Rutgers University is at the forefront of research that addresses both questions by examining the genes and personal background of drug abusers.

The university recently secured a renewal of a multimillion dollar contract with the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) that could break new ground on the perennial “nature versus nurture” debate. The government-funded research will examine how the two forces work in tandem to create the conditions for addictive behavior.

“What we’re learning is that there are susceptibilities to addiction that we inherit but that require an environmental trigger,” said Jay Tischfield, who, as director of Rutgers’ Human Genetics Institute of New Jersey, played a lead role in securing the competitive contract. “What’s really new is the idea that the environment can, if you are from a genetically susceptible background, affect you to the extent that it changes your genetic make-up.”

The contract, the third the university has received for such work, will provide $8.8 million through 2012, and, if renewed, up to an additional $15.3 million through 2014. The money will allow the Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository to provide technologically advanced services that include extracting DNA from cell lines and preparing tens of thousands of samples for about 20 investigators nationwide.

“We wanted to make sure we had a solid resource in place for the scientific community to obtain high-quality DNA samples – and Rutgers provides that service,” said Joni Rutter, associate director for population and applied genetics at NIDA’s Division of Basic Neuroscience and Behavioral Research.

Indeed, the repository located on the Busch Campus is the world’s leading organization providing DNA, RNA, and cell lines to hundreds of research laboratories worldwide. The ability of the repository and similar facilities to examine large numbers of DNA samples has accelerated the pace of addiction research, Tischfield said.

“In the last five years this research has really taken off, because it now becomes possible to look at very large populations of people who are drug abusers or who are drug addicted,” Tischfield said. “For these studies, we are going to be collecting a lot of new subjects with a lot of conditions that were not previously studied in depth. We have a number of cocaine studies; we have methamphetamine studies; we have heroin studies.”

The repository receives blood samples from collection points across the nation. The samples are given voluntarily by drug users and are typically obtained during treatment.

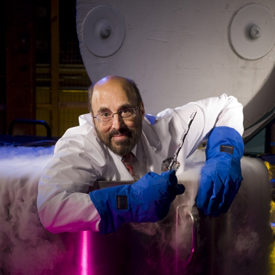

The repository’s staff grows cell lines from the samples and extracts DNA. The cell lines are stored at sub-zero temperatures in cryogenic tanks for further research, and the DNA samples are sent to researchers.

“That’s what the researchers are going to look for,” said David Toke, an associate director of the repository. “They’re going to look for those genes that are being expressed or not expressed in all those individuals with addiction and see if they can find some sort of commonality.”

Scientists generally agree that addiction is at least in part hereditary. But there is no consensus about which genes are involved, or how multiple genes work together to create the conditions for addictive behavior.

The NIDA study will look at not only genes but how environmental factors interact with the developing brain. Researchers will study personal information about the drug users, such as their socio-economic status, their education, whether their parents abused drugs, and many other factors.

“We are going to be processing the blood in different ways to look at changes in DNA that might result from the environment,” Tischfield said. “We will be documenting the environmental features such as whether they were raised in a two-parent home; whether they grew up in an urban, suburban, or rural setting; even religiosity.”

The chief benefit of the genetic research is that it helps scientists understand how addiction progresses and could help them find new medications or treatments.

“We get clues as to how the fundamental pathways get hijacked by the drugs and override our ability to make good decisions,” Rutter said.

But the research could also pinpoint the environmental triggers that lead to addiction.

“The good news here is, although we can’t change what we inherit, we can change our environment,” Tischfield said. “Once we understand how the environment interacts with the genetic information we inherit, we’ll be in a better position.”