Recalling a Restive Rutgers

Members of the Classes of 1969, 1970, and 1971 recall their experiences at Rutgers living through extraordinary events: the Vietnam War, cultural and civic turmoil, and calls for Black student rights.

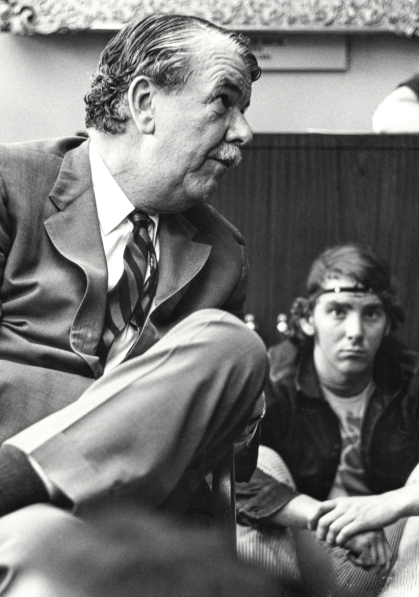

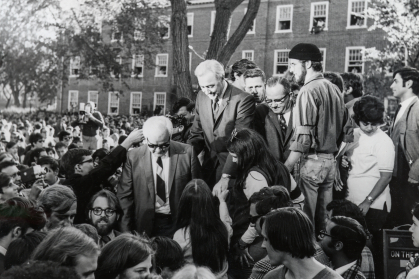

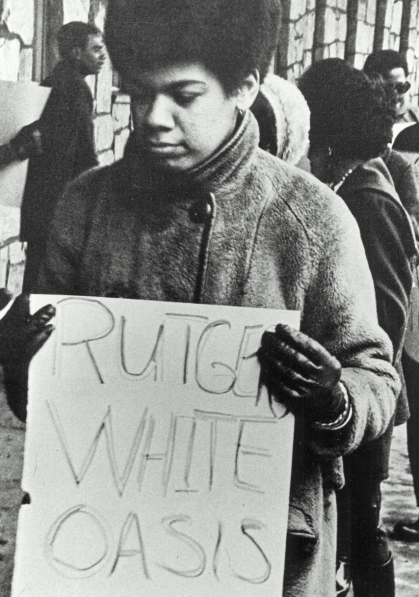

A half a century ago, during the late 1960s, the nation was engulfed in unprecedented political, social, and cultural change. College campuses were places of growing social awareness and political action, often flashpoints of debate and unrest. Black students at Rutgers University–New Brunswick, Rutgers University–Newark, and Rutgers University–Camden protested the paltry number of African American students and faculty on campus as well as the lack of academic and cultural support by the administration. The United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War drew considerable criticism, but also some support, from students and faculty members. Students and faculty found a sympathetic ear in Mason Gross, who served as Rutgers president from 1959 through 1971. Time and again, in words and deed, he supported students and faculty members in their right to protest and make demands of the university. Many alumni attending the university remember a restive Rutgers as if it were yesterday. Rutgers Magazine asked members of the Classes of 1969, 1970, and 1971 (which is celebrating its 50th anniversary in the fall) to recall the times and how they were affected in ways small or significant by events playing out on and off campus.

A Turn to the Left

I entered Rutgers–New Brunswick in fall 1965 as a biology major, ROTC participant, and Republican—one of Barry’s Boys. I was also vice president of the right-wing group Young Americans for Freedom (YAF). As the Vietnam War intensified, YAF conducted a dirty trick that started to turn me to the left. A popular student was running for class president, and the Republican students distributed campaign literature the evening before student voting, essentially accusing the liberal candidate of supporting North Vietnam in the war. The maligned candidate was caught going out after midnight to refute the claims and, because election rules did not allow campaigning the day of the election, he was disqualified.

—Kevin J. Hackett AG'69, GSNB'71

Weapon of Mass Destruction

One of the weapons deployed in the Vietnam War was napalm. Dow Chemical, which produced and supplied the U.S. military with it, was also a major recruiter on college campuses. In fall 1967, Steve Kessel RC’68, Peter Kuznick RC’70, and I were invited to debate a Dow spokesperson on the use of napalm. The debate, in a packed Scott Hall, provided a platform to speak about the senselessness and immorality of the war and about my many relatives exterminated by Zyklon B in Nazi death camps. I did not call the Dow spokesperson a war criminal, but I let the analogy sink in. Based on the audience response, we won the debate and may have helped reduce the lines at Dow’s recruitment desk.

