James Dale: Alumnus Put a Spotlight on Discrimination Against Gays

A legal challenge to the Boy Scouts of America’s ban on gay scouts catalyzed the acceptance of gay youths as members

'The [U.S. Supreme Court] decision basically forced people to struggle with the issue, to decide which side they stood on and if they could align with an organization that discriminates.'– James DaleRutgers '93

When the Boy Scouts of America voted in 2015 to lift its ban on openly gay troop leaders and employees, James Dale wished he could celebrate the monumental shift. The decision had a loophole: local troops and councils, the executive board ruled, could continue to decide for themselves whether to allow gay volunteer leaders.

Nearly a quarter-century after the Rutgers alumnus sued the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) while a Rutgers student—in a case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2000—Dale viewed anything less than a complete repudiation of discrimination as unjust.

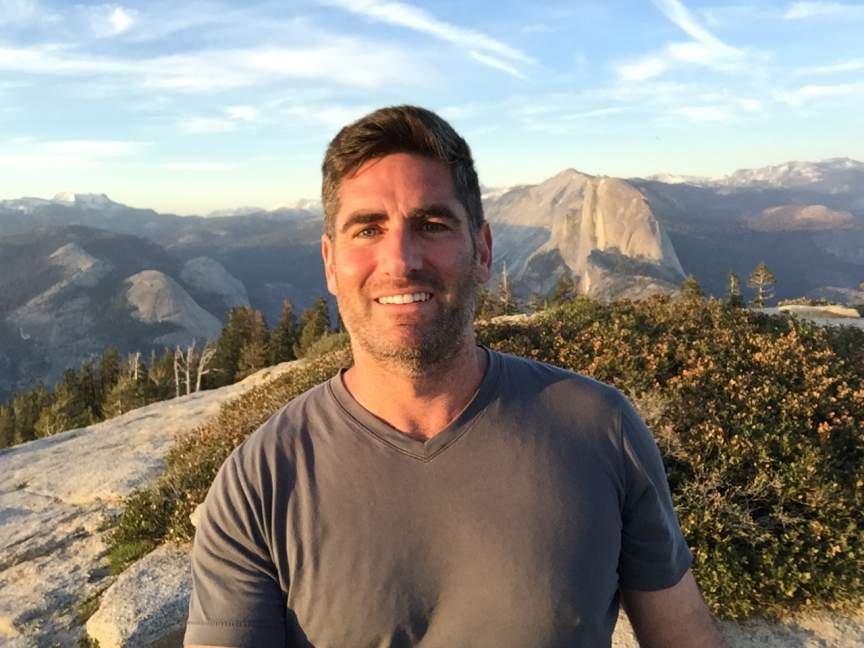

“It’s progress, yes. But after 25 years you would hope that they would get it right,” says Dale, 45, a 1993 Rutgers graduate who was dismissed from the Boy Scouts in 1990. “They’re still teaching young people that discrimination is okay. With discrimination there can be no half measures. Equality can’t be doled out in fits and starts.”

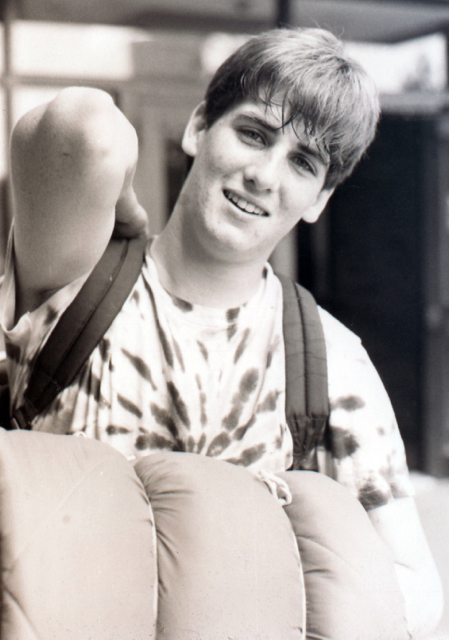

Dale joined the Boy Scouts when he was 8. He earned his Eagle Scout rank at 17 and was an assistant scoutmaster in Troop 73 in Matawan, New Jersey, while in college at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. The summer before his junior year, he received a vague letter from his local council leader saying he no longer met the standards of leadership. A month before, the Star-Ledger quoted the 19-year-old Dale in an article about a Rutgers seminar on the psychological and health needs of lesbian and gay teenagers.

