Learning From Afar

When Rutgers sent faculty and students home for their safety during the COVID-19 crisis, the academic year continued through remote instruction, a new learning experience that proved to be effective. Its successful adaptation bodes well for the university if remote learning is necessary in the future.

As the COVID-19 pandemic gathered force in early March, Rutgers took the precautionary step of canceling on-campus classes and sending faculty and students home to resume instruction through remote learning. In just two weeks, from March 10 to March 23, faculty, with the assistance of the Office of Information Technology and other IT units across Rutgers, successfully moved 12,600 sections of Rutgers courses to online instruction. Meanwhile, close to 70,000 students adapted to the new format as well. The swiftness of the switch was startling: Webex, a web conferencing software, was used for 278 daily video meetings before February 12; just two months later, that number skyrocketed to 5,213. In managing to complete coursework for the spring semester, faculty and staff shared common challenges, such as corralling the right technology and establishing routines that would help students continue to learn under extraordinary circumstances. With course content and methods of instruction varying widely, instructors faced how best to get information to students and assess their learning. Most professors conducted their classes from their own homes; some of them returned to campus and led classes, safely, from empty instructional spaces featuring the latest technology allowing the rooms to function as studios in which they could video conference, stream, or record for class.

A particularly thorny question was how to compensate for courses with significant hands-on components. What do you do when your classroom is a geological site in the New Jersey Highlands, a sculpture studio, or chemistry laboratory? For Rutgers University–Newark geologist Alexander Gates, trips to geological formations in New Jersey are key to teaching “Structural Geology.” On fieldwork days, students normally spend hours outside taking measurements to collect data. With that option off the table, how could he teach his students about measuring, for instance, structural characteristics of a Ramapo Fault outcropping between the Piedmont and Highlands provinces in North Jersey?

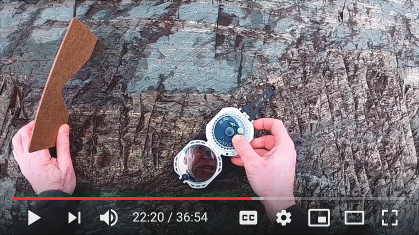

Having never taught remotely—“I thought I was too old to do this,” Gates says—he used online tutorials and consulted with the department’s IT staff to master the basics. Gates also hit on the solution of purchasing a GoPro camera, popping it on his head, and going into the field alone to create virtual field trips from a student’s point of view. “They just see my hands collecting data as if they were their hands,” Gates says. “They watch the video and write the data in field notebooks as if they were in the field working in a small group. They analyze the data and perform operations on it with all the uncertainty of a real field trip.”

Geology student Nikita Bendre says the videos were a very creative solution, sometimes feeling like she was wearing a virtual reality headset. Although a video accurately maintains the educational aspect of the field trip, she really missed having the chance to “physically feel different rock textures and collect the measurements—a fun learning process that gave me the opportunity to apply the theories learned in the classroom to the real world.” Gates agrees, saying, “Nothing replaces person to person.”

Bendre encountered other complications. “Internet and Webex conferencing connectivity issues are the common ones,” she says, “but the most difficult challenge is finding a quiet place to sit and ‘attend’ classes. My dad has daily business calls when I have my classes, so it is very easy to get distracted by the littlest noise.”

Heather Hart, a Mason Gross School of the Arts sculptor and interdisciplinary artist, faced the daunting challenge of teaching an undergraduate practicum course, “Sculpture II B,” for which “no video will substitute entirely for hands-on training” in skills like welding or safely using a table saw. “These are critical for a sculpture degree,” she says, “and my challenges are how to give students access to the information and skills they need to move forward in their studies and not fall behind. For sculpture, that’s not an obvious path. Most students don’t have the space to make work they normally would and don’t have even basic tools at their homes.”

Without access to the art studios and supplies at Rutgers, Hart continued the class’s study of objects via deconstruction and reconstruction, using the Zoom conferencing platform to interact with one another. “But instead of sourcing materials from school, the students are raiding their pantries, recycling bins, and storage spaces for things to transform,” she says. For Hart, this was the clear upside: “They learn not only formal skills and resourcefulness, but also the importance of adapting and flexibility as an artist. In the real world, we are constantly given constraints, and if they can use this trying time to seed their ideas and their work, they will come out of it as stronger thinkers and stronger artists.”