—Robert Leonard Berkowitz RC’69

Protest Art

Rutgers–Camden was a small commuter campus during the late 1960s. There was no university housing. No robust student life outside of classes, the student center, and Greek organizations. Many students worked. At a time when there was a visible sense of growth on campus, an air of anger and discontent erupted at Rutgers–Camden. An 8-foot-high dark wall was built around the new Armitage Hall. During the early hours of a 1968 school night, Greek students created protest murals on the entire length of the wall. It became the ultimate message board, right there in the middle of campus. It conveyed student dissatisfaction with our country and its politics.

—Charles M. Ivory CCAS’69

The Conscience of a Generation

In 1966, I chose Rutgers–New Brunswick over Cornell after reading a Newsweek article calling Rutgers “the Berkeley of the East.” I joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). But in my first semester, finding SDS’s message too radical for most students, I founded the Rutgers–Douglass Committee of Conscience to spark the antiwar movement. In 1968, I joined professors Warren Susman and Lloyd Gardner in denouncing both the Democratic and Republican warmongers during an election eve teach-in at Records Hall. I also represented the student body at the huge convocation in the College Avenue Gym following the cancellation of classes to protest the April 1970 invasion of Cambodia. The other speaker was President Mason Gross. What exciting times those were!

—Peter Kuznick RC’70, GSNB’75,’84

A Sacred Right

Democratic vice-presidential candidate Edmund Muskie planned to speak at Rutgers–New Brunswick in October 1968. The announcement prompted planned protests by numerous liberal and radical groups over his support for the Vietnam War. As editor in chief of The Daily Targum, I wrote a column arguing against his right to express his views because he supported an unjust war that killed thousands of innocent civilians. Fearing mass disruptions, Muskie canceled his visit. A year later, I embarked on a 50-year career as a journalist and deeply regret to this day writing that column. I have come to appreciate that our First Amendment right to peaceful free speech should be cherished and protected, even if we revile the content. I wish I had written that in 1968.

—Owen Ullmann RC’69

A Disservice to Those Who Served

In spring 1968, my fiancé (Doug Martin AG’67) was leaving for a survival school in California. He had received both his dreaded draft notice and acceptance to Navy Officer Candidate School on the same day. Thinking the Navy was the safer bet, he enrolled. Far from safe, he was assigned to patrol Vietnam’s Mekong Delta in a Swift Boat. He wore his uniform the day he visited me at Douglass College at Rutgers–New Brunswick. As we walked along George Street, Rutgers students drove by shouting obscenities and spitting at him. I was shocked. The war was unpopular, but he had answered the call of his country. It is still hard remembering the way he and others who served were treated.

—Terre Williams Martin DC’69

The Day That Rutgers Closed

When Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968, sparking riots nationwide, members of the Rutgers Student Afro-American Society at Rutgers–New Brunswick gathered that day to decide a response. We chose to demand that Rutgers close the university. Bryant Mitchell RC’69 was chosen to meet with Rutgers president Mason Gross. I went with Bryant, who had been taking a philosophy class taught by Gross, to the president’s residence, arriving at 11 p.m. He invited us to join him in his living room. I watched in silence while Bryant and Gross discussed the King assassination for 45 minutes, with Bryant insisting that Rutgers be closed to honor the slain civil rights leader. It's my recollection that Gross said: "Rutgers didn't close for JFK's death." Bryant responded: "This is now and it's different." Rutgers was closed on April 9. [Editor's note: Gross had ordered the closing of Rutgers following JFK's assassination as well.]

