Ceramic expertise earns university a $9 million role in Army-funded research group at Johns Hopkins University

Rutgers’ longstanding expertise in ceramic engineering is being tapped by the military to develop armor that better shields soldiers from modern-day battlefield threats – most notably from IEDs (improvised explosive devices).

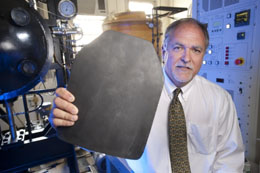

Richard Haber, professor of materials science and engineering, oversees the Rutgers component that is slated to receive up to $9 million. He says the effort will bring a more scientific approach to armor development than has been done in the past. This involves examining potential materials down to the atomic level and modeling their performance with computers.

“When you look at all the pieces of armor a soldier wears, before you know it a soldier is carrying 60 to 80 pounds of armor,” said Haber. The Army would like to cut that weight, but “the bad guys are constantly coming up with new and innovative ways to kill a warfighter.”

Armor behaves differently under different threats, he added, and armor that protected Vietnam-era soldiers from a bullet might not adequately shield Middle Eastern soldiers from a shower of nails packed in a roadside bomb.

The consortium is going to explore a range of materials that show promise for being lightweight and tough, including metals, plastics and ceramics. Rutgers will focus on ceramics, applying managerial and technical expertise gained during the past decade through the school’s Ceramic, Composite and Optical Materials Center (CCOMC). The center, originally funded by the National Science Foundation, cultivated industrial partnerships that brought in further funding as well as expertise on translating research into manufacturing technology. Haber, the center’s director, says the Army-funded effort will benefit from these same relationships with their private funding opportunities.

Armor’s function is to shield personnel and vehicles from the fast, high-pressure impacts of bullets, shrapnel and other projectiles. To do that, armor material has to bend, stretch or compress when struck to absorb the projectile’s energy. But it can’t break or shatter. With today’s threats, it also has to withstand repeated hits. Some materials can absorb one impact, and then having been weakened, may fail on subsequent hits.

“Modeling armor materials will be an essential part of our research,” said Haber, who characterizes past efforts as “make it and shoot it.”

“Testing is getting very expensive,” he said. “It’s difficult to test armor on tanks and soldiers. We have to be able to measure responses, but some of these events happen so fast that it’s difficult to measure.”

One material that Haber is investigating is boron carbide. It’s a tough but lightweight ceramic that is 30 percent less dense than existing armor, but it fails catastrophically under high-pressure impacts. “If we can redesign the compound’s atomic crystal structure and learn to manufacture it, it could revolutionize tomorrow’s armor.”

Haber notes that the consortium’s work is not classified.

“This is open research, and we can publish it,” he said. “Our work is about saving lives, and the results will trickle down to others who can benefit, such as police.”

Haber expects the funding to support as many as six graduate students, six postdoctoral researchers and research faculty, and several undergraduate students. The researchers will have access to the Army’s advanced research facilities, including those at its well-known Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.

Media Contact: Robin Lally

732-932-7084, ext. 652

E-mail: rlally@ur.rutgers.edu