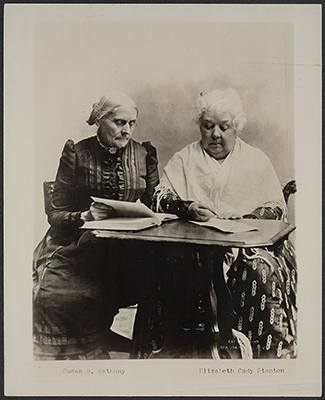

AG: Anthony, for sure. I like her practicality: I’d travel with her over anybody. I also think she was much more flexible about getting along with different kinds of people. She might be staying at the home of a racist who supported women’s suffrage, but then she’d go into town and speak at a black women’s club. In her photos, she looks a little scary, but I think that’s because she was self-conscious about her wandering eye.

RT: In editing the papers, did anything surprise you?

AG: I was unprepared for Stanton’s and Anthony’s roles in building a national movement. If you look at where and when petitions demanding women’s suffrage were filed, they actually follow Anthony’s and Stanton’s speaking engagements up and down the country. I was also surprised by the viciousness of the male opposition. I suppose I shouldn’t have been: it’s been 100 years, and look at how low women’s numbers in the legislature are even today.