(This story was updated August 26, 2011)

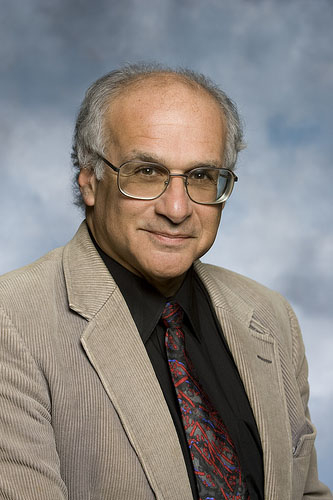

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001 left New York City with an environmental disaster of epic proportions. Many first responders, construction workers and nearby residents who breathed air full of aerosolized cement, glass, minerals, metals and combustion soot contracted respiratory diseases that have become chronic health burdens. Paul Lioy, director of exposure science at the Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences Institute, began studying the disaster and government response shortly after the attacks. In 2010, he published a book, Dust: The Inside Story of its Role in the September 11th Aftermath. The book came out in paperback in 2011, with an epilogue that discusses how we are better prepared to respond to catastrophes.

Rutgers Today: What lessons have you learned about environmental exposure during accidents and disasters?

Rutgers Today: Are we better prepared now for environmental disasters?

Lioy: We saw improvements in the way we dealt with the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. There were better protocols and process to protect those who worked on the cleanup. But we still have some gaps. We need people trained and ready to go. People have been trained, but online updates are not as good as frequent and detailed drills. I also see the need for better personal responsibility and resiliency among all citizens. We don’t spend enough time looking at that issue. Personal preparation and resilience is very important for survival in the face of chaos.

Rutgers Today: What were health officials most concerned about in those first days after the terrorist attacks?

Rutgers Today: Where do things stand, ten years later?

Lioy: Most of the lawsuits have been settled, and the 9/11 First Responders bill has been passed. So there is movement toward closure. We understand the respiratory effects of the disaster, but cancer is still a big unknown. At this point, there are no truly quantifiable higher incidences of cancer attributed to 9/11. Still, we must remember that in the general population, about one in four Americans contracts a form of that disease. So the data will have to be examined carefully going forward.