Professor Examines the Rise of Counterfeiting in China

Criminal Justice professor’s book explores the emergence of the lucrative but illicit business

Counterfeiting tops the list of organized crimes worldwide, raking in nearly half a trillion dollars in 2019 and causing U.S.-China tensions over intellectual property theft.

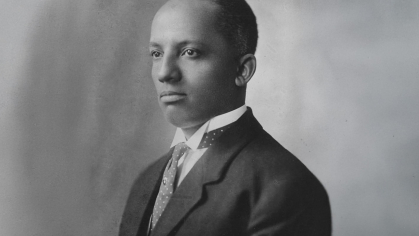

Ko-lin Chin, professor of Criminal Justice at Rutgers’ School of Criminal Justice, has been conducting research on organized crime for more than 30 years. In his new book, Counterfeited in China: The Operations of Illicit Businesses, Chin investigates the lucrative industry and its emergence in China.

Chin has written extensively on issues related to Chinese crime groups and networks, including Chinatown gangs, human smuggling organizations, organized crime in Taiwan and China, the heroin and methamphetamine businesses in Myanmar and China, and sex trafficking networks in Asia and the United States. His new book features the first empirical research on counterfeiting luxury goods in China, based on face-to-face interviews with counterfeiters. The book answers crucial questions about counterfeiting and its effect on the economy.

Why is there such a demand for counterfeit goods?

Worldwide, many people cannot afford to buy genuine luxury items but would like to possess them. As a result, they buy what they can afford: fake items that look exactly like the authentic items but cost only a fraction of the genuine goods. In addition, the supply chain for counterfeit goods is deeply embedded in the supply chain for legitimate goods, and the ease of distributing counterfeit goods also fuels the demand. The rise of e-commerce platforms also plays a major role in allowing buyers to purchase counterfeits from their homes.

What role do Chinese authorities and other parties in the war against counterfeiting play?

Local Chinese authorities have benefited from the counterfeiting business indirectly. They are the landlords of most of the retail and wholesale markets for counterfeit goods, and they are guaranteed to collect their rents regardless of whether individual counterfeiters make money. Thus, even though the central government in Beijing may want to crack down on counterfeiting in the face of international pressure, local authorities may want to protect the benefits they and the local businesspeople obtain from the flourishing counterfeiting industry. There are also many stakeholders in the war against counterfeiting: international brand owners, multinational law firms, major private investigative businesses, and local anti-counterfeiting investigation offices. Though they try to stop counterfeiting by working either independently or in collaboration with officials, their efforts have yielded limited results due to many factors.

What prompted your interest in writing this book?

Counterfeiting, as a new form of transnational crime, is alleged to be dominated by Chinese organized crime groups and protected by Chinese government officials. I wanted to find out whether this was true. I also wanted to explore the modus operandi and the risk management strategies of counterfeiters, the economic aspects of counterfeiting, and the demand side of counterfeit goods.

Why is this an important issue today?

The current tension between the United States and China is fueled partly by U.S. allegations that Chinese authorities are either directly engaged in the theft of intellectual property or indirectly protecting it. Yet there is almost no empirical research on this issue, and we know very little about the realities of the counterfeiting business.

What is the economic cost of counterfeiting? Who does it hurt and why should the public be concerned?

The economic cost of counterfeiting may have been overestimated by government officials, law enforcement agencies, anti-counterfeiting investigation firms, and brand owners. We do not know whether brand owners suffer lost sales due to counterfeiting. We also do not know how much counterfeiting is deceptive (i.e., buyers don’t know they’re buying counterfeits) and how much is non-deceptive (i.e., buyers know they’re buying fake goods). The public should be concerned mainly when counterfeit goods (i.e., food, machine parts, medicine, cosmetics) are hazardous to their safety or health.