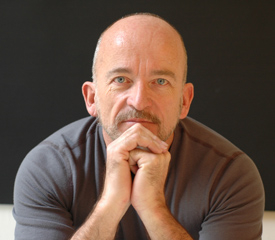

For award-winning Rutgers professor, poetry is more than a craft

Those connections have won him such prestigious literary honors as the National Book Critics Circle Award, the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction, the “His syntactically complex and aesthetically profound free verse poems, odes to urban gay life, and quietly brutal elegies to his lover, Wally Roberts, have been hailed as some of the most original and arresting poetry written today.” – The Poetry Foundation, publisher of Poetry Magazine.

Mark Doty waxes, well, poetic, when he talks about the craft that has both nurtured and been nurtured by him.

And why not? It’s been a mutually rewarding relationship, spanning four decades and producing national awards and interviews in every journal known to literary mankind, not to mention accolades from a mainstream media that has not traditionally been generous with its coverage of the genre.

“I started writing poetry – serious poetry – in high school. I had the sense that this was the thing without which I would not be myself,” says the Rutgers English professor, who will return to the School of Arts and Sciences this fall after a brief hiatus.

Faced with unbridled joy at the antics of his beloved retrievers, or with grief over a partner’s relentless descent into illness, Doty turns to words to define the world, both for himself and for his audience. Acknowledging that writing is essentially a solitary activity, he says he is always aware of the person who will ultimately be on the receiving end his work.

“I think of my poems as addressing an empty chair in front of me in which a reader is invited to sit,” he says. “The poet’s art is making connections.”

Those connections have won him such prestigious literary honors as the National Book Critics Circle Award, the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for First Nonfiction, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and a Whiting Writers Award. In 1995, he became the first American to win Great Britain’s T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry; more recently, the American Library Association honored him with its Stonewall Book Award for Non-Fiction for Dog Years: A Memoir, which chronicles his life with two rambunctious but noble dogs.

“Elegant, plain-spoken, and unflinching, Mark Doty’s poems in Fire to Fire gently invite us to share their ferocious compassion. In this generous retrospective volume, a gifted young poet has become a master.” – From National Book Foundation on winning its 2008 award

The army engineer’s son from Tennessee published his first book of poetry, Turtle, Swan, in 1987, the year after the first panel was sewn for the AIDS quilt and the U.S. death toll from the epidemic stood at just over 4,000. When Wally Roberts lost his battle in 1994, the fatalities had risen to 41,920, and for the first time Mark Doty knew the architecture of poetry could no longer accommodate his emotions.

“A poem needs to be a taut, dynamic vessel, and I couldn’t do that when Wally died,” he says today. So he turned to another form, memoir, recounting in Heaven’s Coast the final months and weeks the two men shared. “Non-fiction prose made a kind of container for my grief,” he says, at the same time opening the writer to unexplored literary terrain.

Today he easily travels back and forth – “I’m ambidextrous,” he observes – and is juggling two simultaneous projects: a nonfiction book about reading Walt Whitman and finding connections with the 19th-century humanist across time, and a volume of poetry based on his own life as a gardener in Long Island and the process of putting down roots: “in essence, shaping a landscape and making a self.”

Recently, Doty shared with followers of his blog his struggle with vision and balance following a detached retina and three surgical procedures to correct it; another is scheduled. Today, he recalls that one of the most unsettling aspects of last winter’s experience – which limited not only his ability to travel, but also, horrors!, to read – was that it left his very perception unstable.

“And as a poet, I use vision the most of all my senses,” Doty says. “And so I asked myself the metaphorical question: Maybe I was not seeing ‘right’ all along? …”

The critics would argue otherwise. And have, over the course of eight collections of poetry, four non-fiction prose books, and a brief handbook for writers.

“Doty’s facility with his chosen form … is so natural that the craft in his work is all but invisible; he makes the damnably difficult look deceptively simple.” – Kevin Nance, Booklist