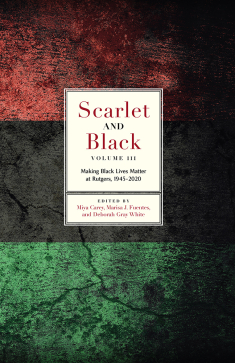

Final Scarlet and Black Book Shows How Student Activism Has Transformed Rutgers

Scarlet and Black: Making Black Lives Matter at Rutgers, 1945-2020 highlights the power of students’ commitment to justice and equity

In 1963 when Donald Harris, who had just graduated from Rutgers University, was arrested in Georgia and charged with insurrection for trying to register African American voters, students thought they could create a movement that would bring national attention to the atrocity that left the former football and lacrosse player and member of the Air Force ROTC facing the death penalty under Georgia law.

But, according to the forthcoming release and final book in Rutgers University’s Scarlet and Black series that recounts the university’s challenge to diversify, students found themselves struggling against a campus culture that, when not overtly racist, was apathetic toward Black rights.

The book, third in a series, recounts the role Black and Puerto Rican students played in challenging the university to diversify its student and faculty recruitment, invest in financial aid and initiatives that would help underserved students, expand its curriculum to include Black and Latinx scholarship and recognize the struggles toward freedom that were taking place across the world.

“The latest Scarlet and Black volume reveals through painstaking scholarship that transformational change at Rutgers did not occur quickly, easily or without the persistent commitment of students and others in the Rutgers community who confronted injustice and inequity,” President Jonathan Holloway said. “It is imperative that we explore our history as we continue the work toward inclusion and providing opportunity for all at Rutgers with steadfast intention.”

While Harris was released from jail when a federal judge declared the law under which he was charged unconstitutional after he spent 84 days locked up, his arrest inspired Rutgers students to continue to demand that the university make a commitment to justice and equity.

The final volume continues to uncover the legacy of slavery and Jim Crow segregation in New Jersey, what many consider to be a liberal state, said Deborah Gray White, Scarlet and Black coauthor and Board of Governors Distinguished Professor of History.

“Most important, however, it demonstrates how students, faculty and administrators can work together to implement change,” she said. “If the past is prologue, as I believe it is, the story revealed here presents important lessons for Rutgers as it strives to serve the state and nation in the 21st century.”

This volume presented tremendous challenges, White added.

“The horizontal expansion of Rutgers-New Brunswick into Piscataway and the university’s vertical expansion to Camden and Newark presented a complex story even before it was layered with the impact of the mid-century Black revolution on Rutgers’ campuses,” she said.

Scarlet and Black: Making Black Lives Matter at Rutgers, 1945-2020, covers a broad sweep of history, including what historians have called the “Black revolution on campus” – protests at Rutgers and other universities during the 1960s and 1970s that pushed American higher education to better reflect the nation’s diversity.

The final volume builds on volume one, which showed how Rutgers’ founders grew rich from the profits of slavery and justified Black debasement, and volume two, which followed Rutgers’s first Black students as they navigated white campus population and culture.

“Built on outstanding research conducted by Rutgers faculty, doctoral candidates, postdoctoral fellows and undergraduate students, the Scarlet and Black series provides an unflinching look at the ways Rutgers and many of its founders and leaders contributed to and profited from the disenfranchisement of people of color throughout its history,” said Christopher J. Molloy, Rutgers-New Brunswick chancellor.

“This third and final volume shows how student activists and others, through the latter half of the 20th century and beyond, succeeded in challenging Rutgers to become the exemplar of diversity, equity and inclusion that President Obama celebrated during his 2016 commencement speech and that we continue to improve upon today,” he said.

Some pivotal moments in the volume include:

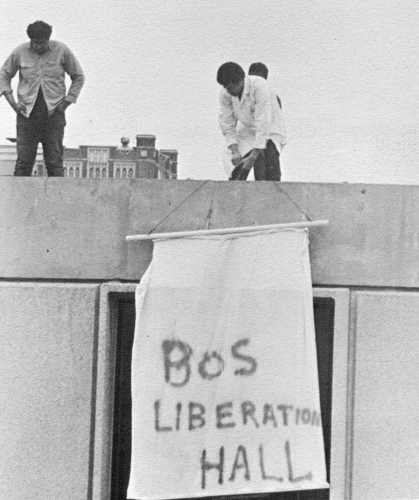

The Conklin Hall Takeover, February 1969

Members of the Black Organization of Students, frustrated by years of unfulfilled promises from university leadership, occupied a Rutgers-Newark administrative building with demands for equity in student recruitment and retention, faculty hiring, Black studies and other issues during a three-day protest. Rutgers’ then-president, Mason Gross, negotiated with the students instead of bringing in the police, which drew criticism from faculty members, politicians, the Rutgers Board of Governors and the public. The Conklin Hall demonstration was a fundamental event not only in the history of Rutgers but in the modern Black freedom movement as well.

