Art in Digital Age: Philosophers, Scientists, Artists Discuss Technological Advancements in Art

From AI and robots to digital ethics, Rutgers researchers discuss high-tech trends in art

"What I appreciate about dimensionism is there is a large community of people working on the boundaries of their disciplines, creating new kinds of art and technology and new experiences for us" - Elizabeth Demaray

What are you actually getting from technology and what is it doing for your life? Can artificial intelligence replace artists and reconfigure what we view as art? Can art be used as a tool to combat social and environmental issues?

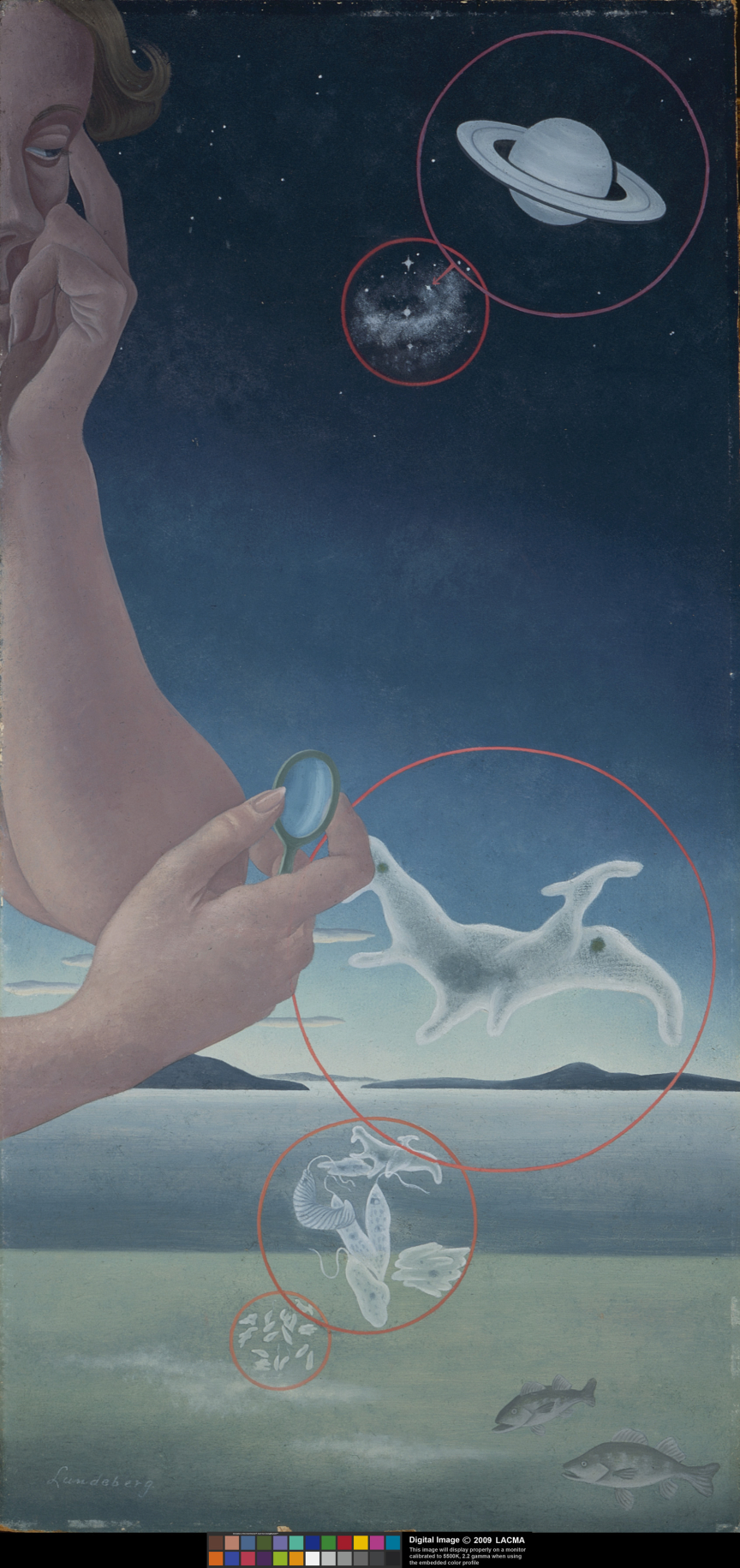

Inspired by the Zimmerli Art Museum’s Dimensionism: Modern Art in the Age of Einstein exhibit, Rutgers scholars in philosophy, mathematics, computer science, engineering and other disciplines recently posed these questions during Interdisciplinary Dimensions: A Rutgers Symposium. The event was part of an ongoing series of seminars by Rutgers physicists, engineers, astronomers and other faculty on the nexus between art and science.