While a big advocate of the access that remote teaching can provide in certain situations, Hart says she is “also a skeptic because of the privilege required to access the online teaching platforms we have. Many of our folks can’t use the internet without a public space like a library. So, what happens when the libraries are shut and we are asked to stay indoors? Internet should be a public utility.”

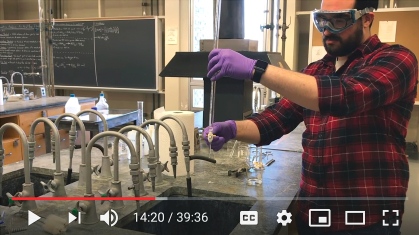

While Gates’s and Hart’s specialized hands-on classes had small enrollments, 13 or fewer students, Rutgers University–New Brunswick chemist Michael Vitarelli’s “Introduction to Experimentation” is a core chemistry course enrolling more than 1,000 undergraduates across 50-plus lab sections. Before the pandemic, the lab sections, led by a corps of teaching assistants (TAs), met once a week in person, using the Sakai learning management system—software for online administration and delivery of educational courses—only for course announcements, grades, and documents. To handle the massive number of students, Vitarelli, like Gates, turned to virtual-experience videos, uploaded to YouTube. In the videos, students see and hear TAs conduct experiments, present data, and discuss safety. Students watch and submit their prelabs and postlabs to their TAs.

Abigail Seo, one of Vitarelli’s TAs, says she grappled especially with “grading labs consistently and still providing feedback immediately enough to students.” With students, many in different time zones, needing flexible schedules to do their work, Seo often waited days for all the labs to be handed in before starting to grade. Fair grading is best achieved, she says, when all student work is reviewed in one sitting.

Vitarelli says that although keeping up with students’ emails and Sakai chat queries was a seven-day-a-week challenge, the core goal was designing 12 virtual labs that mimicked a normal environment. “Part of the purpose of a lab class is to prove to the students that a concept, taught in a lecture, actually materializes in reality,” Vitarelli says. In the final lab of the course, he planned to demonstrate the concepts of paramagnetism and diamagnetism—how materials with different electron configurations respond to magnetic fields. “It is my hope that the students will believe the results from the virtual lab,” Vitarelli says. “If they do, I will be proud of this.”

As Vitarelli worked to perfect his virtual labs, an intensive traditional humanities seminar was presenting a different set of obstacles for Richard L. McCormick, a distinguished professor of history and education as well as president emeritus of Rutgers. McCormick’s mission was to find a new way to teach “Presidential Elections in United States History,” an interdisciplinary honors class, allowing it to maintain the essence of seminar learning.

McCormick turned to the “terrific” staff at Digital Classroom Services (DCS)—a Rutgers University–New Brunswick unit that manages more than 300 high-tech learning spaces—who helped him quickly get up and running. DCS focused on showing faculty like McCormick how to use its learning spaces as studios for course preparation and delivery, says associate director David Wyrtzen. “Our team really rallied by engaging closely with faculty, being flexible, and thinking outside the box—all while dealing with major disruptions to their own lives.”

The studio approach worked for McCormick. “I prepare for my classes just as before—materials like readings and videos were, and still are, posted on our class website on the Canvas learning management system,” McCormick says. “But now instead of meeting my students twice a week in our former seminar room, I go to an empty classroom in the Rutgers Academic Building and sign on with my students. We all can see and hear one another. It’s a bit awkward but manageable.

“In almost every class,” McCormick continues, “we talk about one or more historical elections and we review and discuss the latest developments in the 2020 election campaign.” Important tweaks included revising sources required for final research papers, so each topic could be researched entirely on the internet.

Remote learning worked for McCormick and his students, but was not ideal. “My students and I are all taking the class just as seriously as we did before,” he says. “Almost every student attends every class, and I do my best to keep it upbeat and fun and engaging, but I can’t wait to be teaching in a classroom again.”

