Mega-Cloud from Canadian Wildfires Will Help Model Impacts of Nuclear War

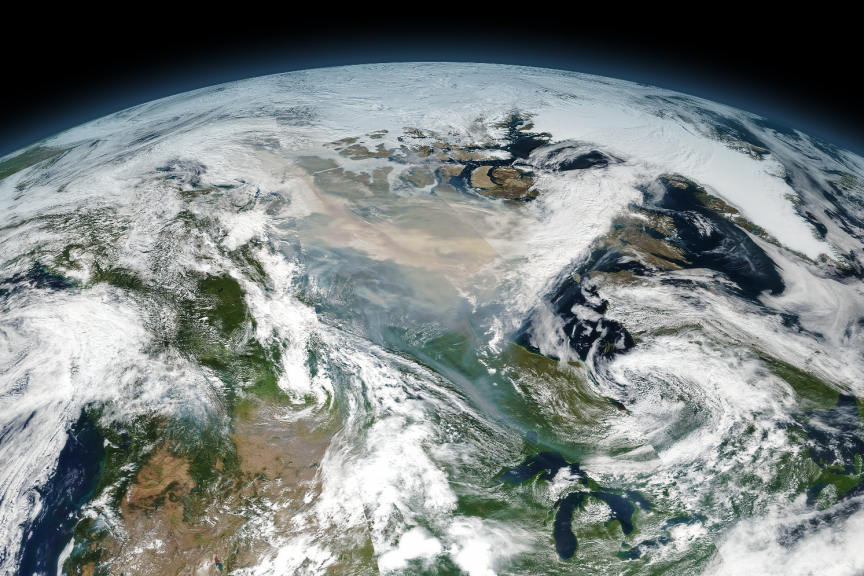

British Columbia wildfires in 2017 created a massive cloud that circled the Northern Hemisphere

Extreme wildfires in British Columbia, Canada, pumped so much smoke into the upper atmosphere in August 2017 that an enormous cloud circled most of the Northern Hemisphere – a finding in the journal Science that will help scientists model the climate impacts of nuclear war.

The pyrocumulonimbus (pyroCb) cloud – the largest of its kind ever observed – was quickly dubbed “the mother of all pyroCbs.” When the smoke reached the lower stratosphere, it was heated by sunlight and “self-lofted” from 7 to 14 miles up within two months. The pivotal ingredient was black carbon (soot), which absorbed solar radiation, heating the air and fueling the smoke’s rapid rise. The smoke lasted more than eight months because the stratosphere has no rain to wash it out.

“This process of injecting soot into the stratosphere and seeing it extend its lifetime by self-lofting, was previously modeled as a consequence of nuclear winter in the case of an all-out war between the United States and Russia, in which smoke from burning cities would change the global climate,” said co-author Alan Robock, a distinguished professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at Rutgers University–New Brunswick.

“Even a relatively small nuclear war between India and Pakistan could cause climate change unprecedented in recorded human history and global food crises,” said Robock, who works in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences.

The scientists used a state-of-the art climate model from the National Center for Atmospheric Research to model the lofting and movement of the colossal Canadian wildfire smoke cloud. The modeling considered smoke characteristics such as the ratio of soot to other ingredients and the rate at which ozone in the upper atmosphere broke down the smoke.

The smoke cloud contained only about 0.3 million tons of soot, while a nuclear war between India and Pakistan could produce 15 million tons and a U.S. vs. Russia war could generate 150 million tons. Still, the scientists validated their previous theories and the climate model they’re using for ongoing research on nuclear war impacts by studying the wildfire, according to Robock.

The observed rapid rise of the smoke plume, its spread and photochemical reactions in the ozone layer provide new insights into the potential global climate impacts from nuclear war, the study says.

The next steps, as part of a Rutgers nuclear conflict climate modeling project, are to use refined nuclear war scenarios to determine the potential impact on the climate and food production on land and in the ocean, along with the potential for global famine. What the scientists learned from the wildfire modeling will make their new work more accurate and credible.

Study co-authors are from the University of Colorado, Boulder; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; National Center for Atmospheric Research; and Naval Research Laboratory.