Pandemic Shapes Rutgers' Move to Online Learning for State’s Contact Tracers and More

This summer, as the state looked to ease restrictions put in place in response to the coronavirus, Rutgers took on the crucial role of preparing a corps of contact tracers to identify people who were exposed and break the chain of transmission.

But there was an added challenge: how do you train people in this vital role when you can’t bring them into a classroom and provide instruction in traditional ways?

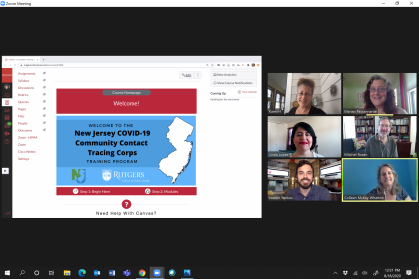

Marian Passannante, an associate dean and professor at the School of Public Health, and Colleen McKay Wharton and Mitchel A. Rosen, from the Center for Public Health Workforce Development, teamed up with Karen Harris, an instructional designer at Rutgers Teaching and Learning with Technology (TLT), to develop the course online. They built on what the university had learned since the spring when most classes made the pivot to remote instruction.

The contact tracers learned to be disease detectives who work backwards from one confirmed infection to identify others who might now be at risk and would spread the disease if they were not notified to quarantine. The role is not only essential, it’s complicated requiring both an ability to interview people about sensitive subjects and an awareness of privacy laws. The team of educators created 18 hours of modular instruction. A perfect score on one module is required to proceed to the next.

“It was two to three weeks of working literally 10 in the morning to 10 at night,’’ said Harris from TLT. “I think people underestimate how much time and effort it takes to build an online course. It’s hard work to make learning online easy.”

After many late nights, the team was able to roll out the new course in June. Graduates of the training went to work as contact tracers in positions at local health departments around the state. New students continue to sign up. More than 1,500 new and local health department contact tracers have been trained through the program so far.

“The people taking it are, for the most part, grad students at Rutgers and other schools around the state,” says Passannante. “Most of them have some public health, psychology or sociology background, so they’re already good at interviewing people about difficult subjects. They seem to really enjoy the course.”

Making courses like this possible is essential to the mission of TLT, which provides instructional technology and course design support throughout the university as part of the Division of Continuing Studies.

“Back in the spring, when the university pivoted to online learning, we were responding to an emergency situation,” says William Pagán, TLT’s director of Instructional Design. “Now we’re pivoting from reactive to proactive. It’s not enough to just put a lot of content up; you have to be very purposeful in how you do it. What does the student need to learn? How do you to get them to that point? You almost need to reverse-engineer things.”

Continuing Work for the Fall

Instructional designers offer a lifeline for faculty trying to adapt traditional courses to the remote-learning world that continues this semester at Rutgers.

Staff within TLT helped transform a public speaking course at Rutgers School of Communication and Information (SC&I), which is part of the core curriculum. Some of the assignments, which require delivering talks to an audience, can be anxiety-provoking enough in the classroom. But how do you fulfill that requirement when you’re off campus?

Nikolaos Linardopoulos, an associate teaching professor at SC&I and coordinator of the “Public Speaking” course, said that TLT’s Online Teaching Workshop Series was essential in helping their instructors prepare for the online transition for the fall semester, showing them among other things how to effectively substitute streamed or pre-recorded presentations for in-person ones.

“We’ve been able to give the students options,” Linardopoulos says. “We know now that everyone doesn’t have equal access to Wi-Fi or even a quiet place; of course, some resources, like the lab on campus, or the library, remain unavailable. But, if you don’t have the software to do streaming video, we can provide it as a download. If you’re not able to do the class synchronously, you can do it asynchronously. We are being as accommodating as possible.”

Instructional designers have been busy working around the university. They provided one-on-one assistance to faculty at the School of Business-Camden, which features several fully online degree programs. They’ve developed the Rutgers School of Environmental and Biological Sciences Online Teaching Toolkit, resources tailored to a variety of different disciplines – from engineering to biology – that provides links to resources, grant-funded videos, and peer-to-peer mentoring opportunities.

At Rutgers University-Newark, TLT has provided support for the P3 Collaboratory. More formally known as the Collaboratory for Pedagogy, Professional Development and Publicly Engaged Scholarship, the unit was designed as a kind of experimental space, a hub on campus to distribute training and research, a place where people can talk about a variety of issues and ideas, says assistant professor of practice Catherine Clepper.

“We’ve all been learning in the moment,” Clepper says. “But we’ve seen an incredible amount of progress just in the last few months. And I think when we do, eventually, emerge from this situation, we’ll all be much nimbler educators, with important skills in our tool belts.”