First Women Marching Band Members to Be Honored During Rutgers Football Game

The marching band members will be honored during a celebration to mark the 50th anniversary of Title IX

When Jaki Fesq arrived at Douglass College in the fall of 1970, she was ready to march.

Fesq, who earned her undergraduate degree in 1974, grew up watching college football games on TV with her dad. She recalls being dazzled by the geometric shapes the marching bands formed at halftime, and she was determined to make her own mark on the field.

Fesq traded accordion and viola lessons for training on a band-friendly instrument, began marching as a flutist in seventh grade and continued on the piccolo all the way through high school in Pennsauken, NJ.

She arrived in New Brunswick fully intending to join the marching band. “But no: I was told the marching band was men only. I could not believe it,” Fesq said.

For two years, Fesq says, she avoided attending Rutgers football games altogether “because it was too painful to see the band on the field.” Instead, she joined the Rutgers University Wind Ensemble, performing alongside her male counterparts, many of whom also spent plenty of Saturdays each fall suiting up and traveling with the Rutgers Marching 100.

Then, on June 23, 1972, Title IX passed. The civil rights legislation, part of that year’s Education Amendments, not only prohibited gender- and sex-based discrimination in sports programs but also applied to all education programs and activities that received federal financial assistance, including marching bands.

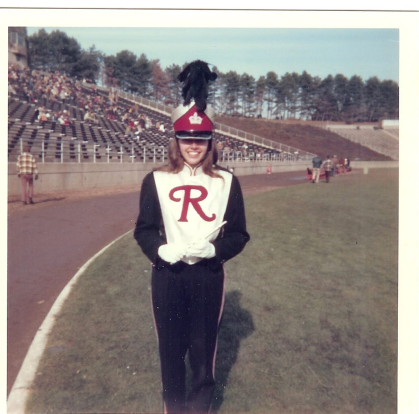

On September 23, 1972, at a home game against Lehigh University, Fesq, by then a junior mathematics major, stepped onto the field as one of the Rutgers Marching 100. She estimates there were fewer than 20 women in that first cohort.

Now, during halftime at the October 7 football game against the Nebraska Cornhuskers, Fesq and other early women members of the marching band will be honored as part of a celebration of women in athletics. The halftime celebration is part of a series of tributes and programs Rutgers is hosting during the 2022–2023 academic year to mark the 50th anniversary of Title IX.

Fesq and her fellow women marching band members opened the doors for many others at the university, said Julia Baumanis, assistant director of university bands, assistant director of the Marching Scarlet Knights and the director of pep bands.

“I owe a lot of gratitude to those first women who marched and set the path for anyone, regardless of sex, gender identity or sexual orientation, to be a part of the band,'' Baumanis said. "Without them, I do not believe that there would have been a place for me as the first female band director in Rutgers history.”

Now, out of the about 250 members of the marching band, 110 identify as female, Baumanis said.

Integration occurred in fits and starts. Fesq says many male band members griped about their female colleagues, convinced that women couldn’t hack striding down the field in their Big Ten high-step marching style or endure their high-energy pre-game and halftime shows. In addition, Fesq says, women were expected to don uniforms fitted for men’s bodies – performing in drooping sleeves and pant legs, gaping waists and jackets that tended to be snug across the bust. Breaking through the all-male culture and encountering the bawdy tunes erupting on the Rutgers “sing bus” used for away games proved difficult, as well.

Luckily, Fesq says, the women had an ally in then-band director Scott Whitener.

“Scott made a point to stress to everyone that ‘a band member is a band member,’ and no one would be treated differently,” recalls Fesq, who also holds a master’s degree and doctorate in education from Rutgers. “That was great and did a lot to ease the transition.”

Despite the sometimes-bumpy road to acceptance, Fesq says she’s glad she took the field 50 years ago. She even met her future husband, Bruce Haislip, a 1975 graduate of Rutgers College, during her marching band tenure.

Ultimately, Fesq says, “my two years in the marching band were the best of my college career.”