Unmarried, non-college graduates at particular risk

NEW BRUNSWICK, N.J. – The suicide rate for middle-aged people – a group considered relatively protected from suicide and with historically stable suicide rates – took a sharp upward jump between 1999 and 2005, according to a new study by sociologists Julie Phillips of Rutgers University and Ellen Idler of Emory University. Click here to read about the research on Emory's eScienceCommons blog.Their study has been published in the September/October issue of the journal Public Health Reports.

Phillips and Idler relied on data from the National Center for Health Statistics and the United States Census Bureau in their research. They were joined by two co-authors, Ashley Robin, an undergraduate at Vanderbilt University at the time of the research, and Colleen Nugent, a graduate student at Rutgers. Robin was participating in Project L/EARN, a Rutgers summer program for promising undergraduates, at the time of the research.

Among their key findings:

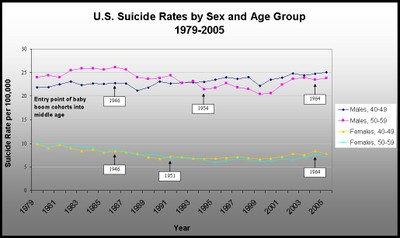

- There was a substantial increase in the suicide rate for men (50-59) and women (40-59) between 1999 and 2005. For men aged 40 to 49, the increase began about a decade earlier, in the late 1980s.

- Increases in middle-aged suicide rates were typically greater among those who were unmarried.

- The rise in suicide was particularly dramatic for people without college degrees, with increases near 30 percent.

- People with college degrees seem to have escaped the trend.

Traditionally, U.S. suicide rates rise in adolescence and again in old age. They stabilize in maturity and middle age, a time when people are invested in their families and work. For men in particular, suicide rates rise again in old age, when children are grown, illness is more frequent and spouses and contemporaries start to die.

Phillips and Idler note that although Baby Boomers – those born between 1946 and 1964 -- had a higher than usual suicide rate as adolescents, they followed the usual pattern in maturity. In fact, the suicide rate in general declined steadily in the United States for several decades before 2000.

Beginning in 1999, however, the rates rise dramatically for middle-aged people and, in particular, for people born during the 1950s, breaking the decades-long trend. What happened?

Phillips and Idler think that both “period” and “cohort” effects are at work.

Boomers had high suicide rates as adolescents and have been noted for their relatively high rates of substance abuse, the researchers report. Furthermore, among boomers, the onset of chronic health problems in middle age and the associated financial burden may have struck particularly hard, given boomers’ unprecedentedly high levels of life expectancy and overall health. But problems particular to Baby Boomers aren’t enough to explain the dramatic rise in rates after 1999, Phillips and Idler write. They speculate that economic pressures, particularly for people without college educations, intensified in those years, and thus put many middle-aged people, particularly unmarried, non-college-educated men, at greater risk.

“If these trends continue, they are cause for concern,” they wrote. “Male baby boomers have yet to reach old age, the period in the male life course at highest risk for suicide; if they continue to set historically high suicide rates as they did in adolescence and now in middle age, their rates in old age could be very high indeed.”

Phillips said that a comprehensive study for the first decade of the new century won’t be possible until 2013 but that preliminary data for the years 2006 and 2007 shows the trends continuing.

Media Contact: Ken Branson

732-932-7084, ext. 633

E-mail: kbranson@ur.rutgers.edu