Rutgers-Camden Students Protest, February 1969

Students barricaded themselves inside the campus’s College Center demanding that Rutgers support efforts to improve the urban community it inhabited. Though the city’s population was 40 percent Black, Rutgers-Camden’s student population, most of whom lived in the surrounding suburbs, was 98 percent white. The 20 Black students enrolled were mostly from Camden and deeply involved in advocating for city residents. A meeting with the university president and a vote by the faculty supporting students led to what the book calls the beginning of an era of persistent student activism that reshaped Rutgers-Camden.

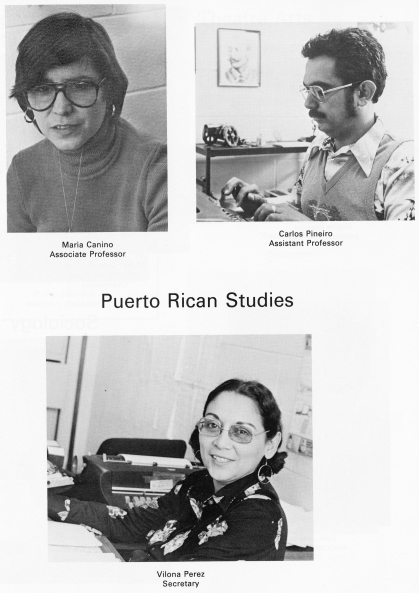

Rutgers’ Latino and Caribbean Studies Department at Livingston College, 1969

The creation of what is now Rutgers Latino and Caribbean Studies Department on the Livingston campus began as an experiment in recruiting Black, Latinx and other underrepresented students with an academic focus on social justice issues. But the university dedicated only meager resources toward a Puerto Rican studies program, which still thrived due to its dedicated faculty and demands of students. The department established New Jersey’s first Puerto Rican student theater group, held conferences on colonialism, established high school outreach resources and helped shape educational programs across the United States.

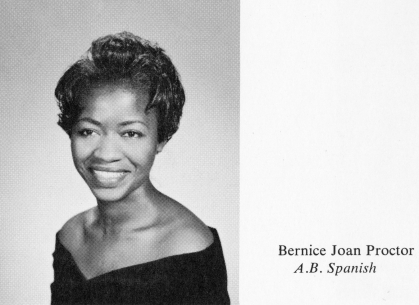

Black and Latinx Feminist Consciousness at the All-Women’s Douglass College and the Coed Livingston College

Student Bernice Proctor Venable organized petitions against the arrest in 1960 of 100 anti-segregation protesters in Tennessee and with the NAACP in New Brunswick fought housing discrimination against Black students. The Douglass Black Students’ Committee organized a cafeteria protest in coordination with the Conklin Hall takeover, advocated for African American studies courses and successfully demanded space for African American cultural events. Black Douglass women students also demonstrated in front of a segregated white fraternity house where Black Rutgers College men were being threatened with baseball bats by white men.

Don Imus Comment About the 2007 Women's Basketball Team Leads to Uproar

The 2007 event in which Scarlet Knights women’s basketball head coach C. Vivian Stringer and her team’s student-athletes turned the national uproar over radio host Don Imus’s sexist and racist comments into a demand for recognition of the dignity of Black women and all women. After several days of national outrage and intense emotion, Rutgers Athletics held a news conference in which Stringer and the team used the experience to open up a dialogue about sexism and racism. In the end, the message of female empowerment took hold and raised the consciousness around larger issues of race and gender.

Since 2015, when the committee’s Scarlet and Black Project was launched as part of the commemoration of the university’s 250th anniversary in 2016, scholars have explored the experiences of two disenfranchised populations at Rutgers: African Americans and Native Americans.

The release of the last volume arrives during a time when the Black Lives Matter movement is creating a space where people seem to have more of a desire to learn about African American history, White said.

"Volume three of the Scarlet and Black book series illuminates the long history of racial justice activism initiated and sustained by Black and brown students across Rutgers campuses, across New Jersey and the nation,” said Marisa Fuentes, Presidential Term Chair in African American History and an associate professor of history and gender studies. “As the concluding volume in the series, its focus on institutional racism and the efforts of Black and Puerto Rican students to end police violence, community displacement and make spaces for scholarly attention to histories of racial oppression and resistance brings Rutgers history to the present in powerful ways.