Life in DC Under Lockdown

Alumnus and freelance journalist Rich Shea shares his account of life in the nation's capital during the fraught two weeks leading up to Inauguration Day.

Walls.

Barricades.

Fences.

When I moved to Washington, D.C., five years ago, they were all part of the landscape, a collection of mostly post-9/11 precautionary measures intended to repel potential acts of terrorism. But for a suburbanite moving to the Capital, these fixtures were just backdrop and easily skirted as I worked my way, usually on foot, from one monument, museum, or neighborhood to another.

One, it turns out, was a stroke of genius. The stretch of Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House was closed to vehicular traffic in 1995 after the bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City. It now served as an extension of nearby Lafayette Square, a park where people could snap photos, peacefully protest, or simply admire the north portico of "the people's house."

It’s also where, a year and a half ago, D.C.’s backdrop began moving to the foreground. In the summer of 2019, after decades of complaints about the ease with which the daring or deranged could jump the White House fence, a heightening project began. The following June, as Black Lives Matter protests heated up, Lafayette Square was fenced in completely.

Meanwhile, across town, not far from where I live, a perimeter of sorts was established around the U.S. Capitol, mostly by the presence of waist-high barricades and police officers on the east and west entrances’ steps. Annoying? Yes. But for the sake of keeping the peace, you play by the rules and occasionally offer a wave or a “thank you” to the men and women simply doing their job.

What you don’t imagine is what ended up recently taking place and turning D.C. into a militarized zone.

A Day of Infamy: January 6

As a freelance journalist and communications specialist, I keep an eye on the news and was aware of the rumblings about potential violence on the day that Congress was set to count the Electoral College votes: January 6. I had also witnessed, back in November, a Stop the Steal protest in front of the Supreme Court, just across the street from the east entrance of the Capitol building. That day, November 14, was something of a wake-up call. Over the previous few years, far-right groups had staged protests in D.C., with their numbers outmatched by nonviolent, albeit vociferous, counter-protesters.

But standing not far from the Supreme Court, I watched with trepidation as hundreds of stop-the-stealers who’d marched from Freedom Plaza, about a mile and a half west, streamed onto 1st Street with placards raised, flags flying, and epithets hurled at counter-protesters, who, this time around, were the ones outnumbered. I kept my distance for two reasons. Even though police officers were present, they, too, were outnumbered, and violence was a possibility. Plus, we were in the middle of a pandemic, and most of the protesters were unmasked.

As the throng increased in size and gathered in front of the Supreme Court, I stuck around long enough to hear the rallying point’s first speaker, who, after taking the podium, incited the crowd by spewing conspiracy theories and claiming that a revolution as significant as that of 1776 was at hand. Which is when I said to myself, OK, I’m done, then spent the next hour or so walking off what I’d just witnessed. Like anyone living in D.C., I was accustomed to marches and protests. But the worst I’d witnessed on 1st Street were no more than spirited shouting matches between opposing factions. And two months prior, it was the setting of a solemn, flower-strewn memorial for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Supreme Court Justice who had once been a professor at Rutgers Law School in Newark.

This time, though, the intense frustration and anger of the stop-the-stealers brought me face-to-face with a huge cultural divide in this country—a divide lodged in my mind when I got on a business call on January 6. Five minutes earlier, I’d watched some of the president’s speech outside the White House during which he continued to challenge the election results and encourage his followers to march to the Capitol.

And after I ended my call, more than an hour later, I got a text from a friend and neighbor, saying: “They’ve breached the Capitol.”

For a second, I thought, Who? And then I knew—and turned on the TV and watched what everyone witnessed, the scenes of mayhem, broken glass, and tear gas, of protesters streaming into the east and west entrances of the Capitol, some fanning across Statuary Hall, a truly historical, and arguably sacred, place where those represented in marble and bronze range from George Washington to Rosa Parks.

It was at that moment I screamed at the TV, “How the hell did they get in!”

Then, to my dismay, I noticed that the few police officers in the hall were doing nothing to escort the intruders out. Of course, none of us, in those early moments, knew the extent of the breach or how violent some of the confrontations in and outside of the Capitol were. But having witnessed the law-enforcement measures taken to hold back Black Lives Matter (BLM) protesters last summer, I found it mind-boggling that local and federal forces hadn’t prepared for what everyone knew might be a violent protest.

For the next couple hours, as I texted friends and paced my living room, I was just as perplexed by the lack of help from outside the Capitol, help we now know was being offered by at least one nearby governor, only to be rebuffed or ignored. It wasn’t till about 5 p.m. that day, after extensive damage and lives lost, that help arrived and the building was finally cleared. I fell to my knees at that point and wept.

