Paul Robeson's 1919 Rutgers Commencement

A year after his father died, Paul Robeson stood before the mostly white audience gathered for Rutgers’ 1919 Commencement and delivered an address that he had entitled “The New Idealism.” From a young age, the 21-year-old had been trained by his father, William, a former slave turned pastor, in both the classics and oratory. So vocal delivery was perhaps as important as the message. But he did have something important to say.

Unity, Robeson told the crowd at the Second Reformed Church in New Brunswick, “is impossible without freedom, and freedom presupposes a reverence for the individual and a recognition of the claims of human personality to full development. It is therefore the task of this new spirit to make national unity a reality, at whatever sacrifice, and to provide full opportunities for the development of everyone.”

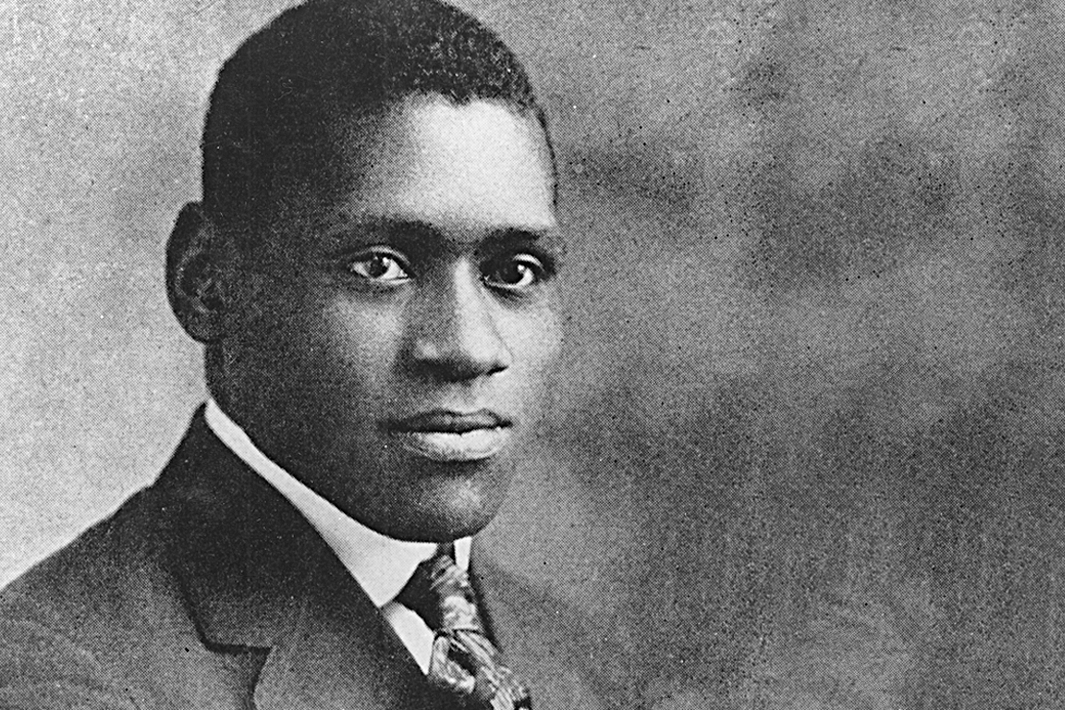

Paul Robeson as pictured in his yearbook in 1919

Over four years, Robeson had amply demonstrated his “development” – as a star athlete, a Phi Beta Kappa member and an oratorical champion, among other achievements. His late father, who’d pressed all five of his children to exceed expectations, would have been proud. But in 1919, “national unity” was a pipe dream. Segregation was the law of the land, lynching was rampant in the South and the Ku Klux Klan, glorified in D.W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, was newly reborn and empowered.

As Wayne Glasker, an associate professor of African-American and 20th-century U.S. history at Rutgers University-Camden, points out, “With World War I now over, we had made the world ‘safe for democracy,’ but there was no racial equality at home.”

Robeson knew that. “The New Idealism,” though nuanced in its wording, challenged those of “the favored race” in the audience to “catch a new vision and exemplify in your actions this new American spirit. That spirit which prompts you to compassion.” It’s perhaps no coincidence that he said this just two weeks after handing in his senior thesis.

“It was titled ‘The Fourteenth Amendment: The Sleeping Giant of the American Constitution,’ and it deals, in part, with the issue of black citizenship rights,” says Edward Ramsamy, chair of the Department of Africana Studies at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. “I think he was acutely aware of those racial dynamics. But he also wanted to make his contribution to transcend that.”

At commencement, for instance, Robeson spoke of “reconstructing our entire national life and molding it in accordance with the purpose and the ideals of a new age. …We can expect a greater openness of mind, a greater willingness to try new lines of advancement, a greater desire to do the right things and to serve social ends.”

His senior thesis, though written in legalese – he planned to go to law school – piggybacks on the idea. Ratified by Congress in 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment recognizes “equality before the law,” as Robeson put it. It applies to “persons of every race, rank, and grade,” he wrote, and provides “relief against arbitrary legislation by the State.” It would take, however, another 35 years, with the ruling of the Supreme Court case, Brown vs. Board of Education, to apply it to segregation.

“Paul Robeson put together the intellectual foundations for the development of law and understanding the ramifications of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Ramsamy notes.

In 1919, however, he wasn’t looking to upset the status quo. Like many, he shared in the philosophy of the era’s most influential African American, Booker T. Washington, a former slave turned writer, orator and first president of the Tuskegee Institute. The keys to black progress, Washington believed, were education and entrepreneurship, not desegregation. For Robeson, “in those early years,” Ramsamy says, “it was sort of idealism coupled with Washington’s type of approach to self-empowerment.”

But another approach was taking shape, one advocated by the recently established NAACP and one of its founding members, W.E.B. DuBois. Only changes in the law, they believed, would enable African Americans to realize their potential. In due course, Robeson would come to agree. Meanwhile, he was leaving Rutgers a changed man. “Rutgers allowed his multifaceted skills to develop – his athletic skills, his oratory skills and his intellectual interests,” Ramsamy says.

“Rutgers did help shape him,” Glasker concurs. “It gave him confidence in his abilities, and he had demonstrated his talents and his merit. And I think it probably raised his expectations.

“The problem, though, is that if you have heightened expectations and then life doesn’t quite fulfill them, it can leave you not only determined, but also frustrated. And part of the frustration is the slow pace of change.”

Rutgers is honoring Paul Robeson’s legacy as a scholar, athlete, actor, singer and global activist in a yearlong celebration to mark the 100th anniversary of his graduation. Check back with Rutgers Today throughout the year as we present a special series chronicling Robeson’s life and his influence on generations. Read previous articles in the series for an overview of his life, an exploration of his father's influence and his childhood in Somerville, his time on the football field at Rutgers, all around excellence as an undergraduate student and his rivalry with Princeton.

Learn more about the celebration by visiting robeson100.rutgers.edu or by following #Robeson100 on social media.