Jewish Boxers? Who Knew!

A Rutgers lecturer curates an exhibit that celebrates Jews in the fight game

'Most people, when they think of Jews, will think more of accountants than boxers. It turns traditional stereotypes on their head.'– Eddy Portnoy

Ethnic stereotypes being what they are, it is unlikely that anyone playing word association would match “boxer” or “wrestler” with the word “Jew.” Wikipedia lists a grand total of 10 who are now active as professionals. But in the first half of the 20th century, Jewish athletes who made their living in the ring were common – and they are celebrated in an exhibition called Yiddish Fight Club, curated by Eddy Portnoy, who in 2008 began teaching “Elementary Modern Yiddish” in Rutgers’ Department of Jewish Studies.

“One statistic I have heard is that one third of professional boxers in the U.S. during the 1920s and ‘30s were Jewish,” says Portnoy, also an academic adviser at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City, where the exhibit is on display through September 1.

“Boxing tends to be a working class sport and typically works with waves of immigration. Jews came en masse to the United States and began participating in these kinds of pursuits. It’s very similar to many of today’s striving Latino immigrants.”

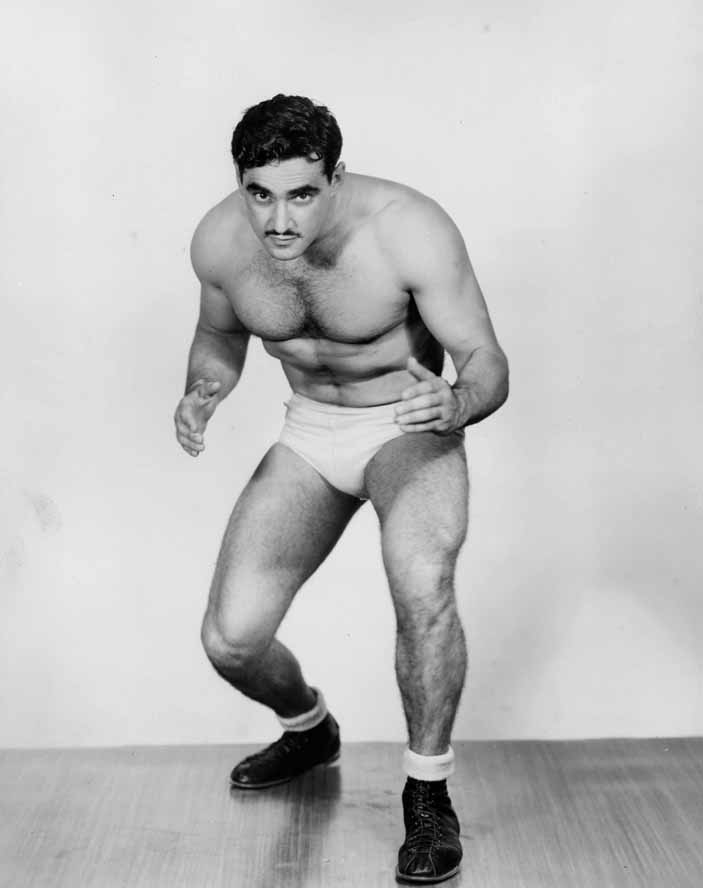

Portnoy’s featured fighters include Rafael Halperin, who was called the “Rassling Rabbi” and famously would not wrestle on the Sabbath. Halperin – who studied for the rabbinate in pre-Israel Palestine while dedicating himself to bodybuilding – apparently was discovered by an American tourist who convinced him he could make money wrestling in the States. He later returned to Israel where he used his wrestling fame to become a prosperous entrepreneur.

As a group, says Portnoy, “there’s a lot of depth to these figures. They often have these fascinating backstories.” Not to mention ear-catching names like “Blimp” Levy and “Kingfish” Levinsky.

In fact, Portnoy says, “during the ‘20s and ‘30s it was so popular to be a Jewish boxer or wrestler that some people who were not Jewish took on that mantle.” Max Baer was one of them. “He wasn’t raised Jewish, but I think he had a Jewish grandfather. Still, Baer put a Star of David on his trunks and boxed as a Jew. A wrestler used the name Dave Levin. It was known that he was not Jewish but was simply capitalizing on the fact that there were a lot of Jewish wrestling fans.”

Intriguing as these characters are, Portnoy says the exhibition is actually inspired by Yiddish, the language that so many Jewish immigrants spoke – which combines a Jewish variant of medieval German with Hebrew and Slavic languages. Portnoy has long been drawn to the vivid Yiddish terms that described boxing and wrestling.

“A shtaysl is an uppercut,” Portnoy says with glee. “That is something you would see in boxing reports in the Yiddish press. Aroysnemen a mashkante, literally to take out a mortgage on someone, was to hold them down and beat them.” A knak (pronounced ka-NOCK’) is a powerful punch.

In Yiddish classes he has taught at Rutgers, as well as his courses on Jewish literature, society and culture, Portnoy has liberally sprinkled these terms in. “One of the things that make teaching language fun and interesting is teaching these little fighting terms and having students create dialogs with them.”

"You could have a simple insult like, 'Shlog zikh dem kop in vant – go hit your head against the wall.' Someone in class may come back with, 'Ikh'l dir gebn a lempl.' A lempl is where you squeeze someone's nose until it turns red."

It is a style of speech that went beyond sport. Portnoy is quick to remind people that gangsters were a fact of life in crowded immigrant Jewish neighborhoods. The colorful language in the exhibition was used at least as often to describe street fights as to chronicle boxing and wrestling.

Keeping history alive

Portnoy makes a point of telling his Rutgers students – several of whom have traveled to New York and seen Yiddish Fight Club – that for many people this slice of the Jewish American experience has largely slipped from memory. “The lives of today’s Jews are mostly middle class and suburban, and most people, when they think of Jews, will think more of accountants than boxers.” But not all. Portnoy says he takes great pleasure when someone emails, or walks up to him at the exhibit, with recollections of ancestors who were fighters.

“It turns traditional stereotypes on their head,” says Portnoy, who – through both his teaching and this exhibit – is doing what he can to keep the memories alive.

The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research was founded in Vilna, Poland, in 1925, and relocated to New York City in 1940 with the mission to study the thousand-year history of Jewish life in Eastern Europe and Russia in all its aspects: language, history, religion, folkways and material culture. The exhibition runs through September 1 at the institute located at 15 West 16th Street.

Journalists are invited to contact Rob Forman of Rutgers Media Relations at formanra@rci.rutgers.edu