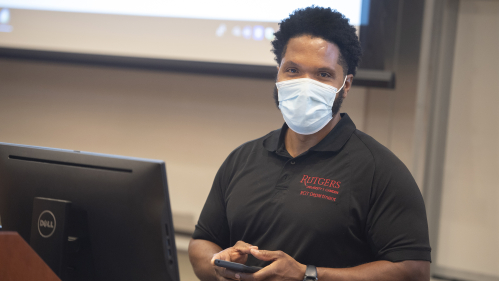

Remoan Headen, an environmental service worker, sanitizes conference rooms at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School with a specialized misting wand.

Stories of Life at Rutgers Through the Pandemic

Essential workers at Rutgers have kept the university running and served others who remained on campus while most of the community has been working remotely since March.

They have maintained the buildings and grounds; kept faculty, staff and students connected online; served the hungry and provided other services. We spent some time talking to the workers about how the pandemic has changed their lives and jobs. Here are their stories.

Making Sure No One Goes Hungry

When in-person instruction at Rutgers ended in March, Deja Little said she never considered abandoning her post at the PantryRUN in the Paul Robeson Campus Center.

“For me, it was a no brainer,” said Little, 20 (pictured right), a rising senior who started as federal work-study student at the food pantry shortly after arriving at Rutgers University-Newark four years ago and became an intern there in January. “We quickly came up with ways to make it safer for all of us. It feels rewarding because this a very hard time for people, and they are so appreciative that we are open and can help.”

Prior to the pandemic, the East Orange resident majoring in social work and minoring in criminal justice worked 10 hours a week crafting social media flyers and organizing work-study student schedules and donation deliveries. Now, with a reduced staff, she works 20 hours a week but in a more hands-on capacity with food pantry coordinator Gina Gohl and a handful of student volunteers to stock shelves and package and distribute bags to reduce the number of people coming in and out of the pantry.

Rutgers-Newark’s food pantry served a little more than 300 people through a self-shopping approach before COVID-19, said the director, Ellen Daley. Currently, an average of 100 people – both staff and students – stop by for a weekly bag of pre-packed necessities.

“Across the country, food insecurity has increased, exacerbated by rising food costs and problems with the food supply chain,” Daley said. “During the same time, we have learned that COVID-19 takes a bigger toll on Black and brown communities, in part because of the sorts of health disparities that are made worse by poor diets. It has remained important that we keep the PantryRUN doors open to support our Rutgers community.”

Gohl, who has worked part-time at the pantry since November, said she is grateful to be able to continue working with others through the quarantine. Though they are not physically passing through the pantry, Gohl and Little said they have enjoyed interacting with the people they serve during weekly pickups.

“We have more moments where we have to work around people’s schedules so people can eat for another week,” Little said. “Even though the pandemic has made it so that you are farther from people, we have been more intimate with people in another way.”

Gohl has grown accustomed to working in an empty campus center, but during those first few days after the campus cleared out, she said the silence was deafening.

“It’s weird being on a college campus and being one of only a handful of people in the whole building,” Gohl said. “I miss the work-study students who come through the pantry, and I miss the vibrancy we used to have on campus.”

– Lisa Intrabartola

Fighting an Invisible Enemy

Before the coronavirus pandemic, Maria Santana and Ana Espinal spent their workdays making sure that the offices at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School – usually occupied by hundreds of students, patients, doctors and staff – were clean and sanitary.

They didn’t give much thought to the role they played in protecting public health through their jobs.

Now they realize their work could prevent someone from contracting COVID-19, and they find themselves worrying not only about their own health but also about the health of those who come into one of the buildings that they clean.

“I feel that we’re cleaning something invisible and it can be frustrating,’’ said Santana, who has worked at the medical school for nine years. “But we continue to do it, because this is not over yet.”

Espinal is also struck by the weight of her responsibilities at work during the pandemic.

“It’s very important for me because at this difficult time I need to stay strong for serving others while protecting myself in this situation,” she said.

The past four months have been lonely and sad the women admit, and both are looking forward to the time when life goes back to normal.

“It’s totally different,” Espinal says. “It is so quiet.”

Santana says she feels like she is working in a ghost town without the people and without the noise she is used to in the building.

“But it’s satisfying for me to know that my department is able to contribute to fixing this dangerous situation, ” she said.

