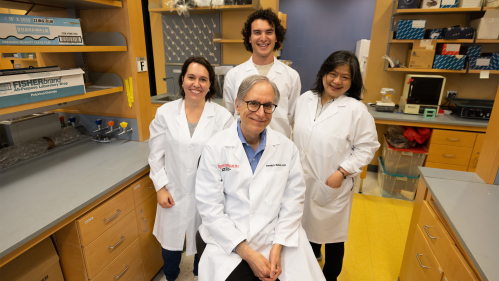

For Director of Child Health Institute, Training Tomorrow’s Scientists is a Family Tradition

From the earliest days of his childhood, Arnold B. Rabson’s fate as a physician-scientist was sealed.

His parents were pre-eminent pathologists whose studies in virology changed the course of medicine. Alan S. Rabson advanced cancer research while Ruth L. Kirschstein developed a safety test for the polio vaccine and was a vigorous supporter of early work that led to the development of HIV treatments. Both held top roles within the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Their love for their work motivated Rabson to follow their footsteps into a scientific career, but he quickly found his own passion for the family business. In addition to illuminating the mechanisms of HIV and cancer, he has bolstered scientific inquiry at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, where he directs the Child Health Institute of New Jersey and is the Laura Gallagher Chair of Developmental Biology and a professor of pharmacology, pediatrics, and pathology and laboratory medicine.

Now, as Father’s Day approaches and Rabson looks back on his late parents’ contributions, he’s proud to be continuing their legacy, from making discoveries in the lab to nurturing young scientists — though he never expects to match his father’s record of referring more than 14,000 people to cancer specialists, from taxi drivers to celebrities like Katie Couric.

“My parents were all about service,” Rabson said, “and doing the best they could for people who needed help.”

Growing Into Science

Rabson realizes his childhood was extraordinary.

Raised on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland, he attended teas with Nobel Prize winners and shadowed his father during weekend lab checks and medical conferences.

“We were reading Watson's Molecular Biology of the Gene together when I was in high school, rather than biographies of sports figures,” Rabson said, “because these were our heroes.”

After graduating in 1973 from the Sidwell Friends School in Washington, D.C., Rabson joined a program that encompassed both college and medical school at Brown University, where he was mentored by Albert E. Dahlberg, a professor of medicine, renowned biochemist and family friend. After a residency year at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Rabson headed to the NIH.

There, he studied cancer-causing retroviruses until the day Malcolm A. Martin, chief of the Laboratory of Molecular Microbiology, obtained a vial of HIV from France. After that, Rabson and his colleagues worked nonstop to produce a DNA copy of the HIV genome capable of infecting human cells.

Created in 1985, their model made it possible to deconstruct the devastating virus, enabling pharmaceutical companies to develop treatments.

It also allowed Rabson and his collaborators to learn how HIV worked — by hijacking the activity of the immune system, specifically through the NF-kappaB transcription factors. Later, at Rutgers, Rabson determined that mutations of the same proteins drive both leukemias and lymphomas.

A Leader at Rutgers

It was 1990 when Rabson joined Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School to conduct research at the Center for Advanced Biotechnology and Medicine. Later, he held leadership roles at the Cancer Institute of New Jersey before being tapped in 2007 to lead the Child Health Institute — conceived by Johnson & Johnson and supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Since then, Rabson has recruited about 80 researchers to the institute, who work under the direction of 13 faculty investigators researching four areas: inflammation, immune, and infectious diseases of childhood; neurodevelopment and autism; pediatric cancers and stem cells; and childhood obesity and metabolism.

Their achievements have included finding new ways to regenerate damaged peripheral nerves; characterizing previously unidentified immune cells, such as some that drive asthma and inflammatory bowel disease; and discovering genetic causes of some autism subtypes and congenital muscular dystrophy.

“We're in the early stages,” Rabson said, “but the caliber of these discoveries has real potential clinical implications.”

Amy P. Murtha, dean of Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, praised Rabson’s contributions.

“His mentorship, recruitment and support of world-class researchers continues to foster cutting-edge science that is moving the field forward and helping improve child health and quality of life,” she said.

What gives Rabson the greatest satisfaction is mentoring the institute’s investigators and watching them teach their post-doctoral students.

“I do less science myself now,” he said, “but the real fun part is carrying on something my parents felt was very important — training the next generation of scientists.”