Rutgers professor donates Polish film posters to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

As a collector, Richard Koszarski was always gathering something – stamps, baseball cards, or American movie posters.

But it was the roll of posters that his father brought back from Poland in the 1960s that would lead to a lifelong obsession with Polish culture and art, and a collection of more than 6,000 posters that provide a window into post-World War II Poland.

Koszarski’s father, who was born in New York but raised in Poland, still maintained strong ties to his homeland after returning to the U.S. before the war. An importer by trade, his father began importing Polish films during the late 1960s. He worked directly with Film Polski to bring these films to predominantly Polish neighborhoods in New York and New Jersey.

“My interest went beyond a souvenir from The Graduate to understanding the peculiar Eastern European symbol systems employed to illustrate these films,” says Koszarski, an associate professor of English and film studies in the School of Arts and Sciences.

His father’s connections within the Polish film industry brought in a fair amount of rare editions, and Koszarski also acquired some vintage pre-war posters that were sent to the United States in the 1930s.

After retiring in 1979 and moving back to Warsaw, his father devoted much of his free time to finding more posters. “I would send the cash, and he would track down sources through newspaper ads, personal referrals, and intuition,” Koszarski says.

Their exchanges became so regular that customs agents already knew what to expect when they inspected the packages his parents would send to the United States. Koszarski estimates that at the height of their search, his parents shipped more than 5,000 posters.

At some point, for Koszarski, collecting moved from hobby to obsession. “It became clear that we had a brief window of opportunity to assemble a comprehensive collection of post-war Polish poster art – and we decided to take advantage of it,” he says.

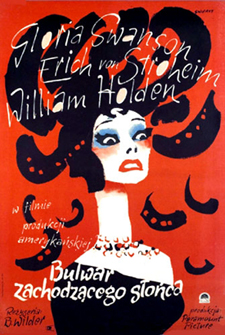

What makes these Polish film posters special is their artistic and cultural value. After World War II, the communist economy in Poland didn’t need film posters as advertisements because there was no competition. Instead, the Polish government saw posters as announcements, and used poster design commissions as a form of arts subsidy. This gave poster artists freedom to interpret the movies and create graphic representations rather than focus on selling tickets.

“Very seldom did you see portraits of movie stars or other conventional images,” Koszarski says. “These posters represent an artistic outlet – one of the few that was available in a time of censorship. The posters became a way of representing not only the artistic aspirations of a country but also the social and cultural mood of the time.”

Sometimes artists didn’t even watch the films. They would read a summary of the movie or look at photos. “It was more about the artist’s take on say, Midnight Cowboy. The styles differed over the years, but these posters would incorporate very sophisticated symbol systems which sometimes had political subtext, and sometimes were simply very personal representations of the artists own feelings,” Koszarski says.

Koszarski’s selection of unique post-World War II film posters from the late 1940s into the 1970s attracted the attention of the Margaret Herrick Library of the prestigious Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

The curators at the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy sent a representative to look over his entire collection for three days before deciding on what pieces to include.

Koszarski was happy to share his collection with others. “You can read about collections like these in books, but we wanted something to be here,” he says. “Something people in the U.S. could see.”

There was one poster; however, Koszarski couldn’t part with. “I wouldn’t let go of my Sunset Boulevard. It was a very hard poster to find, and I’ve done a lot of work on Erich von Stroheim. I have it sitting here next to me in a frame. I let them take almost everything else.”