Research Team Studying Aging and Disease Adapts During Pandemic

After decades of investigating the molecular mysteries behind aging and disease, Monica Driscoll last spring faced a puzzling new problem.

How would her team of nearly two dozen researchers – comprising one of Rutgers University’s largest and most prominent science labs – continue its work during Covid-19?

Driscoll, a molecular neuro-geneticist in the School of Arts and Sciences at Rutgers-New Brunswick, seeks to discover the ways in which humans might extend healthy lifespan. Her research tackles illnesses like Alzheimer’s disease and ALS and draws extensive funding from the National Institutes of Health.

It’s not a job that can be handled over Zoom.

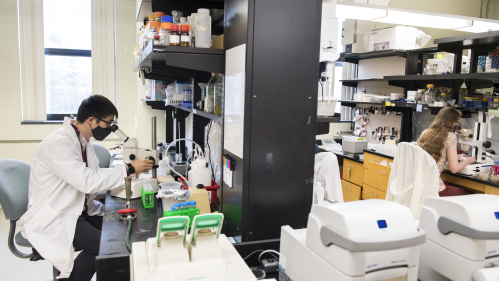

Yet her team has worked out a system to continue experiments while respecting social distancing protocols. Researchers stagger their lab times and have spread out through Nelson Biological Laboratories, while also finding innovative ways to work online.

“We figured it out,” Driscoll says. “We bring people into the lab in ways that they can avoid each other. It takes mega-organizing. But we made it work.”

There are plenty of difficult days. Lab manager Mary Anne Royal had to drive home with a package of worms to ensure the sample was shipped. Lab assistant Elaine Gavin, facing disrupted supply chains, is often on the phone tracking down new sources for everyday lab materials. And at Thanksgiving, Driscoll had to forgo her tradition of bringing in a chocolate turkey, opting instead for turkey-shaped lollipops.

“Little things like that challenge our connection to one another,” Driscoll said. “In a group where we have a common purpose, we work hard, but we also have fun.”

The close-knit culture, which has informed the lab’s success over decades, was especially vital in 2020.

“This lab is more cooperative than competitive,” says Royal, who has worked with Driscoll for more than 20 years. “Faced with this incredible challenge, we did what we always do: we talk to each other, we collaborate, and we figure it out.”

Driscoll, a Douglass College graduate, received her Ph.D. from Harvard University and is a Distinguished Professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry. She did her post-doc at Columbia University, studying under 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry recipient Martin Chalfie.

“In a beautiful way she exemplifies the passion for science that we all feel,” Royal says. “Monica wouldn’t notice if the walls blew down in her office as long as she could keep doing science.

“This year has been all about finding the way to do what we love in spite of another hurdle.”

In carrying out its mission, the lab uses advanced equipment, like a laser microscope that cuts nerve cells. Yet the actual subject of the experiments might come as a surprise to those outside the sciences.

The intense focus is directed upon a two-millimeter worm, known as C. elegans.

Researchers perform genetic engineering on the worm, observing its movements and examining the behavior of its neurons. In 2019, Driscoll put 3,600 worms aboard the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket to the International Space Station to study muscle decline on space flights.

“We have a fundamental interest in aging and neurodegeneration, and the way we approach it is through this tiny worm,” Driscoll says. “We can use genetic tricks to find the mutant that cures its own disease, and then we have the tools to figure out how it did that.”

Eddie Chuang engineers the worms to express proteins associated with ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease.

“I am looking at how their neurons respond,” said Chuang, a post-doc. “How do they mitigate the danger?”

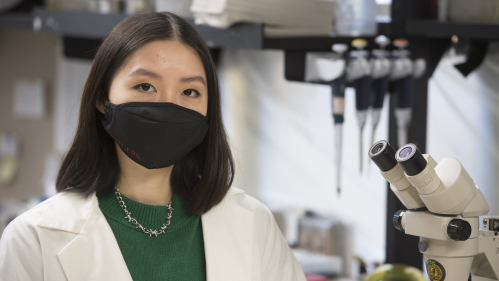

Julia Li, an SAS senior, said she was drawn to the team in part because she had a relative with dementia.

“What this lab does is significant in the medical field,” she says. “And it is significant in my life.”

When the pandemic struck New Jersey, the lab scrambled to shut down, and a host of experiments were lost.

As Rutgers began allowing labs to reopen at partial capacity, the team developed an extensive calendaring system in which people reserve their bench time as well as equipment. There is a strict one person-per-bay policy, with dividers hanging between workstations. Lab members work out their schedule with their neighbor.

“I've always been a mid-afternoon to late-night worker, while my bay mate is here earlier in the morning,” says graduate student Joelle Smart.

The team also found ways to work online that utilize the techs who normally prepare lab plates.

“Instead of having researchers look at thousands of cultures in the lab, we photographed the cultures and made the images available online,” Driscoll said. “Then our media technicians learned fast how to recognize what we were searching for.”

Nevertheless, science doesn’t work according to shifts, and the schedule sometimes has to be ripped up and revised. And while Driscoll holds remote meetings to discuss research, there is something lost through videoconferencing, she said.

“The spontaneous interactions, the bumping into each other — that’s very important for science communication,” she says. “On Zoom we can still talk about experiments, but I have to schedule it.”

All told, Driscoll says, the advancement of science will continue to require face-to-face human interaction. And she is relieved to see vaccines on the way.

“We realize how just the casual ways we connect are important in transmitting information,” she said. “We are coping. But it’s great to know that there is a sense of an end in sight."