Shatima Jones’s urban ethnographic research was inspired by Obama campaign strategy

If a “black community” exists, where exactly would one find it?

For the past three years, Shatima Jones, a doctoral candidate in Rutgers’ Department of Sociology, has conducted ethnographic research in a black barbershop in Brooklyn, New York, to examine how racial solidarity is (or isn’t) achieved in everyday life.

“The term ‘black community’ is everywhere – pop culture, media – but race alone may not always be enough to create community,” says Jones, a graduate assistant at the Center for Race and Ethnicity who studies the intersection of social interaction, community formation, and race relations.

Though churches have historically been recognized as central to the lives of African Americans, Jones sought ways to challenge her own preconceptions and societal assumptions about the black community through research in more secular spaces.

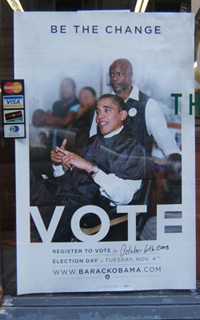

The Brooklyn native, who received undergraduate and master’s degrees in sociology from Hunter College and Rutgers, respectively, began to home in on barbershop research during Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign.

The campaign saw these shops as places where dialogue about critical social and political issues occurs, and staff and volunteers began to canvas black barbershops and hair salons in a targeted outreach initiative to maximize African-American voter turnout.

Obama’s grassroots voter mobilization program resonated with Jones, who has frequented the same Brooklyn hair salon since the age of 7 and considers the shop a social hub.

“Hair salons are definitely spaces where women gossip about any and everything,” she says. “I have a personal relationship with my stylist – we discuss serious topics and not-so-serious topics.”

Jones wondered if similar social interaction occurred in black barbershops and set out to uncover whether and how racial solidarity is created among barbers and their clients.

In an economic climate in which businesses turn over rather quickly, Jones selected a barbershop in a predominately black, working class Brooklyn neighborhood with a constant flow of customers. She conducts her field research three to four times a week at varying times of day for four to five hours at a time.

Amid the political and sports talk, Jones describes the barbershop as a sort of "backstage" where black men constantly negotiate the best way to present themselves in the context of how others perceive them in the outside world.

“Getting a haircut is part of managing your front, your physical presentation,” Jones says. “If the men look unkempt, they do not feel respectable at work, in the street, or elsewhere.”

The barbers also informally, yet actively, mentor and encourage younger customers to not only maintain a respectable appearance but to also build respectable character. According to Jones, even older customers admonish younger men to ‘Get a job,’ ‘Be an active father,’ and ‘Respect your mother.’

Jones’s research supports her in-progress dissertation, “Doing Race and Shaping Community in the Black Barbershop.” As an ethnographer, she does not initiate conversation with the barbers and their customers, but tries to keep her presence to a minimum while taking copious field notes of the social interactions between the shop’s six barbers and their customers of all ages.

“I don’t think the barbers realized there would be three years of observation,” she says, “but they are proud that I’m pursuing higher education and were also pleased someone found them interesting enough to study.”