Sea-Level Rise in 20th Century Was Fastest in 2,000 Years Along Much of East Coast

Global increase from melting ice and warming oceans is most significant change since 1800

The rate of sea-level rise in the 20th century along much of the U.S. Atlantic coast was the fastest in 2,000 years, and southern New Jersey had the fastest rates, according to a Rutgers-led study.

The global rise in sea level from melting ice and warming oceans from 1900 to 2000 led to a rate that’s more than twice the average for the years 0 to 1800 – the most significant change, according to the study in the journal Nature Communications.

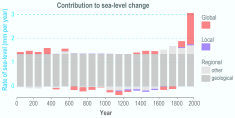

The study, for the first time, looked at the phenomena that contributed to sea-level change over 2,000 years at six sites along the coast (in Connecticut, New York City, New Jersey and North Carolina) using a sea-level budget. A budget enhances understanding of the processes driving sea-level change. The processes are global, regional (including geological, such as land subsidence) and local, such as groundwater withdrawal.

“Having a thorough understanding of sea-level change at sites over the long term is imperative for regional and local planning and responding to future sea-level rise,” said lead author Jennifer S. Walker, a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University–New Brunswick. “By learning how different processes vary over time and contribute to sea-level change, we can more accurately estimate future contributions at specific sites.”

Sea-level rise stemming from climate change threatens to permanently inundate low-lying islands, cities and lands. It also heightens their vulnerability to flooding and damage from coastal and other storms.

Most sea-level budget studies are global and limited to the 20th and 21st centuries. Rutgers-led researchers estimated sea-level budgets for longer time frames over 2,000 years. The goal was to better understand how the processes driving sea level have changed and could shape future change, and this sea-level budget method could be applied to other sites around the world.

Using a statistical model, scientists developed sea-level budgets for six sites, dividing sea-level records into global, regional and local components. They found that regional land subsidence – sinking of the land since the Laurentide ice sheet retreated thousands of years ago – dominates each site’s budget over the last 2,000 years. Other regional factors, such as ocean dynamics, and site-specific local processes, such as groundwater withdrawal that helps cause land to sink, contribute much less to each budget and vary over time and by location.

The total rate of sea-level rise for each of the six sites in the 20th century (ranging from 2.6 to 3.6 millimeters per year, or about 1 to 1.4 inches per decade) was the fastest in 2,000 years. Southern New Jersey had the fastest rates over the 2,000-year period: 1.6 millimeters a year (about 0.63 inches per decade) at Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge, Leeds Point, in Atlantic County, and 1.5 millimeters a year (about 0.6 inches per decade) at Cape May Court House, Cape May County. Other sites included East River Marsh in Guilford, Connecticut; Pelham Bay, The Bronx, New York City; Cheesequake State Park in Old Bridge, New Jersey; and Roanoke Island in North Carolina.

Rutgers coauthors include Robert E. Kopp, a professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers University–New Brunswick and director of the Rutgers Institute of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences; and Erica L. Ashe , a postdoctoral scientist in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences. Scientists at Nanyang Technological University, Maynooth University, the University of Hong Kong, Bryn Mawr College, Durham University, Liverpool Hope University and East Carolina University contributed to the study.