Christian Lambertsen: The Rutgers Alumnus Who Was a Father of SCUBA Diving

His invention helped win World War II

'From the way he told it to me, he very nearly drowned during his initial experiments. He was getting trapped underwater in the first contraption he designed.'- Aron Fisher

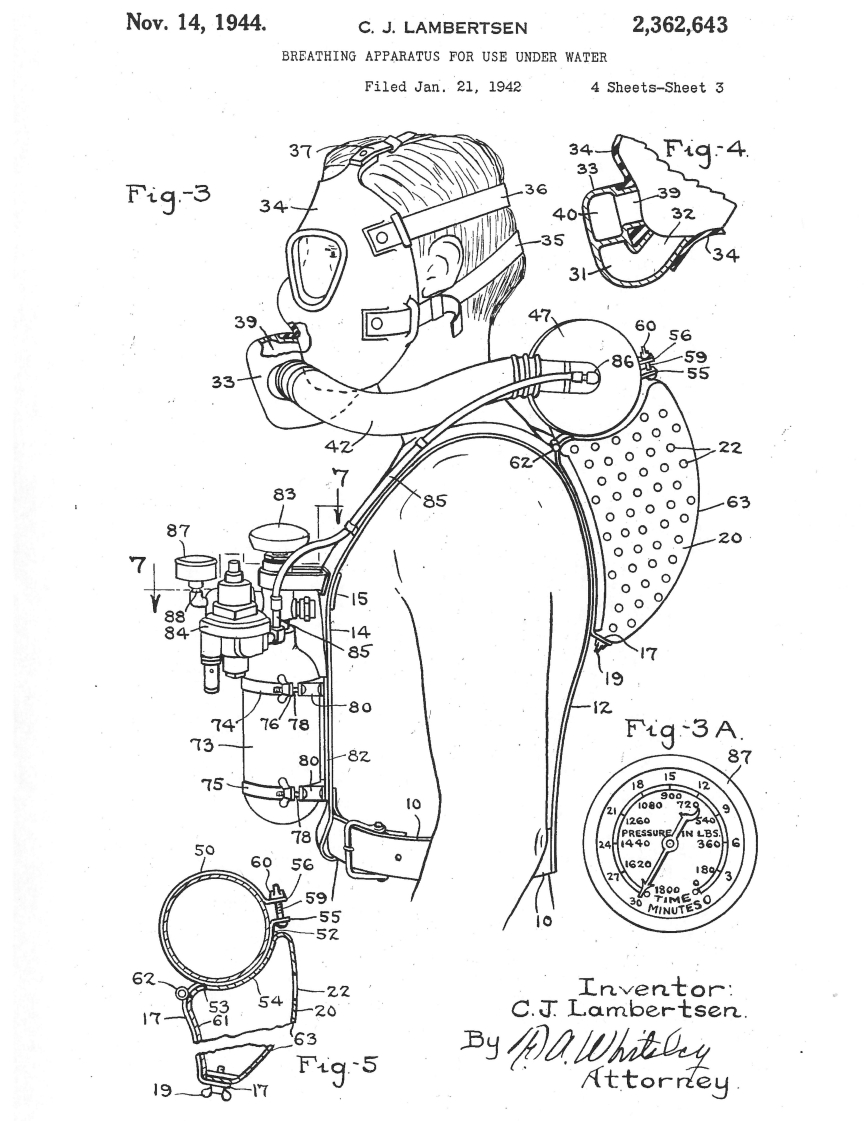

Human beings do not have gills, but swimming underwater as if we did has long been a dream. With his “amphibious respirator unit,” a prototype for what the world now calls scuba gear, Christian Lambertsen, made diving feasible for millions of people.

He also helped win a war.

When Lambertsen was a teenager, exploring the deep already fascinated him. He liked to dive in Barnegat Bay, where a cousin sitting in a rowboat would use a bicycle pump and hose to send him air. That primitive but innovative breathing apparatus planted a seed that Lambertsen would later cultivate.

After earning a degree in biology in 1939 at Rutgers in New Brunswick, Lambertsen entered medical school at the University of Pennsylvania—just as Hitler’s armies were beginning to overrun much of Europe. As the Free World built its defenses, Lambertsen realized that allied navies would be much more effective if their divers could enter enemy-held waters undetected—to gather intelligence, booby-trap hostile ships, or otherwise disrupt operations.

In the late 1930s, U.S. Navy divers could not do that. Even if they had breathing equipment that let them swim and dive without being tethered to ships, carbon dioxide bubbles would rise to the surface each time they exhaled, making it easy for the enemy to spot them.

Lambertsen would solve that problem by adapting technology from the anesthesia equipment he used as a medical student. During surgery, physicians mix an anesthetic gas with air drawn from the atmosphere using equipment that makes the mixture more breathable and effective by “scrubbing out” much of the carbon dioxide (CO2) that forms during respiration. Lambertsen imagined that similar “scrubbers” could help eliminate CO2 bubbles in war situations and went to work perfecting his idea with an apparatus that he would both design and test underwater himself.

“From the way he told it to me, he very nearly drowned during his initial experiments,” recalls Aron Fisher, a professor of physiology at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school who was a student of Lambertsen’s at Penn and then a longtime faculty colleague. “He was getting trapped underwater in the first contraption he designed.”

Soon enough, Lambertsen worked out the design kinks, and his system progressed to the point where divers could both inhale and exhale smoothly without a trace. He first presented his idea to the Navy, which rejected it. But the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the precursor to today’s Central Intelligence Agency, realized what he had and put Lambertsen and his invention to work as part of the effort to win World War II.

Lambertsen took charge of training OSS divers, was deployed with them to Burma, and would later receive the Legion of Merit for the success of their covert missions. “He is now known as the forerunner of the Navy SEALS,” Fisher notes.

Once the war was won, and there was no more need for military secrecy, Lambertsen’s invention—which by then had earned the first of his 11 patents—became available to all. It is widely believed that Lambertsen coined the term “scuba” (for “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus”), and now millions of registered scuba divers are able to explore the wonders of aquatic life with the same ability not to disturb their surroundings as the military enjoyed during the war.

The benefits of Lambertsen’s expertise—and further research he would conduct for decades while on Penn’s medical faculty—stretch far beyond the deep to the heavens and to many earthbound medical settings. He served on NASA panels during the early years of space flight, working to make astronauts’ breathing systems safer. He also became a leader in developing hyperbaric oxygen therapy, widely used as a treatment for the diving-related disorder known as the bends—where rapid changes in water and air pressure can cause severe sickness or death—as well as more recent applications such as the treatment of hospital patients with wounds that do not heal.

After Lambertsen died in 2011, at age 93, members of the intelligence, military, and recreational communities were all present as his ashes were scattered on the waters off Key West—honoring a man whose vision had revolutionized humankind’s relationship with the undersea world.