Historic Case Striking Down Party Line on New Jersey Ballots Shaped by Rutgers Expertise

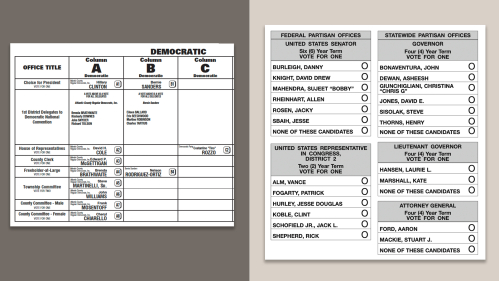

New Jersey’s voter ballots may look very different in the June primary as a result of a lawsuit brought by Rep. Andy Kim’s campaign for U.S. Senate. A federal court judge recently issued a preliminary injunction striking down the use of the party line that groups all candidates running together on the ballot rather than grouping them by office they seek as is done in the rest of the nation. The New Jersey ballot has drawn criticism from a growing grassroots movement because it isolates candidates not endorsed by political parties in a less prominent position – affecting their election chances.

A group of Rutgers experts, including alumni, were heavily involved in shaping the case that could transform politics in New Jersey. Julia Sass Rubin, a professor at the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, has conducted extensive research on the influence of the party line and served as an expert witness in the case. Attorneys on both sides attended Rutgers Law School including two members of Kim’s legal team, Yael Bromberg (who now teaches "Election Law and the Political Process" at Rutgers Law School) and Brett Pugach (both LAW’11). The third member of Kim’s team, Flavio L. Komuves, is a Rutgers College graduate who previously served as Deputy Public Advocate for New Jersey. Even U.S. District Judge Zahid Quraishi, who wrote the decision, is a Rutgers Law School graduate.

We talked to some of the experts from Rutgers involved in the case about the significance of the decision and why this happened now.

When did the practice of putting party-backed candidates on the ballot line begin, and how did New Jersey become the only state to use it?

Pugach: Before there were primary elections, most parties just nominated candidates at conventions, based on a selection of a handful of party insiders pursuing their own private interests. In the early 1900s, New Jersey was at the forefront of a national movement for a direct primary election in which voters get to decide who their party’s nominee will be for the general election. In 1930, New Jersey passed a primary endorsement ban to prevent the parties from exercising undue influence. Over the decades that followed, county parties tried to find ways around this, including creating social clubs that essentially consisted of the influential members of the party, which would make their own endorsements but were not the official party entities, and thus could try to circumvent the primary endorsement ban.

In the 1940s, legislation was passed that allowed for bracketing in counties that used voting machines, which set the stage for the social clubs to use a county line to give an advantage to their endorsed candidates. Following a court decisions which struck down the primary endorsement ban as unconstitutional and a series of questionable state court decisions allowing for preferential treatment of certain candidates over others on the ballot, the official county party committees stepped into the place of the social clubs to give official party endorsements, preferred ballot position, and other advantages on the ballot to their endorsed candidates, largely excluding voters from the endorsement process.

What is the argument for abolishing the party line now?

Pugach: The lawsuit challenges the manner in which primary election ballots in 19 of New Jersey’s 21 counties are designed. This unique ballot design system gives an enormous electoral advantage to party-endorsed candidates featured on the county line, and punishes candidates who choose to exercise their constitutional right to not associate with candidates for other offices by casting them off to obscure portions of the ballot (colloquially referred to as “Ballot Siberia”) where they are harder to find, harder to know what they are running for or who they are running against, and otherwise appear less legitimate.

New Jersey’s primary election ballots are designed so as to provide a government-sponsored substantial advantage to the party-endorsed candidates over their opponents, based on the design of the ballot itself. This violates the First and Fourteenth Amendment rights of candidates (including the right to vote, equal protection, and freedom of association), fosters voter confusion and violates the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Have other candidates challenged “the line” previously?

Rubin: Yes, other candidates have challenged the county line. The original lawsuit, which is also being litigated by Yael, Brett and Flavio, was filed by six other candidates who were impacted by the county line in the 2020, along with New Jersey Working Families. That lawsuit is still in the discovery stage. Andy Kim’s lawsuit (along with co-plaintiffs Sarah Schoengood and Carolyn Rush) received expedited review because it was filed prior to the June 2024 primary.