I should mention that after George Floyd’s death in late May, I participated in a BLM protest just off Lafayette Square, the park near the White House. I was masked, as were most protesters, but I still tried to keep my distance while eyeballing possible escape routes. There were tense moments, when protesters and police jostled each other and tear gas was dispersed. There were even a few agitators taunting both police and protesters—one, a young man claiming he could spot “undercover cops” among the throng.

But during that protest and others in D.C. over the past few years, the agitators amounted to an almost insignificant minority. And when it came to subsequent BLM protests near Lafayette Square—countered first by riot police and then, after the president’s visit to St. John’s Church, the construction of an eight-foot fence around its perimeter—anyone seeking to breach anything didn’t have a chance. Which is the point: those protesters were only seeking to be heard.

On January 6, amid the mayhem, it was difficult to know the rioters’ exact intent. What we knew was that an extremely thin blue line of Capitol police was left to fend for itself against an enraged mob, some of its members evidently planning a full-scale attack while others were encouraged to join in. And as I watched, I couldn’t help but remember what I’d witnessed in November—the frustration, the anger, and, yes, the hatred. It had been building for months, if not years, and had finally boiled over.

And Inauguration Day was just two weeks away.

The Days in Between

The day after that November rally, I needed, more than anything, to see both the Supreme Court plaza and 1st Street devoid of protesters. When I did, and the sole remnant was a half-torn, homemade “Stop the Steal” sign, I was relieved. The same urge to see order restored struck on January 7, when I found myself walking to the Capitol reflecting pool, which lies behind the building’s west entrance.

Once again, relief. There were maybe two dozen stop-the-steal stragglers, some waving flags, one with a bullhorn, most chatting with one another as the driver of a panel truck emblazoned with “Trump Won” honked his horn while skirting the National Mall. The Capitol barricades chucked aside by protesters a day earlier were now replaced by eight-foot fences and National Guard troops and other law enforcement personnel. Just up the hill, workers repaired the damage done to scaffolding installed for inaugural preparations. Overnight, the U.S. Congress had, indeed, resumed its certification of the Electoral College results and pronounced Joe Biden president, allowing for Inauguration Day preparations to proceed.

Although DCites were in a daze, it was reassuring to see fences popping up around not only the Capitol, but also the half-dozen Senate and House office buildings and the Library of Congress, home to national treasures like the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address. Even where fences weren’t appearing, there was the National Guard, mostly friendly and game for selfies. I felt like saying, “Where were y’all when we needed you?” but these young men and women weren’t to blame. And now they were keeping us, and democracy, safe!

What few, if any, of us knew was that it was just the beginning of a military and law-enforcement buildup historical in scope.

The last day that felt close to “normal,” even liberating, was January 10. I was with my friend, walking along the mall, where fences had been erected around the grassy areas. But the weather—sunny, mid-50s—was close to perfect as a good-sized, mostly masked crowd was walking the gravel paths. At one point, we came across 10 or so people collecting trash and removing stickers from lampposts. I’d later learn, through The Washington Post, that they were members of Continue to Serve, a coalition of military veterans who, disgusted by the behavior of vets who’d taken part in the insurrection, were cleaning up the detritus that the stop-the-stealers had left behind.

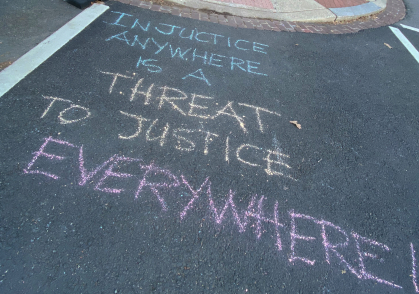

Just across from the mall, waist-high barricades had been placed around the Capitol’s reflecting pool area, with openings along pathways permitting limited access. A stretch of the barricades was adorned with an encouraging collection of handmade signs. One read “Democracy is Diversity,” another “We the People Choose Democracy,” and another “Never Again, Defend Democracy.”

The sense of relief didn’t last. Soon, we were all hearing news that other groups were planning armed protests in not only D.C., but also state capitals across the country. Local and federal law enforcement responded by erecting higher fences in the city and cordoning off the entire mall area.

The first thing we noticed were the traffic jams. By mid-January, once-quiet streets were bottle-necked with cars and trucks, in part because more than a dozen Metro stations were closed and buses rerouted. Even some of those streets not fenced-in were blocked by cop cars, allowing only residential traffic. A neighbor half-jokingly shared that overnight his car had been hemmed in by a police barricade. My friend and her sister took an Uber to a restaurant across town for an al fresco dinner, only to discover after their meal that fresh fencing now prohibited car service. So, with directions provided by police, they zig-zagged their way back home on foot.

