#Striketober Becomes #Strikesgiving

From nurses to factory workers, thousands of Americans are on strike at the same time as a nationwide labor shortage is giving workers more bargaining power

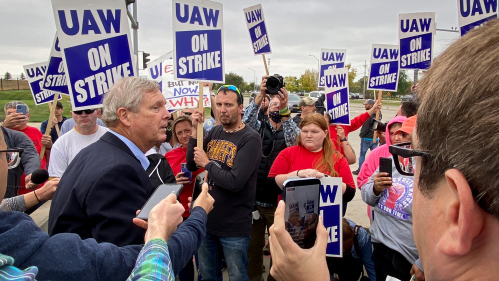

More than 10,000 John Deere workers walked off the job in October, demanding higher pay and better benefits at a time when their employer is enjoying record profits. About 2,000 Catholic Health hospital workers are on strike over staffing and wages. And 1,400 Kellogg’s workers are still on the picket line to push back against a two-tiered pension system.

The nationwide surge in strike activity peaked at 17,000 workers across a wide range of industries, and it could have been even bigger. The unions representing Hollywood crew workers and Philadelphia mass transit employees reached eleventh-hour agreements to prevent work stoppages. Negotiations are continuing in other workplaces, including a large, multi-state healthcare system.

It’s all happening against the backdrop of a rise in union organizing activity and a nationwide labor shortage that’s giving workers more bargaining power. As the calendar turns from #Striketober to #Strikesgiving, Rutgers Today asked Naomi R Williams, a labor historian in the School of Management and Labor Relations, to put it all in perspective.

Why are so many workers on strike right now – and how does the labor shortage affect their decision to walk?

The pandemic and the resulting economic crisis put more workers into difficult situations. Now, companies are bringing in huge profits and top managers are seeing rewards in terms of bonuses and incentive payments. Yet, workers are still laboring long hours under difficult to harsh conditions.

Workers are beginning to feel like now is the opportunity to leverage their collective power to demand better working conditions, more dignity at work, and a fairer share of the profits from their labor. They also realize that they can regain some of the protections they have lost through poor enforcement of our current labor law.

We saw a wave of teacher strikes a few years ago, but when was the last time we saw so many workers in so many different industries walk off the job?

It’s been more than 50 years. Changes to the labor law in 1947 made it harder for workers to organize into unions and collectively use their power. A hostile political climate didn’t help, either. But over the last four years, we have seen workers gaining momentum through work stoppages and other actions. I think the teacher strikes served as a catalyst, as well as the slow recovery (for workers) from the 2008 financial crisis and now the pandemic.

Are we seeing any changes in strike demographics? For instance, are we seeing more young people and people of color taking a leading role in collective action at work?

I think the role of young people and people of color is more visible now, but not new. Many people look to what they consider the heyday of the mid-20th century and workers in industrial settings and their strike activity. Many workers of color were denied entry into those positions until the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, they were active in public sector, agricultural, and service sector positions. And those in industrial unions were often dedicated members. In fact, workers of color are more likely to join unions than white workers, when given the opportunity.

What do you think will happen next? Do you expect the wave of strikes to continue or do you think things will settle down?

I think we have been building to something big over the last decade or so. Really, since the Occupy movement, more and more working people are recognizing that they do not receive a fair share of the profits or wealth. Workers have been motivating and inspiring each other to action. They are seeing the benefit of working collaboratively, especially as the tight labor market and political and social climate have tilted in their direction.

It reminds me of Paul Whiteside, a worker who participated in strikes in the 50’s and 60’s and became a labor leader. He was interviewed in 1981 and said, “When you got control of a thing, you got the majority in an area, you tend to be more aggressive."

And that is what we are seeing now. Workers who have been trying to negotiate with employers are taking the step to authorize and then go out on strike, because they feel now is the time to leverage their power.