Visually Impaired Pianist Thrives With Support From Mason Gross

Process developed by Rutgers to transcribe music to braille for prodigy Yerko Difonis opens door for other musicians with disabilities

Yerko Difonis, 28, is not the first musical prodigy born blind and partially deaf.

However, he is the first student with those disabilities to pursue a master of music degree in piano performance at Mason Gross School of the Arts (MGSA).

“God took away two of the main senses you need for music but gave him this incredible talent,” said his piano professor, Karina Bruk. “He is a virtuoso.”

Before the Chilean immigrant could enroll in Rutgers-New Brunswick this past fall, the university’s Office of Access and Disability Resources was asked to find a timely and economical way to transcribe his complex musical scores into braille – during a pandemic.

“You look at all that sheet music and it’s well beyond what most people do. It was like a foreign language to us when we first started,” said Jason Khurdan, manager of central services for the office.

Now, a year after Difonis registered for MGSA, Rutgers’ disability resources office has fine-tuned a cost-effective and comparatively fast process for transcribing music scores to braille, making Rutgers one of the few universities in the country to offer this service to visually impaired music students.

“We’ve spoken with a lot of other universities with blind students in their music programs and almost none are providing this level of braille music,” said Khurdan. “Often times these students are dependent. They are learning by ear and develop a knack for memorizing it. A lot of them just make do. For some of them that may work, but it’s not equal access.”

That is how Difonis learned to play.

“I was 2 years old in the crib, and everyone would notice I would nod my head when they put music on,” said Difonis, who began playing the keyboard from memory as a 6-year-old.

He was born with retinitis pigmentosa, a condition that blocks the brain’s ability to send signals to the eye. The cause of Difonis’s irreversible hearing loss is unknown but his external digital hearing aids make playing possible.

Difonis’s family emigrated to the United States in 2000 on a temporary visa in search of educational resources for their son. They lived in New Jersey, then Brooklyn, N.Y., and finally Staten Island, N.Y. While in Brooklyn, they were connected with Lighthouse International, now Lighthouse Guild, where he was a member of the children’s program. Difonis learned Braille and enrolled in the Filomen M. D’Agostino Greenberg Music School for those with vision loss.

As a child, Difonis amazed local audiences with his ability to play classical piano pieces from memory, performing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and attending LaGuardia High School of Music and Art and Performing Arts. Then, in 2010, Difonis and his family were forced to return to Chile under threat of deportation for remaining in the U.S. on an expired visa.

Back in Chile, he took private lessons with Chilean pianist Roberto Bravo while finishing high school, and continued to wow audiences with his performances, including on the televised talent show “Talento Chileno.” Difonis advanced his conservatory training with Mario Cervantes at the Sergei Prokofiev Conservatory in Viña del Mar while working toward his BA in English pedagogy from the University of Playa Ancha in Valparaíso.

As Difonis’s repertoire expanded, tracking down braille versions of the scores he sought to perfect became more cumbersome.

“If I needed to study a more modern piece, it was very irksome,” he said. “I would request them, but not all the pieces were available. If they were, I had to wait at least two months after a request to receive it.”

Needing to access resources outside of Chile that would allow his talents to flourish, Difonis came to New Brunswick in February 2020 for his MGSA audition just weeks before the state shut down and the university shifted to remote learning. With a student visa in hand, he moved into his on-campus apartment on Sept. 1 and started remote instruction with Bruk.

“The pieces he plays are masterworks. Any sighted pianist would take years to master them, and he plays them with complete understanding,” said Bruk, who insists that this would not be possible if his music was not transcribed in braille.

Weeks before each semester, assistive technology specialist Cyndi Cartagena connects with Difonis’s graduate adviser to identify courses and instructors. She assesses his course materials, including a combination of music scores and online text, and works with disability resources teams from around the country to convert anything that cannot be accessed by his laptop’s screen reader.

Transcribing multi-movement scores required working with new people, said Khurdan, including Heidi Lehmann, founder of Bach to Braille Inc., and MGSA graduate composing student Anthony Petruccello. Working from his home in Waldwick, Petruccello takes a PDF copy of a score and manually recreates it in a musical notation program called Sibelius – making sure each of the composer's marks, symbols and notations can be accurately reflected on the braille score.

“Some 20th-century music is very visual. They dispense with certain traditional musical notation that requires interpretation for the braille transcription,” said Petruccello, 25, who plays classical guitar and earned his BA in music studies from William Paterson. “Sometimes composers notate something visually, like the distance between two notes that don’t have exact rhythmic values, but if you’re blind it’s useless. We have to reinterpret it like a performer would and express that in the braille.”

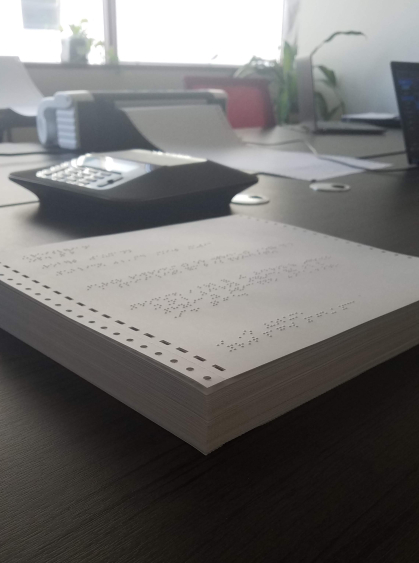

It is then fed into BrailleMuse, a free online tool hosted by Yokohama University in Japan and printed in braille before a physical copy of the music is sent to Difonis to study.

“The work they’ve done chops down barriers,” said Cartagena. “We were told it would take three to six months to convert some scores, but Yerko has everything he needs to be on pace with the rest of his class. We are hoping the word gets out to other visually impaired musicians and that Rutgers becomes known for what we can offer them.”

Until then, Difonis is appreciative of all the assistance he has received at Rutgers, which puts him that much closer to achieving his dream of becoming a concert pianist or performance professor.

"They’ve been a great help to me. Nothing beats a human transcriber,” he said. “This is expanding my ability to play other styles of music that I didn't have access to before.”