For Dreamers of the Future, Optimism Rules — Especially Among Americans, Researchers Find

Sociologists analyze what it means to dream and imagine future possibilities, and how people’s dreams differ

“Social location” – where class, race, gender, stage of life, or unexpected disruptions to one’s life place a person in the broader society – influences what, when, how and if a person dreams about the future.

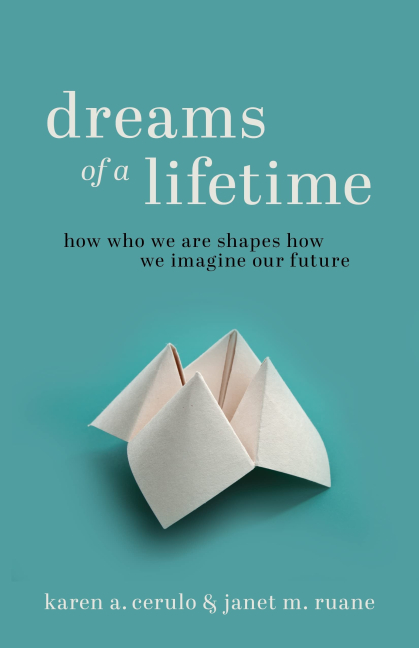

In other words, people are free to dream about possibilities like becoming a movie star, traveling worldwide, or getting a new promotion, but not all dreamers are equal, according to, “Dreams of a Lifetime: How Who We Are Shapes How We Imagine Our Future,” published this month.

Karen Cerulo, a Rutgers professor of sociology co-authored the book with Janet Ruane, Professor Emerita of Sociology at Montclair State University. The two spoke with nearly 300 people about their dreams for the future. They surveyed people of different social class backgrounds; different races and genders; and at different stages of life – newlyweds, new parents, people starting new jobs, recent immigrants as well as people facing serious hardships such as poverty, homelessness, serious medical diagnoses or unemployment.

“Jiminy Cricket’s promise, ’When you wish upon a star, makes no difference who you are. Anything your heart desires will come to you,” may be true for some,’ said Cerulo. “But for others, it is a false promise. We understand that class, race, gender, age and tragedy can create inequities in life’s opportunities, but we are also told anything is possible. Here, we show that dreams are restricted in ways of which we are not fully aware.”

Differences in Men and Women

According to the research, men and women are equally likely to dream of career accomplishments and having the opportunity to help others or donate large sums of money down the road.

Gender differences became more apparent with dream themes distributed along traditional gender lines. For example, men were about twice as likely to identify adventure as a dream theme (16 percent versus 9 percent) and more likely than women to speak of fame, wealth and power (15 percent versus 11 percent). In contrast, women were nearly twice as likely as men to identify family as a dream theme – especially as family pertained to motherhood and family unity (18 percent versus 10 percent) and more heavily focused on appearance in line with gender socialization.

Women were more likely to say they never give up on their dreams (74 percent versus 63 percent) and believe their dreams were realistic (86 percent versus 63 percent). About two-thirds of women felt there was a 70 percent chance or greater that their dreams would come true while only 48 percent of men felt that way. Both groups said dreaming was important, but women were more adamant, with 93 percent of women advocating dreaming versus 77 percent of men.

Latinxs Are Less Optimistic

Most people from all of the racial groups felt their dreams were realistic and achievable. More than two-thirds of Asian, Black, multiracial and white respondents thought they had a 70 percent chance or better of accomplishing their dreams.

But Latinx respondents were less positive on these issues. Slightly more than half saw their dreams as realistic while only 41 percent felt there was a 70 percent chance or higher that their dreams would come true. Latinx respondents were more likely than any White, Black and Asian to voice negative cultural lessons on dreaming such as believing it is pointless because “the deck is stacked and the system is rigged.”

The American Dream

Cerulo and Ruane studied how dreams are represented in U.S. popular culture, identified positive and negative lessons on dreaming, and used data to report on people’s dreams at various moments in time.

Survey data found four times as many Americans showed optimism about the nation’s future versus pessimism, while 82 percent of Americans said their “American Dream” has already been achieved or was in reach. Sixty-seven percent of national polls respondents said they were optimistic about their personal futures. Even among minority groups, who are most likely to face structural disadvantages as they work toward achieving their dreams, optimism ran high—sometimes higher than it did among Whites.

Cerulo says American culture encourages people to dream big. However, it’s important to ground those dreams with a dose of reality.

“When teachers say, “You can be anything you want, even president of the United States,” and don’t explain the way in which politics, money and power are intertwined, they lay the groundwork for feelings of personal failure and resentment,” she said.

Studying dreams provides a new avenue for better understanding inequality that precedes action or outcome.

The researchers said lifting the burdens of inequality is what will truly help make Jiminy Cricket’s promise true for all people and not just some people.