On the one hand, I was grateful a coordinated effort was finally being made to protect the country’s seat of power. But these security measures left the rest of D.C. seemingly open to attack, with residents wondering, If I want to escape, how? As access routes to major highways were blocked and bridges closed, our options narrowed. And the neighborhood’s social media chatter included messages about stocking up on food and, just in case, packing “go bags” for quick, if almost-impossible-to-navigate exits.

What the hell? I thought. First a pandemic, then an insurrection, and now this?

At the same time, the military buildup was a source, at least initially, of fascination. Like other locals, I spent a few afternoons walking around Capitol Hill, Union Station, and, during one excursion, the White House, taking photos and marveling at the speed and efficiency of the operation. No more waist-high barricades and smiling troops—only grated fences and body-armored sentinels.

And gates allowing authorized vehicles in and out of staged areas.

And white tents sheltering military police and Secret Service.

And razor wire.

Friday, January 15, was the last time I had access to two significant thoroughfares. The first, just off Lafayette Square, is now known as Black Lives Matter Plaza. It’s the two-block stretch of 16th Street NW that on June 5, under orders from D.C.’s mayor, Muriel Bowser, was emblazoned in yellow paint with “Black Lives Matter” by the city’s public works department. I was there that first day and have visited a few times since. To me, it’s always felt like a block party featuring music, dancing, peaceful protests, and placards extolling diversity and equality. Now, it was all but shut down, with concrete blockades preventing vehicular traffic and maybe a dozen people wading among BLM banners and flags.

From there, I walked south, along 15th Street NW, past boarded-up shops, hotels, and restaurants, to Pennsylvania Avenue, which surprisingly was open to foot traffic, though there wasn’t much of it. Pennsylvania Avenue is the route the stop-the-stealers took from the White House to the U.S. Capitol January 6. Traditionally, going in the other direction, it’s also the parade route for a just-inaugurated president being driven to his new home. For security reasons and the absence of spectators, President Biden and Vice President Harris would take another route on January 20. But the lampposts along Pennsylvania were still festooned with American flags, providing me with a surreal, 10-block parade of my own, as I snapped photos and passed the odd pedestrian or police car.

The end of the line was 3rd Street, where a wire-and-plexiglass fence under construction afforded me a grand view of the Capitol’s west entrance, its archways—recently the scene of a riot—hung with five huge American flags for the inauguration.

Over the next several days, as D.C. made it through the weekend and Martin Luther King Jr. Day without incident, Pennsylvania Avenue and blocks’ worth of surrounding streets were cordoned off. National Guard troops continued to arrive, literally, by the busloads, and the press, both foreign and domestic, positioned their cameras on street corners with the Capitol dome as backdrop.

And I was angry—not at the cops or the military, who, if anything, were going above and beyond the call of duty, but at those who’d chosen the undemocratic route of trying to take what was not rightfully theirs. They’d not only horrified the nation; they’d robbed D.C. residents of what should have been a much-needed, if even brief, celebratory period in our lives.

So, the novelty had worn off. Our universe had shrunk considerably. Navigating security perimeters was now a daily grind. The one upside? A potentially safe and secure inauguration.

Inauguration Day

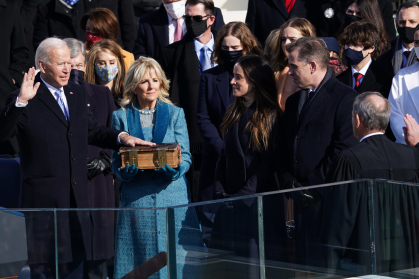

Inauguration Day, as we now know, was a success. The ceremony, overlooking a “Field of Flags” art installation on the mall, went a long way in repairing, at least temporarily, a battered nation. Because I wasn’t able to get close to the Capitol and didn’t want to miss anything, I watched it all on TV while wondering how much longer our law-enforcement friends might be staying in town.

I also remembered something.

D.C. is a city brimming with memorials—some well-known, most of them not. Just a couple days before inauguration, I stumbled across one that hadn’t been fenced in and I’d never heard of—The American Veterans Disabled for Life Memorial. Opened in 2014, the granite-and-glass mix of sculptures, images, and inscriptions is a sobering site, a reminder of the sacrifices made by 4 million veterans seriously injured in the line of duty. It also stands less than half a mile from where the inauguration and the storming of the Capitol took place.

I couldn’t help but think that those honored by the memorial would have preferred a peaceful transfer of power.