Working with mesothelioma patients becomes eye-opening experience in more ways than one

Abby Shulman Palmer spends her days and many of her nights advocating for patients with mesothelioma: answering questions about clinical trials, advising on conventional and alternative treatments, and offering a sympathetic ear.

But soon after starting her job as a social worker with the Mesothelioma Alliance about a year and a half ago, the Rutgers alumna – psychology major, Class of 1976 – stumbled across some unexpected answers of her own, answers to a medical mystery that had surrounded her family for more than a quarter of a century.

“When my dad got sick and then died at the age of 69, the doctors couldn’t quite figure out what he had. That was 27 years ago,” Palmer says. Once she began sifting through the literature about mesothelioma, she started putting the pieces of the puzzle together.

Mesothelioma – a disease that attacks the protective lining of the body’s organs, most often the lungs or those in the abdominal sac – has been strongly linked with asbestos, especially among workers who inhaled it or absorbed it through their skin over extended periods.

During the last century, the product was commonly used in thousands of applications, Palmer says, from brake pads to artificial snow.

“If you were born in a certain era, it was everywhere – even in the schools. It was considered to be this miracle fiber which could make things stronger, make them fireproof. You saw it in acoustical panels, adhesives, sound-proofing, insulation, spackle, textiles and vinyl tiles – even in potting soil.”

The U.S. military also found valuable uses for asbestos. And here’s where the story took a personal turn for Palmer.

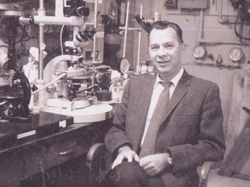

“When I began reading in preparation for the job, I learned that the Brooklyn Navy Yard was a hot bed for asbestos,” she says. “During World War II, my father was a physicist working with a team to develop degaussing procedures for U.S. military ships to prevent them from being blown up when they go over mines.

“I knew that my father had done that work, and that it was something to be really proud of.”

But it was also, Palmer would come to understand, something to that might have had unforeseen and ultimately fatal results.

As knowledge began to accumulate about the deadly effects of asbestos, which frequently did not manifest themselves for 30 to 50 years, the medical world definitively linked the now-limited contaminant with mesothelioma.

But in 1985, when Palmer’s father began experiencing pain and complaining of feeling ill, such research was still relatively young; only four years earlier had the U.S. government requested information from American manufacturers about asbestos use in their products.

Moreover, the issue had become shrouded in controversy when corporations initially covered up such use for fear of damaging their own bottom lines. Palmer notes there was evidence that manufacturers knew about the health hazards as far back as the 1930 -- when the first suspicions about its use surfaced -- but kept the information hidden.

“When my dad died, all we knew was that it was cancer, and that it had spread, but the doctors never figured out the primary site,” says Palmer, a native of Rockaway now living in Wake Forest, North Carolina. “When I talked with my mother and sister about the possibility that it was mesothelioma, they said, ‘Wow that certainly is a possibility.’ ”

Today, more than 2,000 new cases of mesothelioma are diagnosed in the United States every year, according to the Mesothelioma Alliance. There is evidence that family members and others living with asbestos workers are at increased risk.

Many of these patients wind up on the other end of Abby Palmer’s phone line.

Founded about a dozen years ago by patients and their families frustrated by a lack of information available to them, the organization is under the auspices of Cancer Monthly, which publishes the book Surviving Mesothelioma: A Patient’ Guide by Paul Kraus.

Palmer is one of a handful of full-time and part-time staffers, charged with keeping abreast of the latest treatments and approaches.

“People call with a lot of fear, a lot of shock. We help them track down the top doctors in the field – for instance, if you live in the middle of Iowa, chances are you won’t be near a specialist who can treat you. So I’m talking to people all over the country, sometimes all over the world,” Palmer says.

A member of the first coeducational class on the main Rutgers campus in New Brunswick, Palmer brings more than 30 years of medical social work experience to her patients.

After receiving a master’s degree in social work from the University of Wisconsin, she worked for general hospitals, rehabilitation facilities and Planned Parenthood. For many years she was an independent contractor for Visiting Nurse and Homecare Northwest Connecticut, where she was a founding member of the hospice team.

Palmer acknowledges that despite her new-found understanding of mesothelioma, she may never be 100 percent certain about her father’s fate. But even so, she feels comforted by the possibility.

“In some ways, it helps me understand my genetics better,” she says. “If, in fact, if it was mesothelioma caused by asbestos, that means I don’t necessarily have a predisposition to cancer. I always had to be vague when doctors asked me about my medical history, but now I can put this out there as a possibility.”

Callers can reach Abby Palmer of the Mesothelioma Alliance at 1-619-261-7922.