Both lawsuits built on a grassroots campaign against the county line that began in early 2017 with the formation of the Good Government Coalition of NJ (GGCNJ), a nonpartisan organization with a mission of strengthening New Jersey’s democracy. A primary focus of GGCNJ was educating the public about the impact of the county line on New Jersey elections, politics and policy. Many other pro-democracy and grassroots organizations then helped to amplify that message.

Why was Andy Kim’s challenge to the party line successful now?

Rubin: The indictment of Senator Menendez, the national importance of the U.S. Senate race, and Andy Kim’s very effective messaging that built on the work of the grassroots, helped to shine a national spotlight on how the county line works and how it impacts our state, laying the groundwork for this decision.

Bromberg: Kim is a natural messenger for the longstanding call to abolish the line. He entered the race for Senate immediately upon the indictment of Senator Menendez for corruption, and had to contend with unprecedented, complicated dynamics resulting from First Lady Tammy Murphy’s rapid-fire endorsement by county party chairs [before she dropped out of the race].

Kim joins this call to abolish the county lines alongside scholars and advocates who have been leading the charge. He sought the litigators out who were involved in the separate related litigation. The case has attracted so much recent attention in part due to base building over the last four years since the original suit was filed, coupled by increased media and public awareness around this issue. In many respects, the efforts to abolish the line trace back to the democracy awakening accompanying the 2016, 2018 and 2020 elections. Voters don’t want the system to be rigged, be it in Georgia or in New Jersey, and want to ensure that their votes and voices count.

Does this change the way candidates will campaign in NJ?

Rubin: One of the impacts of the county line has been discouraging those who do not receive the party’s endorsement from running. Candidates understand that running off the line is ineffective so they tend to drop out if they are not selected for the line. This system has resulted in New Jersey having a large number of uncontested primaries, particularly for the state legislature and county positions. The county line also has contributed to our elected officials being overwhelmingly white and male, even as New Jersey is one of the most diverse states in the country. The political bosses who determine who gets the county line are overwhelmingly white and male and they tend to draw candidates from their own political networks, perpetuating the homogeneity.

The end of the county line will force both candidates and political parties to invest resources in communicating their ideas to the voters. Up until now, voters have not mattered very much because so few of New Jersey’s general election contests are competitive. That means that winning the primary translates into winning the general election for much of the state. The power of the county line primary ballot has enabled a handful of party insiders to determine who wins the primaries. As more candidates decide to run in the primaries and ballot design does not determine who wins, candidates will need to invest energy in earning voters’ support by informing them of where they stand on the issues.

How does this change the influence of party leaders and politics in New Jersey?

Rubin: The end of the county line will be an earthquake for New Jersey politics and policy. For most of the last 100+ years, our politics and policy have largely been controlled by political machines and the county line primary ballot has been their most powerful tool for staying in power. Although the machines will still have access to financial resources and some aspects of the patronage system, the end of the county line will greatly diminish their ability to control who is elected. That should enable new voices to enter the political space and bolster the willingness of elected officials to do what their voters want rather than what the political machines demand.

Your research showed the line gave party-backed candidates a 38 percent advantage in elections. How did you come up with that figure and does this change that?

Rubin: That figure is from an analysis examining how candidates for the U.S. House and Senate performed over the last 20 years when they were on the county line versus when an opponent was on the county line. There were 45 candidates in such split-endorsement contests. I found that each of those 45 candidates performed substantially better when they were on the county line than when their opponent was on the county line, with 38 percentage points the average difference in their performance

This is a preliminary injunction. What is next in the process?

Bromberg: The preliminary injunction will hopefully be protected on appeal and will secure fair 2024 primary ballots. Emergency motions to stay the preliminary injunction pending appeal were denied by the federal judge and the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. Notably, the New Jersey Attorney General separately concluded that he would not defend the law because it is unconstitutional. All of the county clerks have now withdrawn from the appeal. Only the Intervenor-Defendant, the Camden County Democratic Committee, is pursuing it now. We know that the public and the voters are in support of this common-sense, constitutional change. And, there have already been open calls by gubernatorial candidates for fair ballots in connection with the 2025 primary. It is just a matter of time for this judicial relief to become permanent, and for county line ballots to be relegated into the annals of New Jersey history where they belong.