—Michael Jackson RC’71

G.A. Approval

Fashions in the late 1960s were much more formal and gender normed. Young ladies did not wear T-shirts; I wore more than my share. My junior year at Douglass College at Rutgers–New Brunswick, I chaired Campus Chest, the collegiate arm of United Way, and we raised money for student projects. Before a student could post a sign on a campus bulletin board, however, it had to be stamped in red ink with “Approved by G.A.” (Government Association, the student review board). We sold white T-shirts with small red letters on the chest that read “Approved by G.A.” They may not have been popular with the administration, but they were a big hit with students: that year we raised a record amount, which was used to build a playground in New Brunswick.

—Linda Feinerman Seth DC’69

Running Solo

I was the lone Black runner on the varsity track team at Rutgers–New Brunswick in early 1968. In response to a boycott of a New York Athletic Club track meet by Black athletes, Rutgers’ track coach Les Wallack told The New York Times, “If there were a Negro athlete on my mile relay, I would require him to run if he was going to remain on the team.” I was not informed of this position and was directed to attend the meet. But I got food poisoning and missed it. I learned I had been kicked off the team. After protest letters to student newspapers, Coach Wallack and athletic director Al Twitchell RC’35 apologized and invited me back. I declined, ending my track career. I redirected my energies to working as a student leader and helping to organize the 1969 demonstrations to address the concerns of Black students.

—Jerome Harris RC’69, GSNB’72

Pro Football or Vietnam?

After my last season on the Scarlet Knights football team (I was MVP), I had one big thing to worry about in the spring of 1969: my student draft deferment would expire after I graduated as an art history major. I was invited to try out for the Hamilton Tiger Cats of the Canadian Football League; maybe my draft number wouldn’t be called. I was so worried that I don’t remember the graduation ceremony. Indeed, while in Canada, I was ordered to report for military duty. My father, an Episcopal minister, supported me regardless of my decision: stay in Canada or report. I left Canada, reported to duty, and was sent to Vietnam, serving as a combat military policeman and lead jeep gunner of supply convoys for the 25th Infantry Division.

—Bryant Mitchell RC’69

A College Education for All

In February 1969, members of the Black Student Unity Movement locked the doors of the student center at Rutgers–Camden to get the students’ attention, and they did! They placed large chains with padlocks on the doors to prevent entry. Students who usually purchased breakfast (or at least coffee) in the morning before class couldn’t do so. The protesters wanted graduates of any Camden high school to be able to attend Rutgers, no matter what their GPA or SAT scores were. The protest culminated in a meeting with the Rutgers administration on a course of action. The event was a good thing to understand and was a growth moment for me in many ways.

—Elaine Welsh CCAS’70

The End Justified the Means

I was part of a small group of Black students at Rutgers–Camden, where we felt unwelcome and grew incensed over the lack of Black and brown students, faculty, and administrators. In 1968, we formed the Black Students Unity Movement, which helped protect students from feeling isolated and marginalized. In February 1969, we presented the administration with a list of 24 demands. When negotiations broke down, a tipping point had been reached, and two weeks later several students staged a protest by occupying the student center, escorting white students out, chaining the front doors shut, and presenting student demands to a mediator. A media feeding frenzy ensued. The 35- to 40-minute drama was justified: it led to the diversification of Rutgers–Camden.

—Roy L. Jones CCAS’70

The Moon Landing That United Us

During the summer of 1969, I represented Rutgers as an intern with the United Nations International Labor Organization in Geneva, Switzerland. It was a big deal for me and a great opportunity. But the important story for everyone that summer was the moon landing. I went to a pub with students from around the world to watch it on television. Cheers erupted when Apollo 11 landed and when the first man, Neil Armstrong, an American, walked on the moon. I cheered for America and what we had accomplished. The international students were cheering just as loudly. Yes, they were cheering for the U.S.A., but they were also cheering for the achievement of all mankind. At that moment, we were all one.

—Cynthia Stark Kastner NCAS’70

Making Their Voices Heard

The late ’60s. The Newark riots of 1967. The takeover of Conklin Hall in February 1969. Rancorous debates raged across the Newark campus among students and faculty over these events. The original buildings for the College of Arts and Sciences quad were just being completed and classes were held throughout downtown Newark. In the middle of the turmoil, the campus awakened and demanded that the university’s Board of Trustees provide better recognition and funding for our space and our education. All the differing voices on campus came together to take our call for the needs of students down to Rutgers–New Brunswick for a rally of 600 students and 60 faculty on April 7, 1969. We learned that change sometimes occurs from quiet reflection and sometimes by determined action.