“In the beginning of the 1930s, Hungarian poet Charles Sirató drafted the Dimensionist Manifesto, which called for artists to embrace the spirit of scientific innovation. He and others sat down to discuss what was important to them, and didn’t focus on the links of science and art but rather on the larger issues and incorporated science and art into the discussion. That's what we hope to replicate through these ongoing discussions,” said Thomas Sokolowski, director of the Zimmerli.

During her presentation, Elizabeth Demaray, an associate professor of art at Rutgers–Camden, discussed her IndaPlant Project, which originated as a which originated as a collaboration with Professor Qingze Zou from the School of Engineering at Rutgers–New Brunswick, Ahmed Elgammal from the Department of Computer Science at Rutgers–New Brunswick, and Simion Kotchoni, a professor of biology from Rutgers–Camden. The project, which began five years ago, was designed to let potted houseplants move by themselves to places where sunlight and water are available. The part robot, part houseplant -- dubbed the “floraborg” -- is moving into its next phase, which will combine GPS and driving technology so an endangered plant species can travel to better conditions.

Demaray hopes the new series of floraborgs, known as “the navigators,” will address the effects of climate change and air pollution on the extinction of many plant and animal species.

“We are in the midst of a massive species die-off. The Earth is losing 280 species a day and we don’t know what their capabilities are. While this project only pertains to regular houseplants, we hope that it will support research into a cyber physical system that may allow us to better understand plant signaling. This may also allow us to understand the unique capabilities of plant species before they go extinct,” said Demaray.

She said that although she studied cognitive psychology and neuroscience in college, it was her first art sculpture during her junior year that ignited her career in art. “Art allows you to say things that can't be simply stated. What I appreciate about dimensionism is there is a large community of people working on the boundaries of their disciplines, creating new kinds of art and technology and new experiences for us. In our historic moment, it is a good platform to grapple with issues, questioning the nature of what future lifeforms would be like.”

Working alongside Demaray on her floraborg project, Elgammal, director of the Art & Artificial Intelligence Lab, has also conducted research on a new trend of computer-generated art. Using AI, Elgammal was able to train a computer to both recognize and curate art images from the past 500 years. By using generative adversarial networks, the computer created its own original artwork, which when tested by an audience was indistinguishable from art created by human artists. While AI-generated art has raised ethical questions on whether machines can replace artists, Elgammal said the fear is no different than other technological advancements in other fields.

“When you think about the viewpoint of photography when it first came out, it changed our point of view of what art can be. Now that AI is central to our life, it is becoming a part of the medium that artists are using,” said Elgammal, whose research on AI-generated art appeared on a PBS segment and was awarded an Emmy in 2016. “I am not saying that the machine making art autonomously means the art is beautiful. There is always an artist behind the machine. Then it becomes more conceptual, and the artist is always at the center of the image creation.”

At the core of advancements in art and science, Alex Guerrero, a professor of philosophy at Rutgers–New Brunswick, said it’s important to always ask “should we do this?”because the ultimate goal of innovation is the betterment of humanity.

“Technology and philosophical changes interact. Our sense of who we are affects the kind of technology we design and build whether it is solar powered electric fences or video calls. But we should be mindful of questions such as ‘should we do this?’ and ‘who will it help and who might it harm?’ and ultimately ‘what are you actually getting from technology and what is it doing for your life?’”

The next program in the Dimensionism series will be “Charles Sirató’s Journey to the Dimensionist Manifesto and Beyond" by art historian Oliver A. I. Botar on Oct. 15 at Murray Hall.