From Eagle Scout to 'Diligent and Committed Plaintiff'

Dale connected with attorney Evan Wolfson, then with the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, to pursue a lawsuit. When New Jersey passed a law banning discrimination based on sexual orientation for places of public accommodation, their case gained strength. In July 1992, Dale sued the Boy Scouts of America in New Jersey Superior Court.

“It was a massive injustice,” Wolfson recalls. “Here was this young man who had spent more than half his life in the Scouts and had excelled in every way. He believed in the values of scouting, appreciated the training, and was a good example of it. And he was being kicked out not for doing anything wrong but for being gay.”

Wolfson quickly saw in Dale a powerful plaintiff who would help shine a needed light on gay youth as well as the organization’s discrimination. “He was a terrific role model,” Wolfson says. “Everything that made him an Eagle Scout made him a very committed and diligent plaintiff.”

A New Jersey Superior Court judge ruled in favor of the Boy Scouts in 1995, but a state appellate court reversed that ruling in 1998. The Boy Scouts of America appealed to the New Jersey Supreme Court, and the justices unanimously agreed in 1999 that the BSA violated state antidiscrimination laws. “The human price of this bigotry has been enormous,” wrote Chief Justice Deborah T. Poritz.

When the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the Boy Scouts’ appeal, Wolfson and Dale headed to Washington D.C. The 10-year battle ended in June 2000, when the high court, voting 5–4, ruled the organization had a constitutional right to ban gay members. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist said the First Amendment’s protection for freedom of association meant that the state could not force the 6.2-million member organization to adopt an unwanted message—in this case, acceptance of homosexual members.

Transforming Public Opinion

The decision was a terrible disappointment for Dale, who was working in public relations for New York-based nonprofits and putting off his dream of moving to California to stay close to the case. He remembers feeling lost and depressed at first. Soon, his focus sharpened on the bigger picture.

“The Supreme Court did the larger issue a favor,” he says. “The decision basically forced people to struggle with the issue, to decide which side they stood on and if they could align with an organization that discriminates.”

Many could not, and public opinion swiftly moved in Dale’s favor. In 2001, Oscar-winning director Steven Spielberg left his post on the Boy Scouts of America’s national honorary advisory board to protest the group’s anti-gay policies. Corporations stopped donating. In 2012, President Barack Obama and Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney announced they opposed the ban.

“The case played a huge part in transforming non-gay people’s understanding of who gay people are,” Wolfson says. “Once you accept that gay people are part of the family, that there is such a thing as gay youth, you can’t treat gay people as alien others who are easy to hate and fear.”

By 2013, when the BSA voted to admit openly gay Scouts but still ban gay adults as leaders, membership was at 2.6 million nationwide, a significant drop from the 6.2 million at the start of Dale’s case.

That same year, Dale made the move to the West Coast, where he worked as an advertising vice president and account director after a decade of having worked in advertising in New York. In 2016, he returned to New York to live with his partner and to continue speaking about the case and consider writing a book about his experience.

When Dale attended the gay pride parade in New York in June 2016, he took note of so many stores and businesses along the route hanging rainbow flags and messages of LGBTQ support.

“I remember a time when that wasn’t the case,” Dale says. “This is a much better place to be.”

Read about more Rutgers Revolutionaries

For media inquiries, please contact Dory Devlin at dory.devlin@rutgers.edu or 973-972-7276.