Mingus at Mason Gross

The Mingus Project celebrates jazz legend Charles Mingus, unites students with master musicians

‘There was a perception that his music was very difficult and for the chosen few. It shows you how much things change with time. We have these youngsters just playing the life out of it.’– Sue Mingus

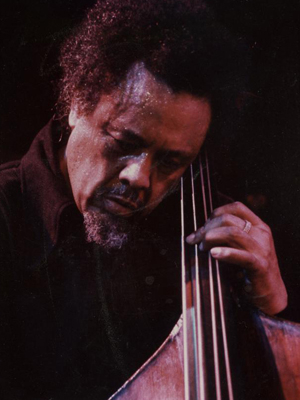

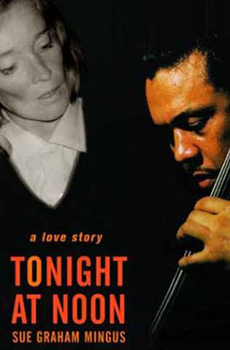

Jazz legend Charles Mingus died of complications from ALS in 1979, at age 56.

But thanks to the tenacity of his widow, Sue Mingus, it seems as if the endlessly innovative bassist, composer, band leader, and political activist never left the stage.

Sue Mingus is determined to share her late husband’s music with young people. She closely curates his social-media presence, oversees a Mingus high school festival and competition, and finances The Mingus Project, a program in which musicians and scholars conduct intensive master classes with Mason Gross School jazz students. Rutgers launched the program in 2013 and recently formed the Rutgers University Mingus Ensemble. The group is set to perform Wednesday, March 11, at the Nicholas Music Center.

“Mingus left so much music,” Sue Mingus says. “It’s so varied and rich; it covers the waterfront. Kids seem to really enjoy playing it.

“There was a perception that his music was very difficult and for the chosen few. It shows you how [much] things change with time,” she adds. “We have these youngsters just playing the life out of it.”

Mason Gross jazz students say The Mingus Project grants them access to “the real world.”

“Before there were institutions for [learning] jazz, this is how you learned,” says Dan Giannone, a drummer who has participated in numerous classes with musicians from the Grammy-winning Mingus Big Band, the Mingus Orchestra, and the Mingus Dynasty. All three tribute bands, which Mingus began to assemble right after her husband’s death, have included Mason Gross alumni and faculty members, such as jazz studies chair and trombonist Conrad Herwig, bassist Kenny Davis, pianist Orrin Evans, and trombonist “Ku-umba” Frank Lacy.

The bottom line, Giannone says: “Playing with people greater than you makes you better yourself.” The Mingus Project allows him to do just that, on a regular basis.

‘The real world’ at Mason Gross

Herwig, who launched the The Mingus Project with Sue Mingus’ support, says the initiative focuses on Mingus as composer and improviser. Guest artists visit five times a semester, perform a composition, discuss related concepts, engage in a Q&A session, and listen to student performances. Guest artists offer critiques and sometimes perform with students. Participants visit New York City to catch guest artists at the tribute bands’ shared Monday-night Jazz Standard residency.

“Seeing the Mingus Big Band, I had tears of joy on my face,” Giannone says. “They exemplify what I want to do with my career. They’re living it up on the bandstand. To see that joy makes you feel it’s still possible to play with joy.

“We sit in school and study and study,” Giannone adds. “It’s [inspiring] seeing how much fun they’re having. They make it [seem] effortless.” Besides, he adds: “This is how you learn the most. The Mingus program takes us out of the [staid] ‘Study of Music.’ ”

That’s exactly the point, says Abraham Burton, a master’s student and a tenor and alto sax player in the Mingus tribute bands. Burton, set to direct the Rutgers University Mingus Ensemble, says the Mingus-Mason Gross connection allows Herwig to maintain “that bridge between academic concerns and real life [as a musician] out there, doing it.”

Burton says Mingus’ compositions are ideal teaching tools because they embrace a broad swath of musical styles, including swing, classical, bebop, and the blues.

“Mingus opens you up as a young musician to what can be,” Burton says. “He loves to explore. His music keeps you on your toes.”

Student bass player Ross Garlow says delving into Mingus’ compositions with the musicians who have been steeped in them for decades has emboldened him.

“Guys like [Fred] Hersch, [Frank] Lacy – they’ll come in and rip us apart but do it with motivation and inspiration,” Garlow says. “That only usually happens in the real world.

“They understand our faults and explain what we can do about them,” Garlow adds. “Students who don’t get up and play in front of people play in front of these guys.

“You want to be ready to play in front of Orrin Evans,” Garlow says. “Why else am I here? If they didn’t bring in these guest artists, you might not get past it.”

‘The Nostradamus of Jazz’

Scholar and trumpeter Ken Pullig, retired chair of jazz composition at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, delivers lectures and plays Mingus recordings for Mason Gross jazz students. He’s been teaching Mingus’ music for nearly 40 years.

“His music is very inspirational to young musicians,” Pullig says. “There’s something daring and unique about [his compositions], and that seems to resonate with them finding a life in music. What they learn is the honesty of his music and trying to be true to who you are. This is a good message for students to hear. Mingus used to say, ‘I’m just trying to play the truth of who I am.’ ”

Herwig says The Mingus Project isn’t merely about schooling students in jazz history. He says he believes Mingus, long regarded as a fiercely passionate figure committed to troubling the waters in music and in life, has plenty to offer the 21st-century musician.

“Everything he was involved in – civil rights, equity for all people – his broad political perspective is as fresh today as when he wrote the songs,” says Herwig, who has dubbed Mingus 'The Nostradamus of Jazz.' “…Mingus was ahead of his time.”

And according to Lacy, it’s about time Mingus received his due in the classroom.

“These guys didn’t go to school for music,” says Lacy, a Mason Gross alum and a trombonist with the Mingus Big Band since 1989. “Their music wasn’t in universities. It’s great that it could be talked about in a university setting.” He likens sharing Mingus’ work with young jazz musicians to serving as “a link in the chain.”

But student Garlow says he’s just as grateful for how The Mingus Project nudges him to step outside the practice room and onto the stage.

“You can’t appreciate Mingus’ music in an institutional way,” Garlow says. “We must catch an audience with our music. The way you learn is going out and playing, falling on your face. That’s the way you really learn.”