Oscar Holmes IV, a management professor at Rutgers University–Camden, says his experience teaching “Conflict Resolution and Negotiation” online for several semesters eased the transition to remotely teaching two sections of “Organizational Behavior.” Holmes got started by surveying the class about synchronous or asynchronous class meetings. Synchronous classes offer lectures, discussions, and collaboration at fixed times for all students; the advantage is replicating something closer to the in-person class experience. Asynchronous classes offer greater flexibility, with lectures, demonstrations, chats, and due dates at times most convenient for students but at the expense of the more shared experience.

“The majority of class sessions are asynchronous because many students and myself are juggling many different responsibilities, like child care, where we can’t commit to a specific time to meet twice a week, every week,” he says. “But two synchronous classes give us a time to reconnect with one another in real-time and do activities that don’t lend themselves as well to asynchronous instruction.” For asynchronous meetings, Holmes records a video with the main takeaways from the class assignments and “posts a transcript of the video in case people have connectivity issues and just want to read what I state in the video.” For synchronous meetings, he uses a webcam and the Canvas learning management system with its “chat, video, screen sharing, white board, and audio capabilities.”

Student Tiffany Mendoza appreciates Holmes’s efforts. “He accommodated the students’ needs by surveying the class’s online preference on how classes would run. It is mostly asynchronous to accommodate students struggling with issues such as child care, sharing of one device, or Wi-Fi connectivity.”

Like others, Holmes faced the reality of teaching a course that ordinarily featured interactive teamwork assignments as well as fieldwork. One section of “Organizational Behavior” has a civic engagement component where students work with local nonprofits, raising funds and awareness. “This had to cease immediately,” Holmes says, with students losing out on learning experiences and nonprofits losing out on the benefits of students’ contributions.

Digital Classroom Services helped faculty members utilize Rutgers’ growing number of high-tech learning spaces as studios for course preparation and delivery—an alternative to teaching from home.

Writing lecturer Marie Scarles, who teaches “English Composition II,” a course required for all Rutgers–Camden undergraduates, also weighed synchronous versus asynchronous instruction. The deciding factor came down to the needs of her students outside of class. “I have a number of students who are considered essential workers, and I decided the class would run more smoothly if the course deadlines became flexible,” Scarles says. Her students collaborate to create small group biweekly presentations on readings, something they used to present in class, but instead post to and discuss on Sakai.

Tiernan Johnson, a member of the Scarlet Raptors men’s soccer team, is one of Scarles’s students who is an essential worker. He found the transition to remote learning difficult. “Although my professors have been a lot of help, I have been under stress personally at home with getting my work done and balancing my time.” Johnson is an employee at Wawa and deemed essential for serving first responders. His mother, too, is an essential worker, employed by the grocery store at a nearby military base. Every day, he is concerned that either of them might get infected with COVID-19 and bring it home. During this trying period, Johnson was grateful for his professors who were great at communicating, providing updates, and being flexible.

“Typically, I’d say working a job, doing work for school, and training to stay in shape for soccer would just be the life of a student-athlete,” he says. “But in these circumstances, there is added stress and concern about everything that’s happening. I’m taking it a day at a time.”

Rutgers has risen to the challenge, embracing a formula that leads to remote teaching and learning success in the world of COVID-19 crisis control: taking advantage of technology to advance higher education while appreciating the human element—communication, flexibility, and understanding. The effective emergency response of the university to provide remote educational options raises another question: with no reliable predictions on the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic, how long will remote instruction be the new normal? Summer session has already been declared an all-remote season of learning. Will this extend to the fall or beyond? The university is looking at several options, including a partial opening and full-time remote learning. To prepare for the likelihood of either one of these scenarios, faculty are getting additional guidance and tools for doing this more smoothly.

Whatever the coming months bring, there is little doubt that the learning access and options powered by high-tech innovations will play an increasingly important role in university life. “Information technology has been and will continue to be a critical, strategic component to this institution, no matter what mode we operate in,” says Michele Norin, senior vice president and chief information officer, “especially remote mode.”