Aram Sinnreich’s new book ‘The Piracy Crusade’ argues for fair model, such as Spotify, which rewards artists and business

Aram Sinnreich is working to debunk the myth that music lovers who share files online are pirates committing a form of theft.

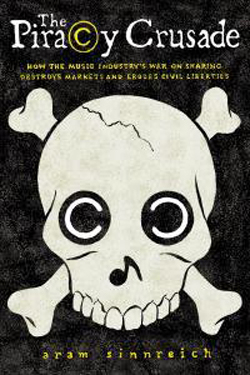

Ever since the debut of Napster more than a decade ago, Sinnreich – an assistant professor of journalism and media studies in the School of Communication and Information – has seen music sharing as beneficial to the industry. Prosecuting individuals who share files is an attack on free speech, he argues in his latest book, The Piracy Crusade: How the Music Industry’s War on Sharing Destroys Markets and Erodes Civil Liberties (University of Massachusetts Press 2013).

He believes American corporations that control much of the world’s existing music content have hijacked intellectual property and copyright law to serve their own short-term interest. These corporate tactics are detrimental to cultural and technical innovation and their own long-term interest, Sinnreich says.

The emergence of “cloud” music services like iTunes Match and Spotify has given Sinnreich some hope that the recording industry will change its tune. “2011 was the year of the big cloud music companies,” he says. “Streaming went up 30 percent last year, and Spotify is a major source of revenue for the major (recording) labels. There are signs they’re beginning to be a little more intelligent.”

But the darker view of the industry’s mindset still prevails. His view evolved soon after the debut of Napster, a site the industry successfully fought to shut down. At the time, Sinnreich was working for a consulting company and had recording industry companies as clients. He commissioned surveys of music fans concerning their use of Napster. “I asked about their listening habits and found – counterintuitively – that people who used Napster were likely to spend more money on music, and that Napster was a great influencer,” Sinnreich remembers. “I ran breathlessly to my clients and said, ‘Isn’t this great?’”

Sinnreich discovered, however, that his clients weren’t interested in influencing their customers through Napster. Their business model saw music as a resource that they needed to control. Instead of seeking partnerships with entrepreneurs like the founders of the music sharing site, they set out to destroy them. And instead of making access to music as easy as possible for their customers, they went so far as to sue and prosecute them by the tens of thousands. Driven by their lawyers and lobbyists, Sinnreich believes recording companies “are structurally incapable of thinking of their own, long-term strategic benefit and are completely focused on short-term gains.”

Sinnreich says the federal government, through the office of the United States Trade Representative, has pressured other countries to adopt American-style copyright and intellectual property laws, such that the reach of the government and large recording companies, is effectively extended into other countries and cultures.

“Intellectual property laws are used as a kind of economic weapon in global economic warfare,” Sinnreich says. “The U.S. uses the threat of trade sanctions against its treaty allies to force them to adopt laws whose effect is to siphon off dollars from those countries and their industries into the U.S. recording industry’s pockets,” he says. “This opens up the policing of information in those countries and essentially allows us to spy on them.”

Sinnreich acknowledges that there are real pirates out there, sometimes supported by their governments. They don’t share content; they steal it and sell it without paying the people who produced it. The Chinese government, he says, turns a blind eye to its companies’ unauthorized use of American intellectual property as a way to undermine American economic power. Russia is full of freebooting businessmen and shakedown artists.

“India and Brazil take a different tack,” Sinnreich says. “They’re developing economies, trying to get their cultural industries off the ground. They’ve made a decision in some cases not to adhere to our dictates on intellectual property.”

Sinnreich does not defend the pirating of music. He wants recording artists to get paid, and he doesn’t want recording companies to fail. In fact, he sees some signs that the big recording companies are easing off their militant, anti-sharing stance.

For more information, please contact Ken Branson of Rutgers Media Relations at (848) 932-0580 or kbranson@ucm.rutgers.edu