Playing Through the Pandemic

Since entering the Big Ten Conference in 2014, the Scarlet Knights have faced some of the toughest competition in collegiate sports. The Rutgers teams, however, have never encountered a foe quite like their collective opponent during the 2020–21 sports seasons: COVID-19. Every step of the way, before they made any memorable moves on the field or court, players had to abide by stringent safety protocols. The demands circumscribed the way that student-athletes lived and studied, worked out and practiced, and traveled to and from sports venues, particularly away games when jets, airports, and hotels were necessary.

The protocols, such as frequent testing, were daily reminders of the lurking coronavirus, which could not only infect individual players, but also force teams to drop out of competition until they were cleared to resume play. Miraculously, Rutgers teams by and large went unscathed and completed their seasons. Beginning last June, when the first spike in COVID-19 infections was ebbing, football and basketball players arrived in Piscataway for their usual summer training. When the Big Ten reversed itself and made the decisions, in September and November, to go ahead with truncated football and basketball seasons, players and personnel became veritable canaries in the coronavirus coal mine: could they stay safe, play the games, and become models for the spring sports teams to emulate?

The job of safeguarding practice facilities and sports venues at Rutgers University–New Brunswick was the responsibility of Matthew Colagiovanni, the senior associate athletic director for facilities, events, and operations for Rutgers Athletics. He and his teams were in constant communication with university operations staff, sports medicine personnel, and their Big Ten counterparts to establish best practices and procedures.

“I look back on the last 12 months or so, and it’s been amazing from where we started with COVID-19 and where we are today,” says Colagiovanni, who admits to anxious moments before Rutgers was able to safely host the football team’s first home game at SHI Stadium on October 31. “It’s definitely been a challenge, but we have been successful keeping our teams going whereas some Big Ten schools have had some shutdowns. We have had a solid group of workers, including the medical staffs.”

The Hale Center, which is the training facility within the football stadium, was festooned with directional signage and arrows, mask-wearing directives, and ubiquitous hand-sanitation stands—common sights today but novel during the early months of the pandemic when the coronavirus was imperfectly understood and testing was unavailable. Players, always masked and socially distanced for any team function, now used several locker rooms, not just one. Sessions for weight training were staggered, with a fraction of the usual occupancy, and the equipment was regularly sanitized and the room air purified. When it became available, a daily testing program, established by the Big Ten, was implemented for players, coaches, and staff. For the unfortunate few who tested positive, there was a designated dorm for quarantined players. Players’ housing arrangements, whether on or off campus, were intended to limit the likelihood of infection during their downtime from competition.

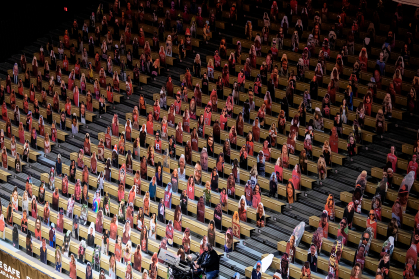

SHI Stadium and Rutgers Athletic Center, which is home court for the basketball teams, underwent many of the same steps as the Hale Center to prepare the venues for competition. Only personnel regularly tested were allowed in the facilities. Event staff and security were masked, as were coaches and players not competing. Access to the field or court was extremely limited. Every last person entering the facilities was on an approved list and accounted for.

“COVID was the team’s No. 1 opponent,” says football head coach Greg Schiano, who made a point to preface every team meeting with the need for players and staff to remain vigilant. “We were often forced to change our daily and weekly schedule due to false positives, halting certain individuals and groups. I am most proud of how our players, coaches, and staff sacrificed for one another to be able to play and coach the game they love.”

Players’ and coaches’ ardor was tested when teams hit the road for away games, usually an occasion to build camaraderie and bask in the limelight of participating in Big Ten athletics. Travel, especially for the bigger team sports, required the most demanding logistics and precautions to protect players, coaches, and support staff. There were prescribed steps for getting personnel from Rutgers to airports, from airports to hotels, and from hotels to sports venues, and back again.

In order to keep everyone properly socially distanced, two buses, with seating assignments, were required instead of one (operated by drivers who were tested the day before and the day of travel and then lodged with the team). Likewise, twice the number of hotel rooms had to be reserved because it was now one player to a room, not two. Would hotel ballrooms be big enough for a team meeting? Where would team meals be served and how? Each player on the women’s basketball team, for instance, had to eat meals, delivered by the hotel staff, alone in her room. During the NCAA Tournament, players could barely circulate beyond their own rooms, not to mention leave the hotel. When they first arrived, the team was quarantined until its members were able to produce two negative tests in two 12-hour periods.

Safety protocols were largely dictated by the guidelines of the Big Ten, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and local ordinances, which were in flux and weren’t always in accord with one another. A daily fact of life for everybody was testing, sometimes twice a day. And the staples of safety—mask-wearing, social-distancing, and hand-washing—were always in effect, right up to the moment that players entered competition—and left it.

“All year long, we had to navigate COVID-19 and all types of obstacles that came with it,” says Steve Pikiell, the head coach of the men’s basketball team. “Our guys came together in June, and we went through the whole season and never had a COVID pause. The team made a lot of sacrifices to fight through COVID and help us have a successful season.”

Despite the challenges of the pandemic, all Scarlet Knights student-athletes were winners: they got a season of play in—safely.

“The guys handled it really well this season,” says Peter Barron, the director of baseball operations. “I have to give them credit. It’s college. It’s supposed to be fun—the best years of their life. Yet, they are being asked to do all these things, from testing to taking classes online. They certainly were aware that the 2020 season was taken away from them. So, everyone’s mentality was, ‘This is a lot better than not playing at all.’ ”