Beating Princeton to Settle a Score

Amid his many successes, Paul Robeson found particular joy in defeating his former hometown university

On Paul Robeson’s last day at Rutgers, one of his dreams came true. And it didn’t take place on the football field or in a classroom. It happened on the baseball diamond. Rutgers beat Princeton, a feat that had eluded Robeson since his first year.

But beating Princeton wasn’t all he achieved at Rutgers from 1915 to 1919. By that time, Robeson had received 12 varsity letters in four sports and dabbled in a singing career that would blossom just a few years later. Such accomplishments are evidence that, while at Rutgers, Robeson displayed seemingly limitless talent even as his career path and affinity for justice were already taking shape.

Robeson was a solid catcher on the baseball team.

As a Rutgers athlete, Robeson’s top sport was undoubtedly football, for which he’d become legendary. On the baseball team, he was a solid catcher, but not much of a hitter, with a batting average of less than .200. And in track and field, he was considered a decent shot-put, javelin and discus thrower.

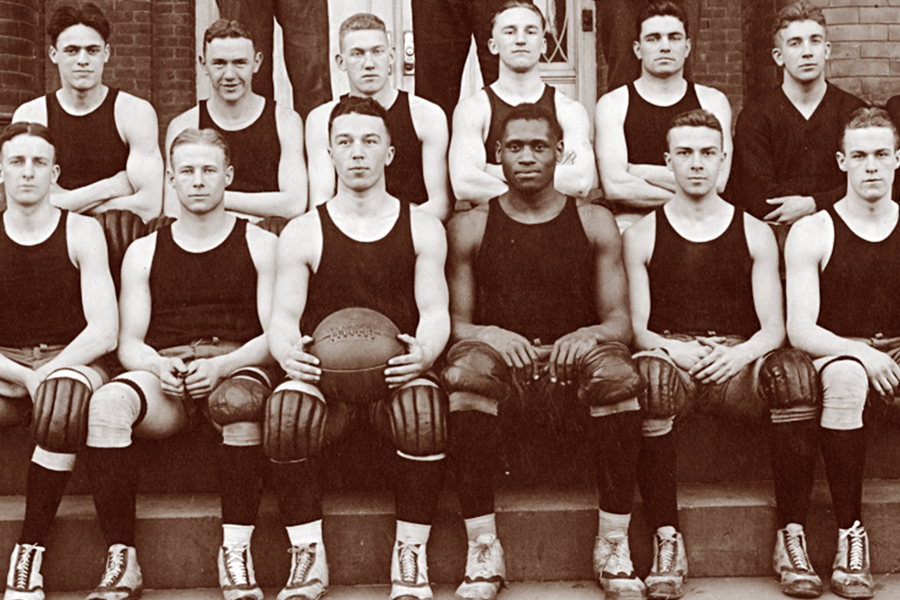

But playing basketball, at center or forward, he was also regaled as exceptional. To earn extra money, on weekends and holidays, he even played for a semi-pro team, the St. Christopher Club in Harlem, considered one of the best in the country at the time. Singing, however, brought more income for him, landing gigs at private parties and church events. It only made sense; with his deep bass-baritone, Robeson sang every chance he got, even if money wasn’t involved, as friends would later attest.

Music was a huge influence, going all the way back to Robeson’s childhood in Princeton, where he lived in the segregated, African-American section of town. “Here in this little hemmed-in world where home must be theater and concert hall and social center, there was a warmth of song,” he wrote in his 1958 memoir, Here I Stand. “Songs of love and longing, songs of trials and triumphs, deep-flowing rivers and rollicking brooks, hymn-song and ragtime ballad, gospels and blues, and the healing comfort to be found in the illimitable sorrow of the spirituals.”

But Princeton was also where he’d lost his mother to a house fire, and where his father, the pastor of a white-controlled, all-black church, lost his job after bringing attention to addressing violence against African Americans in the South. It was also home to Princeton University, which refused entry to students of color, including one of his older brothers, William.

So by the time he arrived at Rutgers, Robeson was anxious to be on any team that could beat Princeton. His first three years, however, he didn’t get the chance. The schools’ football teams only played each other once, during Robeson’s first year, with Princeton spoiling what otherwise would have been an undefeated season for Rutgers. And in baseball and basketball, Princeton won game after game.

Robeson also excelled on the basketball court at Rutgers.

Meanwhile, Robeson enjoyed a healthy social life off campus, particularly when he visited the nearby cities of Trenton, Philadelphia, Newark, and New York. Women especially liked him, but he favored one in particular—Geraldine Neale, who was training at New Jersey State Normal School at Trenton (now the College of New Jersey) to become a kindergarten teacher. They’d meet as often as possible, and he’d tell her she was the only one for him. But Neale, sensing Robeson couldn’t be tied down, refused his marriage proposal. As with his singing career, matrimony would have to wait until he’d settled in his next place of residence, Harlem.

Paul continued to focus on more immediate goals. In one basketball game, against Princeton, he performed particularly well, dominating and outscoring his counterpart at center. With just 10 minutes left in the game, and Rutgers up by nine points, it appeared as if his dream of beating Princeton would be realized. But in overtime, Princeton won by two points.

Then June 10, 1919, the day of Robeson’s graduation, arrived. He capped his academic career by delivering an address at his class’s commencement. But his mind was also on one more game—this one baseball, to be played at home that afternoon.

Rutgers, as usual, was considered the underdog. But Robeson, who scored one of five runs that day, played with abandon, as did the rest of the team, especially the pitcher, George “Red” Rule, who gave up just four hits and scored a run himself.

The final score: Rutgers 5, Princeton 1. Robeson’s dream had come true.

Rutgers is honoring Paul Robeson’s legacy as a scholar, athlete, actor, singer and global activist in a yearlong celebration to mark the 100th anniversary of his graduation. Check back with Rutgers Today throughout the year as we present a special series chronicling Robeson’s life and his influence on generations. Read previous articles in the series for an overview of his life, an exploration of his father's influence and his childhood in Somerville, his time on the football field at Rutgers and all around excellence as an undergraduate student.

Learn more about the celebration by visiting robeson100.rutgers.edu or by following #Robeson100 on social media.