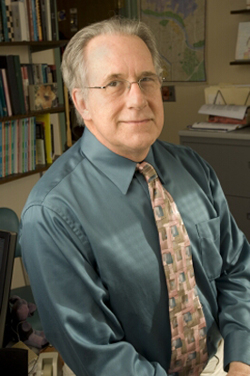

Political scientist Richard Lau believes that voters, like other decision makers, try to do the right thing.

At first blush, the process seems simple: Duck behind a curtain, scan a list of names, press a couple of buttons or pull some small levers, and exit. Voilà, you’ve voted.

For many Americans, the re-emergence from behind the curtain marks the end of their connection to any given election cycle. They probably won’t give much more thought to the candidates – or the act of voting – once the winners and losers are announced.

Richard R. Lau, professor of political science in the School of Arts and Sciences, believes citizens should give more thought to the process. “We started with large Democratic and Republican primary fields running for president in 2008,” he said. “How many of us had the time or inclination to learn everything about all candidates? Yet many of us will still vote, but under conditions of far less than complete information, opening up the very real possibility that many of us will vote incorrectly.”

Lau and fellow political scientist David P. Redlawsk of the University of Iowa explore the process by which voters choose among candidates in How Voters Decide: Information Processing During Election Campaigns (Cambridge University Press, 2006). The book, which received the Alexander George Book Award from the International Society for Political Psychology, is the culmination of a 15-year project that featured 750 participants voting in mock presidential primaries and general elections.

How Voters Decide grew out of a 1981 dissertation by a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon, where Lau first taught. “The student was using a traditional bulletin board with large note cards to see where candidates stood on the issues as a way to study decision making. It’s a technique often used in business schools,” Lau explained.

With National Science Foundation funding, Lau and Redlawsk, then a Rutgers doctoral degree candidate, set about to study how voters made their choices. They created composite candidates using personal traits and policy positions of real-world politicians whose ideologies spanned the political spectrum. Additionally, they manipulated the size and composition of primary fields.

To gain a view of the voting mindset, the researchers employed a computer-based methodology – think of a scrolling Jeopardy! game board on a computer screen – allowing “voters” to choose personal and political information boxes about candidates during a fixed time period. Voters self-selected topics from among the randomly scrolling boxes to the exclusion of others. Presumably, their ultimate choice was influenced by their information gathering, among other variables.

The researchers classified voters by information gathering strategies into four groups, with perhaps the rarest being the voter who engages in dispassionate rational choice. He or she actively seeks as much information as possible about each candidate’s experience and policy proposals and evaluates the likely consequences on her- or himself and family.

A second group also is likely to learn much about competing candidates, but their information gathering and perceptions are often biased in a predetermined direction (confirmatory decision making) by early socialization. “My parents are Republicans, and so am I,” these voters say. For others, efficiency – “fast and frugal” decision making – is the benchmark. They actively seek out only a very few of the candidates’ attributes and ignore everything else. Think of these voters as applying a litmus test to a candidacy, such as favoring or opposing abortion.

A fourth group is marked by “bounded rationality” and intuitive decision making. These voters require less information and use heuristics, or cognitive shortcuts, such as stereotypes (“Democrats are for the working man”), to reach decisions. For them, making easy, “good enough” decisions trumps making the best possible choice most of the time.

As Lau observes, voters do not collect information in a vacuum. They bring personal histories, political interests, and sophistication to the process. They also vary in their cognitive limitations, or how much information they can absorb and use effectively to reach decisions.

“Voters are bombarded with information throughout political campaigns, and some issues take precedence at a given moment,” Lau said. “When multiple candidates hold similar views on issues deemed important by voters, the difficulty in choosing ‘correctly’ increases.”

To determine the “correctness” of their choices in select mock elections, voters were given a second task: to review briefing books on two candidates, the one for whom they voted and another. In a four-candidate primary, the computer selected a hopeful whose views closely resembled each voter’s choice. Researchers encouraged voters to change their minds, without embarrassment, if additional information warranted a switch.

About 70 percent of the subjects reported they would vote for the same candidate, which Lau considers one measure of voting “correctly.” “Voters, like other decision makers, try to do the right thing,” he said. “Voting is about information, and thus, understanding how people acquire and use information in making vote decisions is critical.”