– Robin Lally

Helping Students From Afar

Even though the students are gone, Kasene Logan, who oversees 15 Washington Street -- one of six residence halls at Rutgers University-Newark -- says in some ways his job is still the same. He is there to provide support whether in person or remotely.

‘’There is less face-to-face interaction, but what will remain the same is the consistency in being a resource to the students for whatever they need,’’ Logan said.

When students moved out in March, Logan kept in touch with them mostly through email. He sent them information about the food pantry and other services that were available to help students whose lives were directly impacted by the pandemic, whether through job loss or illness.

He remained busy but he missed the in-person interaction.

“You get used to seeing so many students traveling back and forth to classes and occupying the study lounges in the building, and now it is like living in a ghost town with little population,’’ he said. “It doesn’t feel as lively as it did prior to COVID-19. You can tell the effects of COVID-19 have tremendously changed the atmosphere of the campus and the Newark community.’’

But Logan, like so many other around the university, is starting to see some opportunities for innovation in the way they do their jobs. In Logan’s case, is means continuing to provide programming for students even though they are not living on campus.

He is developing digital programs that include group DIY projects, Netflix parties to bring students together to watch documentaries and films and discuss relevant topics.

“My job is to continue to be supportive and advocate building a positive community within the residence halls,’’ Logan said. “Even though we are looking to conduct programming digitally to continue to comply with the New Jersey state and federal policies put in place, we still want our students to know their well-being is important to us and we will continue to make our communities positive educational environments while following these policies in place to keep them safe as well.’’

What strikes Logan in this moment is how the essentials in life have changed.

“You know the statement 'phone, wallet and keys' before you always leave home in the morning?’’ Logan asked. “Well now it is, 'phone, wallet, keys and mask.' The mask has truly become an essential item to leave home with.’’

– Andrea Alexander

Life at Rutgers Farm

The workers at Rutgers Farm are used to being on campus when most others are gone.

“I’m responsible for animals,’’ said Felicia McCloskey, a senior research animal worker who oversees care and breeding of the pigs on the farm. “That means whether there is a natural disaster or a global pandemic someone has to be here. It gives me a sense of pride to know how essential my job really is."

The team of nine full-time support staff members who manage the herds on the Cook campus including the cattle, goats and sheep on the farm at Rutgers University-New Brunswick have worked through blizzards and hurricanes that have shut down the university. But this time they had to adjust in more sustained ways.

“At first, being on campus was not much different from a normal winter break, but as time went you could really see the change in the environment,’’ McCloskey said. “Everyone was asked to work from home if their position allowed for it. That made the campus very quiet and at times eerie. I miss seeing the students on campus and the energy they bring.’’

Students usually play a critical role on the farm. Student workers assist with the care of animals. They help socialize the new animals when they are born to help them get used to visitors. The farm staff also teaches classes for animal sciences majors in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences to give them hands-on experience.

This spring the staff found ways to adjust their teaching. Rebecca Potosky, a senior research animal care tech who oversees care of the sheep and goats and the chicken flock, used her camera phone to record and share moments the students were missing.

“I was able to capture a goat giving birth, some treatments, and other routine procedures to share,’’ Potosky said.

“I feel thankful that in this time of uncertainty and so much loss, I am able to continue to work,’’ she said. “I also recognize the importance of my job. Animals need to be fed, cleaned, and taken care of regardless of the situation. Our program provides students with animals for hands-on teaching opportunities that are essential to their future careers, and I am dedicated and proud to continue providing care.’’

Kelly Vuong, a senior research animal worker who manages cattle on the farm, was also able to capture of the birth of a calf on her camera phone to share with students. If it had been normal times, Vuong would have missed it because the cow gave birth over the weekend, when she usually is not at work.

For many of the workers on the farm, the uncertainty that hung over the last day of classes in March is a memory they will never forget.

“I tried to remain calm and reassuring for the students, but it was difficult, especially for the seniors who were so distraught not knowing whether this would be their last day on campus as an undergrad or not. To many students, the farm is an escape, almost a sanctuary, and having that taken away from them was very sad.’’

– Andrea Alexander

A Scene from The Twilight Zone

Emily Reid, a supervisor for environmental quality control for Institutional Planning and Operations in Newark, is praying that life gets back to normal and the coronavirus disappears.