—Dominick Mazzagetti NCAS’69

Hitting the Right Notes

In May 1970, I was a junior at Rutgers–New Brunswick when the Kent State students were fired upon. Never very political or a social justice follower, I was appalled that this could happen and determined that I should do something. So I talked some of the other music majors into giving a concert. Just a week after the shootings, we, the Concerned Student Musicians, presented “A Concert of Serious Music” at the Douglass student center. We raised about $100—not bad for college students at that time—which went to the Chapel Conference of Douglass College, the group working on responses to the shootings. We had singers, pianists, clarinet (me), oboe, and cello all doing what we did best and what was dear to our hearts.

—Martha Boughner DC’71, GSE’86

Earth Day and the Draft

I was on an emotional high after the first Earth Day celebration at Rutgers−Camden in 1970. It did not last long. The United States then invaded Cambodia, setting off nationwide demonstrations and calls for a national student strike. An anti-Vietnam War strike resolution passed on May 5 at Rutgers−Camden, ending classes for the semester. I applied for conscientious objector status to perform civilian service in lieu of military service; my low draft lottery number solidified my fate. On May 31, we seniors celebrated the first on-campus graduation. After months of defense, denial, and then a successful appeal of my application, I began two years of civilian service in May 1971, thankful and proud of my contributions.

—Wayne R. Ferren Jr. CCAS’70

Strike!

President Richard Nixon announced the invasion of Cambodia in April 1970, but that was not the sole reason that Rutgers–New Brunswick students launched a strike in protest. The strike began where most major events at Rutgers got their start—at Princeton. When word spread that 3,000 Princeton students voted to strike on April 30, Rutgers students followed suit on May 4. And The Daily Targum, where I was an editor, took an unusually opinionated role in helping the strike get underway. The May 1 edition of the newspaper featured a banner exclaiming: “Strike Monday!” The Targum became the campus strike newspaper—not an example of unbiased journalism, but a stark sign of the times.

—Tony Mauro RC’71

Living the Examined Life

Every day in 1969, there was another headline: Cambodia bombed, a protest in Washington, D.C., a student strike somewhere. Life swirled around us at Rutgers–New Brunswick in 1969–1970, and then there was the calming voice of philosophy professor Renée Weber, the person whose example had persuaded me to major in philosophy and with whom I had an independent study course in spring 1970. “What does Hegel’s thesis-antithesis-synthesis mean to you now?” she would ask. Then, “Sartre said, ‘Freedom is what you do with what’s been done to you.’ Does that apply to you? Today?” I remember the headlines of that time, but I remember more vividly the questions Professor Weber asked because they were always about the fundamental Socratic question: Am I living an examined life?

—Robert McGarvey RC’70

Tin Soldiers and Nixon Coming

Following the horror of the student killings at Kent State in May 1970, Pete Spring CCAS’70, who was a friend and classmate, and I traveled by bus the following week from Rutgers–Camden to the March on Washington to join the 100,000 people protesting the killings and the Nixon administration’s invasion of Cambodia. Then I received a notice from the federal government to report for a draft physical two days before graduation. It certainly wasn’t the way I planned my graduation celebration, to say the least. What a Rutgers graduation present!

—Stephen Tabin CCAS’70

Calming Words

Amid the national unrest in 1970, the day of my graduation, June 3, was warm and sunny for the first commencement ever at Rutgers–Newark. Only a month before, on May 4, the Ohio National Guard had fired at Kent State University demonstrators, killing four students and wounding nine others, leading to college closings and canceled exams. With the unsettled mood in the country, the commencement committee at Rutgers sought calm. Participants wore white armbands for peace. U.S. Representative Shirley Chisholm gave the address. As the valedictorian, I spoke about the enduring value of being kind—of respecting others, being willing to listen to different opinions, and seeking a positive way forward. Fifty-one years later, that message remains relevant.

—Sharon P. Smith NCAS’70, GSNB’72,’74