Scientists Discover How the Body Fights Viruses That Try to Evade the Immune System Response

Immunologists from Rutgers University and Weill Cornell Medicine unveil a new path the body uses to fight viral infections

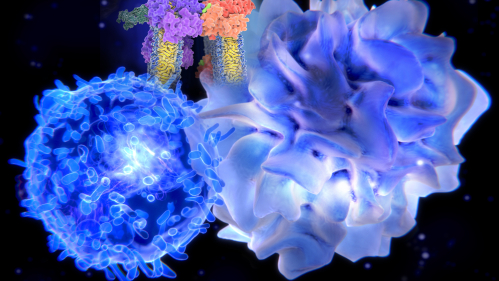

Scientists have discovered a molecular pathway that counteracts the ability of some viruses to evade the immune response – raising hope of improving the body’s ability to fight off viral infections, such as COVID-19, and cancers, which also develop strategies to evade immune recognition.

The study, published in Nature Immunology by researchers at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School’s Child Health Institute of New Jersey and the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine, uncovered why some viruses are recognized and eliminated by the immune system despite viral strategies to escape recognition.

The goal of the immune system is to recognize and eliminate viruses and other pathogens before they cause disease. In the constant battle between viruses and their hosts, viruses often develop ways to thwart the immune response then replicate successfully and result in illness. This is particularly true in viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, for which many people may be infected but never become sick, or herpes viruses, which may establish latent, or quiet, states of infection.

The study identified a new route that cell proteins that are involved in recognizing viruses take to still recognize foreign viral proteins even if the virus is trying evade the immune response. This pathway is functional in cells that alert the immune system to infections and plays a role in determining if the immune system will react to cancer.

Gaëtan Barbet, an immunologist and newly recruited assistant professor at the medical school’s Child Health Institute, has spent the past 16 years studying the biology of cells responsible for how the immune system reacts. He is investigating how these cells shape the immune responses in parts of the body that produce mucus like the lungs and gut.

Barbet, who conducted this work with principal investigator Julie Magarian Blander, the Gladys and Roland Harriman Professor of Immunology in Medicine at the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at Weill Cornell Medicine, and Priyanka Nair-Gupta, a former doctoral student in Blander’s lab, says that the results indicate that immune systems take alternative routes to recognize viruses.

“Some patients with an immunodeficiency disorder called Bare Lymphocyte Syndrome (BLS) have mutations in proteins, such as TAP, the transporter associated with antigen presentation, which is involved in recognizing viruses and other pathogens,” Barbet says. “This could explain why some patients who have mutations in TAP are no more susceptible to viral infections than the rest of the population.”

“The idea of developing TAP-independent responses raises hope for multiple human diseases, including cancer where MHC-I antigen-presenting functions often altered in tumor cells to evade the immune system,” adds Blander, who is an expert on innate immunity and inflammation. “Ultimately, we want to understand how to manipulate this TAP-independent response in order to better enhance anti-viral or anti-cancer responses or to better design vaccine strategies.”

The team’s research was supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. Other investigators include colleagues from Weill Cornell Medicine; the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; New York University; and Goethe University, Frankfurt, Germany.