Criminal Justice professor by day and children’s book author by night, Joel Caplan takes young readers on a Fantastic Awesome Funny Fun Day at School – and prompts them to open up to their parents

'Facilitating meaningful dialog can be a daunting task, and I think a lot of parents wish they could have these kinds of discussions with their children.'–Joel Caplan

Once upon a time, when Joel Caplan, an assistant professor at Rutgers School of Criminal Justice, picked up daughters Oriellah, 4, and Shailee, 2, from school, he asked, “What did you do today?” Their one-word answer was typical of many children: “Nothing.”

Then, he got creative. “You must have done something,” he said. “Did you go scuba diving? Did you ride a rocket ship into space?” At first, Oriellah kept answering “no,” and then she caught on, telling Caplan a story that was half-truth, half-fantasy: “We made cupcakes with play dough and shaving cream. They were just for pretend. But Ms. Lisa ate one and turned into a magic skating dragon.”

This imaginative dialogue was an ah ha moment, and Caplan knew he was on to something he wanted to share. The published children’s book author – his safety awareness-themed Strangers Can Hurt came out in 2011 – started scribbling thoughts on Post-It notes one night when he couldn’t sleep. By the time his family woke up, he had written the first draft of My Fantastic Awesome Funny Fun Day at School.

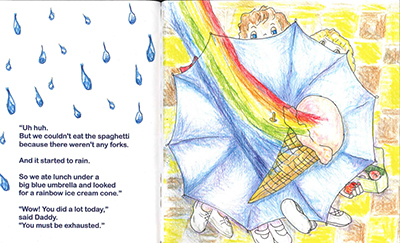

The 34-page book, published in May, follows a father who asks his daughter, Oriellah, what fantastically funny things happened to her during the day and describes her responses, such as “This morning we went bird watching with toilet paper tube binoculars. We swung in the trees with monkeys while waiting for flocks of migrating geese.” The illustrator, Leslie Goldstein Hager who is Caplan’s cousin, rendered Oriellah’s imagery in colored pencil.

“Facilitating meaningful dialog can be a daunting task, and I think a lot of parents wish they could have these kinds of discussions with their children,” says Caplan, who has noticed that conversing with his daughters has become easier with this imaginative back-and-forth. He has heard that the book has opened up dialogue with children of his friends and of people who attend his book signings. “I wanted to encourage parents and grandparents to be creative with how they ask their children about what they did during the day and not give up when they say ‘nothing.’”

Caplan also wanted the imagery to spark curiosity. “When I wrote, ‘Did you wave to the presidents at Mt. Rushmore or throw pennies into a Roman fountain?’, I meant the ideas to be catalysts for discussion, prompting the children to ask, ‘What is that? Where is that? Can we go see it?” he says. “The book is kid-tested. I read it to my daughters as I revised the draft to get their reactions to the verses. They helped me write it.”

He adds that the father-daughter dynamic in the book resonates with stay-at-home or work-at-home dads who increasingly are picking up their kids from school. “Regular conversation and bonding establish trust – whether it’s with mothers, fathers, grandparents or other trusted adults,” he says. “What matters is that the children know they have someone they can talk to.”

Though writing children’s books may seem like a leap from Caplan’s day job as a criminal justice professor specializing in risk assessment and victimization, there is a connection: Caplan uses proceeds from the sale of this book and Strangers Can Hurt to purchase hard copies of Strangers Can Hurt that he donates to police and fire departments, schools and public libraries nationwide. To date, he has donated 200 copies.

Caplan plans to continue his public safety series with a book that will teach young children about what constitutes an emergency and when to dial 911.