Methadone Use in Early Pregnancy May Lead to More Birth Defects Than Buprenorphine

Researchers from Rutgers Health and Harvard Medical School have found fewer congenital defects in children whose mothers treated opioid use disorder with buprenorphine rather than methadone during the first trimester of pregnancy.

The study findings extend those from a previous study from the same research group, which found fewer preterm births and fewer incidences of withdrawal symptoms in the children of buprenorphine users compared to methadone.

The study authors said the findings support the use of buprenorphine in pregnancy as a first treatment option for many patients. The findings do not, however, justify a switch from methadone to buprenorphine during pregnancy, which would entail an added risk of side effects and relapse.

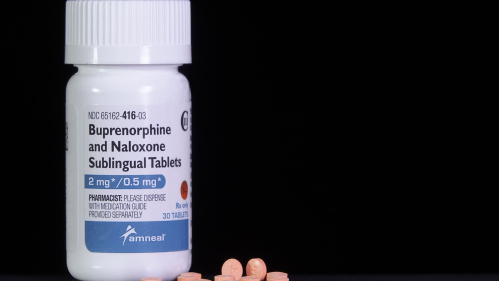

“There have long been questions about which of these two medications is better in pregnancy,” said Elizabeth Suarez, a pharmacoepidemiologist at the Rutgers Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research and lead author of the study. “Methadone has been the traditional choice, but there’s been a steady shift to buprenorphine since it arrived in 2003. Both are recommended in standards of care, and there hasn’t been a lot of data to choose between them.”

Although the study identifies a potential advantage for buprenorphine, its authors emphasized that their findings do not mean that buprenorphine should always be preferred to methadone, though one of the two treatments is always preferred to leaving opioid use disorder untreated.

“The treatment choice for opioid use disorder is very complex and nuanced, especially in pregnancy,” Suarez said. “If you are already stably controlled on methadone prior to pregnancy, it's not recommended that you switch because of these findings because buprenorphine just doesn't always work as well for patients, and switching medications adds risks. This is just one piece of the puzzle in terms of trying to think about which medication to use.”

The study used Medicaid utilization data that spanned the entirety of 13,360 pregnancies plus one month after delivery. Researchers connected parental records with corresponding newborn records to see how the use of either buprenorphine or methadone was associated with congenital malformations ranging from major organ defects to clubfoot and oral clefts.

The overall risk of malformations was 50.9 per 1,000 for the 9,514 pregnancies with first-trimester buprenorphine exposure and 60.6 per 1,000 for the 3,846 pregnancies with methadone exposure.

After the researchers adjusted figures to account for differences between buprenorphine and methadone users, buprenorphine use was associated with an 18 percent lower risk of all malformations, a 37 percent lower risk of cardiac malformations, a 45 percent lower risk of clubfoot and a 46 percent lower risk of oral cleft.

In secondary analyses, buprenorphine was associated with a decreased risk of central nervous system, urinary and limb malformations but a greater risk of gastrointestinal malformations.

The study team was able to find associations not just between the medications and all congenital malformations but also between the medications and specific types of malformations because it had such a giant data set to analyze.

“Previous studies used much smaller cohorts assembled through treatment facilities or small claims databases, so they often ended up reporting only single-digit numbers of malformations, which is not enough to assess risk,” Suarez said. “Medicaid covers something like 40 percent of the nation’s deliveries — and we used nearly 20 years of data. So, our cohort is much bigger than anything that’s been analyzed in any previous paper, and that has let us drill down into specific malformations and provide detail that no one has provided before.”