But until it does, she will continue to spend time in empty classrooms, doctors' offices, laboratories and the library at New Jersey Medical School making sure everything is wiped down with disinfectant, floors are mopped and hand sanitizer dispensers are filled. She and her colleagues are on the front line every day working to protect others from COVID-19.

“Before this, I would see students going to class, doctors going to the operating room and staff members starting their day,” Reid said.

Now she describes the same area as deserted. “It’s like a scene out of a Twilight Zone movie,” Reid said.

The mother of three grown children and grandmother of two spends her days fighting this invisible virus by keeping surfaces as clean as she can. When she goes home, she does it all over again, cleaning all the surfaces to keep everyone safe.

“I purchased masks, gloves and hand sanitizer for my family and make sure that everyone is practicing social distancing,” Reid said. “We go to work, the supermarket, the drugstore and the doctor’s office. Other than that, we are in the house until this pandemic is over.”

– Robin Lally

Keeping the Community Connected

When Rutgers University-Camden shifted to remote learning, the Information Technology department kicked into high gear to distribute loaner notebooks and field calls to help faculty, staff and students settle into working from home.

But after assisting the community with the transition, the staff started to realize the stark difference on campus.

“It wasn’t long till the lack of everyday noise and movement started to sink in and you realize the magnitude of the situation,’’ said Victor Gomes, a system administrator. “In short, most days feel as if reality has taken a vacation.’’

Pierre A. Cadas, assistant director of information technology, misses the interaction he had with the community.

“It feels surreal,’’ Cadas said. “The campus is usually a vibrant community pulsating throughout the day with activities and people just hanging out. To experience the absence due to COVID- 19 is absolutely something unimaginable, something no one saw coming.’’

But the IT staff goes to work with a sense of purpose, knowing their job is critical at this time.

“During this time more than ever, it is important to our users that their remote transitions and transactions run near to seamless,’’ Cadas said. “We are providing a valuable and meaningful service to the campus community.’’

Being able to go to work every day has been a comfort, Gomes said. He has spent the summer with others in the IT department upgrading microphones in classrooms to prepare for when students return.

“To be able to continue to provide for my family at this time means the world,’’ Gomes said. “Being able to maintain some form of schedule at work has allowed me and my family to deal with the current situation with some sense of normalcy.’’

– Andrea Alexander

A Job Transformed

As a civilian security officer with the Rutgers University Police Department (RUPD), Andrew Santos always thought of himself as the eyes and ears of the police.

He attended football, basketball games, concerts and social gatherings to make sure that everything was running smoothly and there were no security problems.

He liked being surrounded by the thousands of people on the thriving Rutgers-New Brunswick campus who were going about their daily routines. He never imagined how quickly it could all change.

“You rarely see anyone anymore and there are no sports events or concerts,” he says. “Before COVID-19 the campus was very lively with lots of foot and vehicle traffic, everyone was outside just having a good time.“

Today, instead of providing after-hour escorts for students, faculty and staff, patrolling the campuses, performing building security inspections and issuing parking citations, Santos’ job revolves mostly around enforcing social distancing requirements and the rules instituted since the coronavirus pandemic transformed university life.

His main goal over the past five months: making sure each day that those still on the “deserted” New Brunswick campus are staying six feet apart and wearing masks. Even his interactions with coworkers are limited. Instead of receiving daily assignments at in-person briefings like it used to be before the shutdown, now assignments are delivered via text message.

“Its a complete ghost town,” says Santos who spends much of his time zipping around campus on a Segway, a three-wheeled motorized electric vehicle, making sure there were no safety issues. “It’s definitely strange. The few people you see walking around are all wearing masks, it’s like we’re all in a movie. I would have never thought something like this would ever happen.”

Santos says besides missing the robust activity on the New Brunswick campus, he finds himself looking back on some of the daily routines that he took for granted before the pandemic – like his stop at 16 Handles, the frozen yogurt and ice cream shop on the Livingston campus.

“Honestly, I miss walking into 16 handles and being able to pour my own choice of frozen yogurt into a bowl, and then adding as many toppings as I want,” Santos says. “Now you’re not allowed in the store unless you’re picking up a prepaid order, that someone else makes for you, it’s just not the same.”

– Robin Lally