Climate Change Is a Major Concern for Rutgers Senior

Honors student Lauren Rodgers loves chemical oceanography and wants to earn a doctorate

'Lauren is just what you want in a scientist: clear-eyed and thoughtful. You have to be determined. The very mundane stuff that you have to do to generate data is at times tedious.... Lauren has the determination and perseverance to do that kind of tedious work to make the data happen, and then she has the insight to see what it means and to understand the relevance.' – Professor Elisabeth Sikes

Rutgers senior Lauren Rodgers once dreamed of becoming a fiction writer. But then she enrolled in a high school science and math program in her native Columbia, South Carolina, where she read an article that discussed the ocean’s critical role in absorbing carbon dioxide, the major greenhouse gas linked to global warming.

“That totally changed my perspective on everything,” said Rodgers, a member of the Class of 2019 and student at the Rutgers–New Brunswick Honors College. “It was like, oh my gosh, that’s so amazing. I had never heard of any correlation between the climate and the ocean before, so I started gearing my research toward that.”

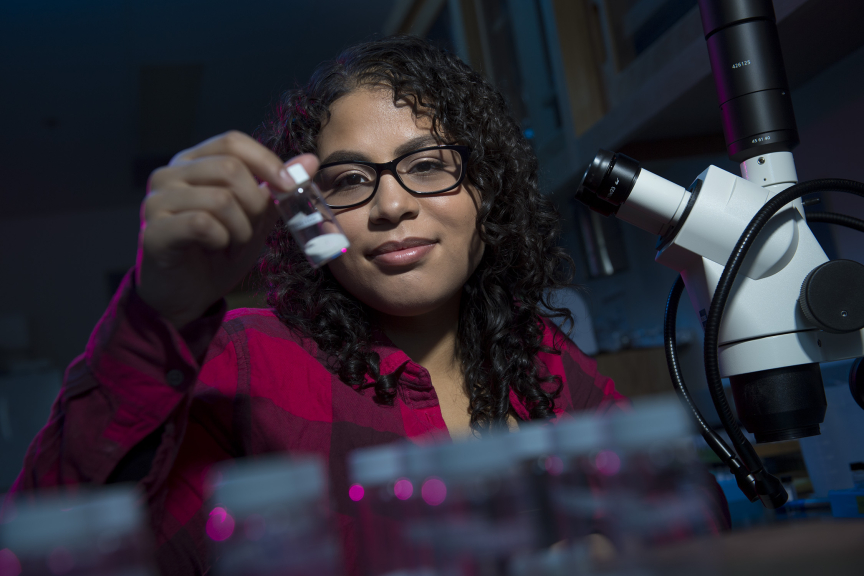

Today, Rodgers is conducting climate change-related research as she completes her undergraduate degree in chemical oceanography. She is a George H. Cook Scholar in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences, and her honors thesis involves helping to assess sea surface temperatures over the last 150,000 years in the Southern Ocean near Tasmania. This year, she earned the Outstanding Senior Award in the Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences.

“Climate change is one of the biggest issues right now,” said Rodgers, who is 22. “Organisms are dying off and going through mass extinctions. The climate is completely changing and you can see it all around us. It’s not something you can ignore. We are causing it and we can make changes to lessen the impact, but at this point we cannot prevent it. Many people in power don’t seem to have climate change on their agenda, which is really disappointing.”

Elisabeth L. Sikes, a paleoceanographer and professor in the Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences, has mentored Rodgers during two research projects on sea surface temperatures and thinks she has a bright future.

“Lauren is just what you want in a scientist: clear-eyed and thoughtful,” Sikes said. “You have to be determined. The very mundane stuff that you have to do to generate data is at times tedious. You’re doing the same thing over and over and over again. Lauren has the determination and perseverance to do that kind of tedious work to make the data happen, and then she has the insight to see what it means and to understand the relevance.”

Rodgers is also unassuming, level-headed and dedicated, Sikes added.

“She has this fearlessness to just go ahead and do it and get out of her comfort zone, so I think that speaks well for her future. She is a really remarkable young woman and I really enjoyed having her in my lab.”

With guidance from Sikes this winter and spring, Rodgers has been analyzing sediment samples from the Southern Ocean in Nathalie Goodkin’s lab at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. She’s been crushing, cleaning and analyzing tiny shells that sink to the ocean bottom. These fossils can shed light on the past. The shells indirectly reveal sea surface temperatures over the eons through the ratio between the magnesium and calcium in their carbonate skeletons.

“Sea surface temperature is important because it has a direct relationship to climate,” Rodgers said. “If the surface of the ocean is warmer, that tells you the Earth is warming.”

A warming ocean adds to sea-level rise, increasing the risk of coastal flooding in New Jersey and elsewhere.

Rodgers, who loves reading, soccer, trying different foods and baking, plans to take a break after graduation and find some lab work to gain more experience. Then she wants to earn a master’s degree and a doctorate.

“I definitely love climate science and want to do that in the future,” she said. “I would like to have my own lab and conduct research. I really want to help people understand climate change better and help them with solutions.”