Terror Medicine: Treating the Injured in Terrorist Attacks

A Rutgers emergency medicine expert says Paris, San Bernardino and more potential violence demonstrate a need to educate first responders and specialists

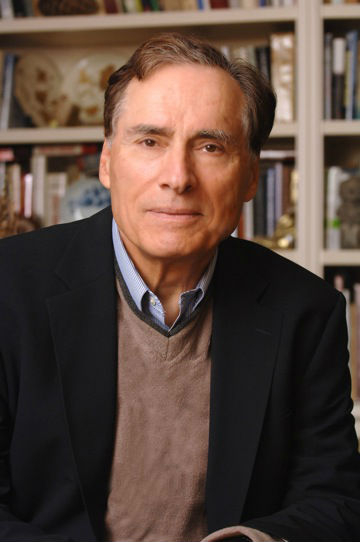

Leonard Cole, director of terror medicine and security in the Department of Emergency Medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, recently testified with former Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge and former Sen. Joseph Lieberman in a hearing on bioterrorism conducted by the House Committee on Homeland Security. Cole is now preparing to deliver his two-week terror medicine elective to final-year NJMS medical students for the fourth time. The tragic terror-related events of recent weeks have given Cole greater resolve to have similar courses taught in more locations nationwide. Rutgers Today recently spoke with Cole about the need to prepare those in the medical community for issues they’d face should a terrorist attack or other incident result in mass casualties.

Rutgers Today: What is key to treating people injured in a terrorist attack?

Cole: When terror attacks occur, health care workers must think quickly about how to respond, particularly the first responders. If a bombing occurs, the instinct is to rush to the location and start treating the injured at the site. But we’ve learned that except for heavy bleeding and other life-threatening injuries, it can be better to “scoop and run” – that is, to quickly transport the wounded to a hospital for treatment because more bombs may be targeting the area just hit. It’s a strategy we’ve learned from events in Israel.

Rutgers Today: Should the focus of teaching terror medicine be first responders?

Rutgers Today: Your terror medicine course teaches how to deal with poison gas, how to respond to a chemical or biological incident and how to effectively manage large numbers of casualties. What has changed most as your course has evolved?

Cole: Ebola, which in the past year caused more than 10,000 deaths in West Africa, became the biggest new concern in terms of preparedness. Ebola is highly contagious and the virus is deemed a potential biological weapon, though the recent outbreak was of natural cause. Still, people were petrified about the possibility that they or others they knew had been exposed. Nearly every major biosafety lapse had some form of human error at its core. Our experience with Ebola underscored the need to better understand and prepare for what can go wrong, whether by human error or intentional harm.

Rutgers Today: How can you deliver the terror medicine expertise you’ve gathered to more people in health care?

Cole: We train hospital workers how to react in the event of a fire or to a patient with contagious infection. Doesn’t it also make sense to train workers to respond to the distinctive needs associated with terrorist attacks? Medical and nursing schools should include aspects of terror medicine in their curricula. We should explore how some of the federal and state government resources dedicated to protecting the U.S. against biological agents could be allocated to education on the broader field of terror medicine. The net result would be enhancement of overall preparedness.

For media inquiries, contact Jeff Tolvin at 973-972-4501 or jeff.tolvin@rutgers.edu